Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

The sky over the Thames was the colour of a day-old bruise. London’s default setting. A man in a wool coat paused at a corner, waiting for a black motorcar to pass. He lifted his wrist — a gesture still new, a quiet rebellion against the pocket-and-chain his father swore by.

His gaze followed where he expected the time to reside. The watch was a modern manifesto, blued-steel hands, porcelain dial, silver case catching the kind of light only London would dare call daylight. He admired it for a moment, the steady march of the small seconds hand a tiny orchestra that obeyed him alone.

Then came the first drop of rain, not so much a warning, more an accusation. Cold, pointed, and personal. The city immediately shifted gear. Umbrellas erupted like mushrooms, shoes began their synchronised splashing, and the air filled with the hiss of tyres and mild British regret.

His hand didn’t fly to his hat, but to his wrist. A flash of panic. He pulled his cuff down over the watch like a fire curtain, shielding it with the urgency one usually reserves for a newborn or a tax document.

Safe beneath the tobacconist’s awning, he ignored the wet coat. The real emergency was ticking quietly under his sleeve. He eased back the damp fabric with the care of a bomb disposal expert. The crystal was fogged. He wiped it, held his breath, and pressed the watch to his ear.

A heartbeat. Still there.

He exhaled. Experiencing the kind of relief only available to people who’ve saved something that never needed saving. The wristwatch, hero of the trenches and darling of the new age, had met its natural enemy, water. Its kingdom was made of glass, and the sky refused to cooperate.

The Race for Breath

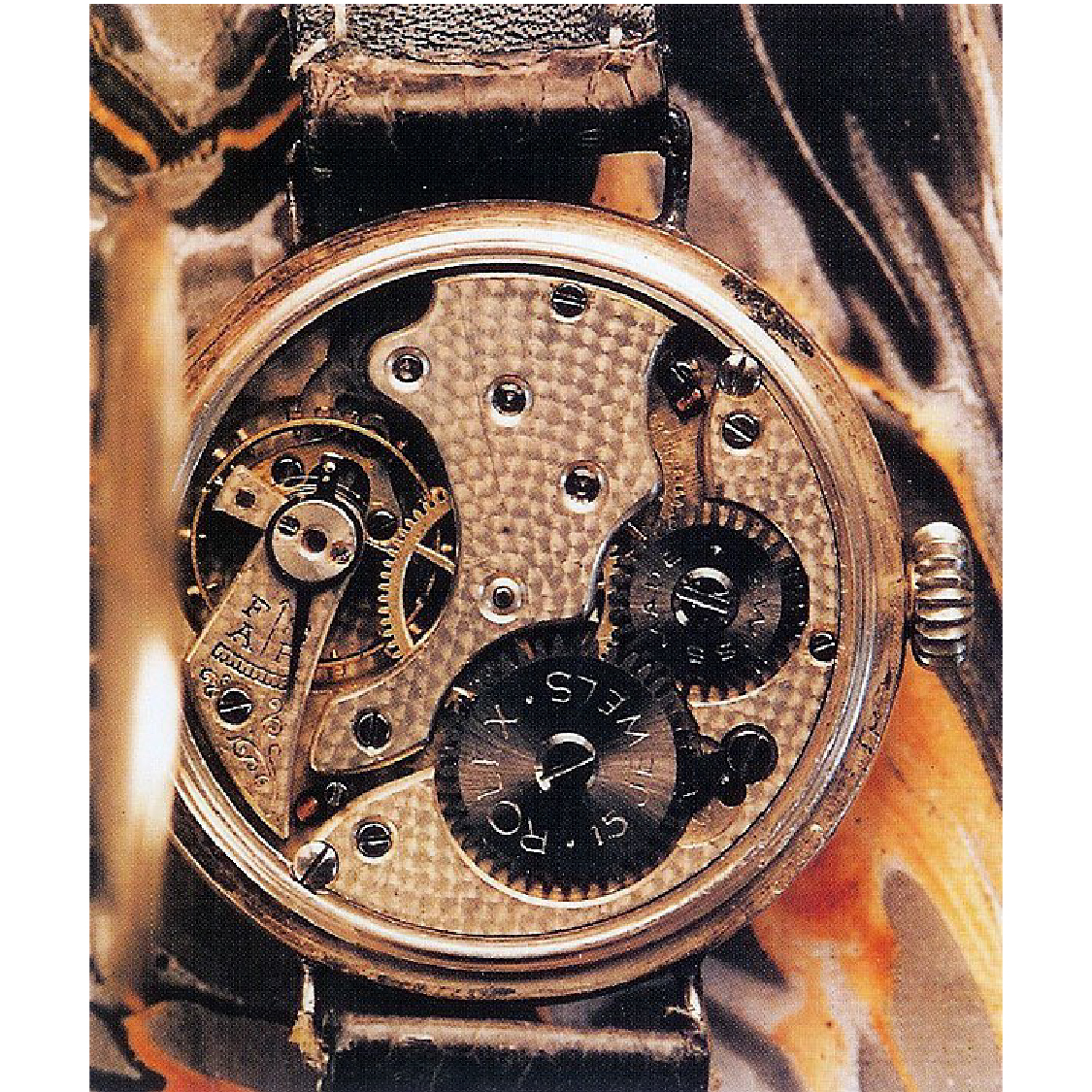

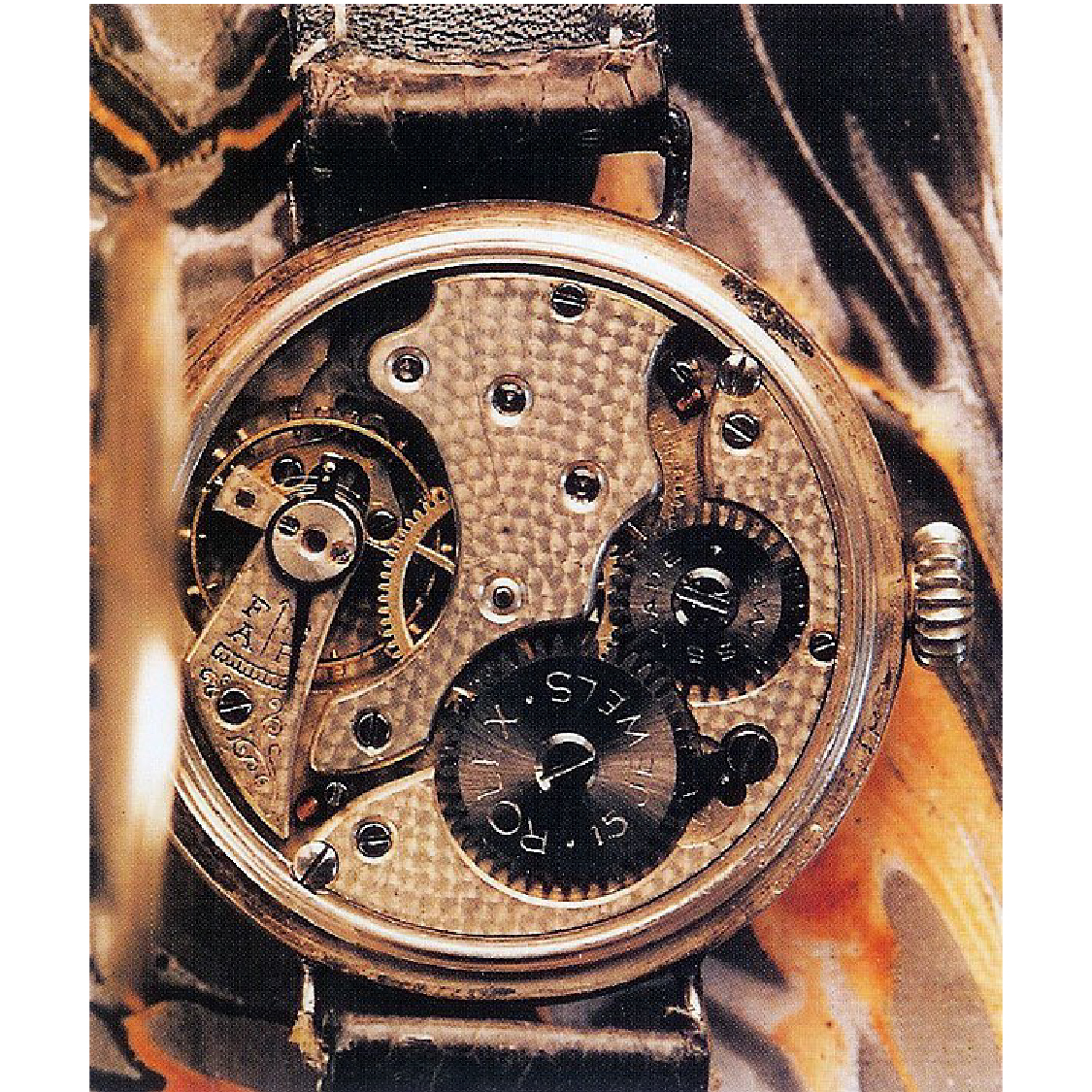

For all its newfound prestige, the wristwatch was still a delicate creature. In essence, it was still a pocket watch that had decided to go outside without a jacket. This problem obsessed both the men who wore them and the men who made them. In Swiss workshops, where brass filings and oil hung in the air like incense, a question echoed again and again. How do you make something both beautiful and watertight without turning it into a plumbing fixture?

A watch case was a miniature fortress, but one riddled with weak spots. The bezel could leak, the caseback could crack, and the crown — the traitor’s gate — had to open every day just to keep the thing alive.

Early attempts were, for the want of a better word, enthusiastic. Some makers fitted inner dust covers called ‘cuvettes’, which were basically polite requests for the elements to stay out. Others went medieval, snapping one shell over another to create the ‘clamshell’ case, a name that suggested elegance but delivered blisters. Gaskets were made of cork, lead, or leather, materials that aged about as well as optimism. And the screw-on crown caps, while ingenious, had a habit of disappearing faster than a promise at a board meeting.

They worked. Briefly. But each fix was essentially a polite attempt at denial, a plea to keep moisture and dust at bay with manners alone. The great unanswered question remained, well, unanswered: how to make a watch that could face a storm without looking like it came from a plumbing aisle at Harrods.

Because what the watchmakers were really chasing wasn’t just a seal, but dignity. They wanted the wristwatch to keep its poise while the weather lost its temper. To hold time, not clutch it. Somewhere between brass filings and mountain fog, they weren’t just designing a case. They were trying to teach civility to swim.

The Oyster and the Channel

The English Channel in October is less a body of water and more a particularly vindictive slab of granite. On the morning of October 7, 1927, it was busy trying to freeze the willpower out of Mercedes Gleitze, a London stenographer attempting to swim across it. A career move her colleagues likely considered ‘imaginative.’

Around her neck, ribbon strapped above the relentless chop, was a small steel contraption. An object designed for soirées and polite glances, now doing its best impression of a submarine.

The watch was there because Hans Wilsdorf, founder of Rolex, had solved the great riddle, and wasn’t about to let modesty ruin the announcement. His answer to the problem of water and dust was the 1926 Oyster case, a marvel of hermetic engineering. Its bezel, caseback, and crown all screwed down to form an impenetrable vault, protecting the delicate movement within.

But invention alone was not enough. Proof was the currency of belief. Wilsdorf needed a bigger stage, and nothing got bigger than the English Channel, attempting to drown the star that would be Mercedes Gleitze.

For more than ten hours, she battled the waves and the creeping, brutal cold. The tide and the temperature were against her. When Gleitze was finally pulled from the water, exhausted but triumphant, the small Oyster was not just surviving; it was keeping perfect time. The water had failed to breach its walls.

Wilsdorf, never one to waste a miracle, took out a full-page ad on the front of the Daily Mail, declaring “The Triumph of the Rolex Oyster.” It wasn’t just a technical win, but a marketing masterstroke. The watch had held its breath, and the world applauded its lungs.

The Age of the Tool (Watch)

That advertisement in the Daily Mail did more than sell a watch. It reversed an age-old anxiety. The wristwatch, once a delicate trinket, was no longer the thing to protect; it was the thing that protected you.

Thus began the quiet arms race of endurance. Waterproofing was no longer a novelty but a calling and would very, very soon be a given. Across Switzerland, cases thickened, crowns tightened, and balance wheels marched on behind glass that refused to mist. Watchmakers began to imagine their creations not as ornaments, but as instruments.

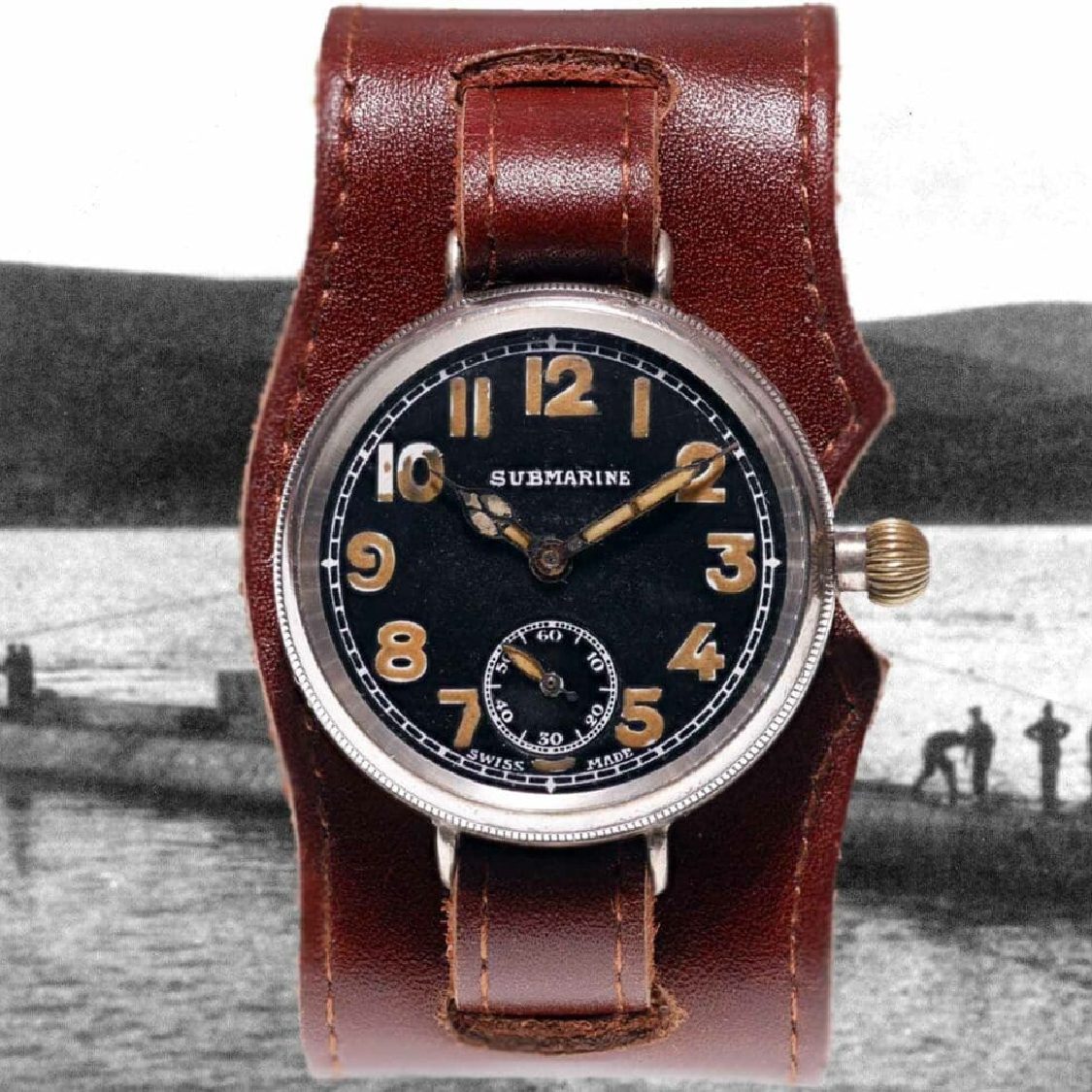

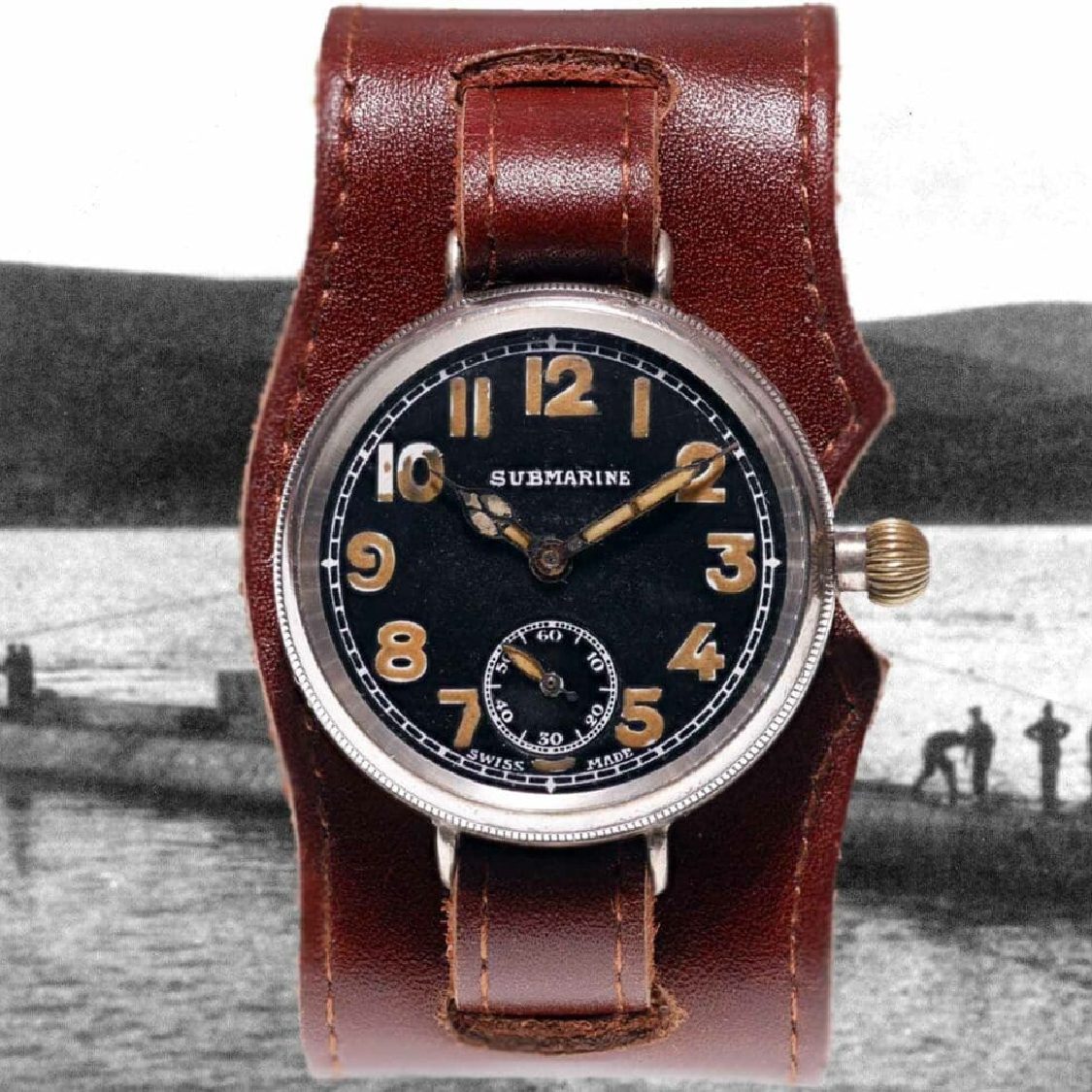

By the late 1930s, this new faith in fortitude had become a language of its own. Mountaineers needed watches that could withstand extreme temperatures and altitudes; engineers wanted ones that wouldn’t flinch at oil or dust. And in the hidden docks of Italy, Panerai was quietly building instruments meant to be read in the black silence of the sea.

These were not yet the tool watches the world would come to know, but their blueprints.

The watch had stopped fearing the elements and begun to negotiate with them. The migration was nearly complete. Time had shifted from pocket to wrist, from a fragile accessory to faithful accomplice. But a final transformation still waited below the surface, where water pressure was measured not in raindrops, but in fathoms.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

The sky over the Thames was the colour of a day-old bruise. London’s default setting. A man in a wool coat paused at a corner, waiting for a black motorcar to pass. He lifted his wrist — a gesture still new, a quiet rebellion against the pocket-and-chain his father swore by.

His gaze followed where he expected the time to reside. The watch was a modern manifesto, blued-steel hands, porcelain dial, silver case catching the kind of light only London would dare call daylight. He admired it for a moment, the steady march of the small seconds hand a tiny orchestra that obeyed him alone.

Then came the first drop of rain, not so much a warning, more an accusation. Cold, pointed, and personal. The city immediately shifted gear. Umbrellas erupted like mushrooms, shoes began their synchronised splashing, and the air filled with the hiss of tyres and mild British regret.

His hand didn’t fly to his hat, but to his wrist. A flash of panic. He pulled his cuff down over the watch like a fire curtain, shielding it with the urgency one usually reserves for a newborn or a tax document.

Safe beneath the tobacconist’s awning, he ignored the wet coat. The real emergency was ticking quietly under his sleeve. He eased back the damp fabric with the care of a bomb disposal expert. The crystal was fogged. He wiped it, held his breath, and pressed the watch to his ear.

A heartbeat. Still there.

He exhaled. Experiencing the kind of relief only available to people who’ve saved something that never needed saving. The wristwatch, hero of the trenches and darling of the new age, had met its natural enemy, water. Its kingdom was made of glass, and the sky refused to cooperate.

The Race for Breath

For all its newfound prestige, the wristwatch was still a delicate creature. In essence, it was still a pocket watch that had decided to go outside without a jacket. This problem obsessed both the men who wore them and the men who made them. In Swiss workshops, where brass filings and oil hung in the air like incense, a question echoed again and again. How do you make something both beautiful and watertight without turning it into a plumbing fixture?

A watch case was a miniature fortress, but one riddled with weak spots. The bezel could leak, the caseback could crack, and the crown — the traitor’s gate — had to open every day just to keep the thing alive.

Early attempts were, for the want of a better word, enthusiastic. Some makers fitted inner dust covers called ‘cuvettes’, which were basically polite requests for the elements to stay out. Others went medieval, snapping one shell over another to create the ‘clamshell’ case, a name that suggested elegance but delivered blisters. Gaskets were made of cork, lead, or leather, materials that aged about as well as optimism. And the screw-on crown caps, while ingenious, had a habit of disappearing faster than a promise at a board meeting.

They worked. Briefly. But each fix was essentially a polite attempt at denial, a plea to keep moisture and dust at bay with manners alone. The great unanswered question remained, well, unanswered: how to make a watch that could face a storm without looking like it came from a plumbing aisle at Harrods.

Because what the watchmakers were really chasing wasn’t just a seal, but dignity. They wanted the wristwatch to keep its poise while the weather lost its temper. To hold time, not clutch it. Somewhere between brass filings and mountain fog, they weren’t just designing a case. They were trying to teach civility to swim.

The Oyster and the Channel

The English Channel in October is less a body of water and more a particularly vindictive slab of granite. On the morning of October 7, 1927, it was busy trying to freeze the willpower out of Mercedes Gleitze, a London stenographer attempting to swim across it. A career move her colleagues likely considered ‘imaginative.’

Around her neck, ribbon strapped above the relentless chop, was a small steel contraption. An object designed for soirées and polite glances, now doing its best impression of a submarine.

The watch was there because Hans Wilsdorf, founder of Rolex, had solved the great riddle, and wasn’t about to let modesty ruin the announcement. His answer to the problem of water and dust was the 1926 Oyster case, a marvel of hermetic engineering. Its bezel, caseback, and crown all screwed down to form an impenetrable vault, protecting the delicate movement within.

But invention alone was not enough. Proof was the currency of belief. Wilsdorf needed a bigger stage, and nothing got bigger than the English Channel, attempting to drown the star that would be Mercedes Gleitze.

For more than ten hours, she battled the waves and the creeping, brutal cold. The tide and the temperature were against her. When Gleitze was finally pulled from the water, exhausted but triumphant, the small Oyster was not just surviving; it was keeping perfect time. The water had failed to breach its walls.

Wilsdorf, never one to waste a miracle, took out a full-page ad on the front of the Daily Mail, declaring “The Triumph of the Rolex Oyster.” It wasn’t just a technical win, but a marketing masterstroke. The watch had held its breath, and the world applauded its lungs.

The Age of the Tool (Watch)

That advertisement in the Daily Mail did more than sell a watch. It reversed an age-old anxiety. The wristwatch, once a delicate trinket, was no longer the thing to protect; it was the thing that protected you.

Thus began the quiet arms race of endurance. Waterproofing was no longer a novelty but a calling and would very, very soon be a given. Across Switzerland, cases thickened, crowns tightened, and balance wheels marched on behind glass that refused to mist. Watchmakers began to imagine their creations not as ornaments, but as instruments.

By the late 1930s, this new faith in fortitude had become a language of its own. Mountaineers needed watches that could withstand extreme temperatures and altitudes; engineers wanted ones that wouldn’t flinch at oil or dust. And in the hidden docks of Italy, Panerai was quietly building instruments meant to be read in the black silence of the sea.

These were not yet the tool watches the world would come to know, but their blueprints.

The watch had stopped fearing the elements and begun to negotiate with them. The migration was nearly complete. Time had shifted from pocket to wrist, from a fragile accessory to faithful accomplice. But a final transformation still waited below the surface, where water pressure was measured not in raindrops, but in fathoms.