Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

A Parsi, a Tam-Brahm, and a Frenchman walk into a bar. Only they don’t. Because this is not the opening line of a tired joke, instead, they walk into an idea. An idea called Titan.

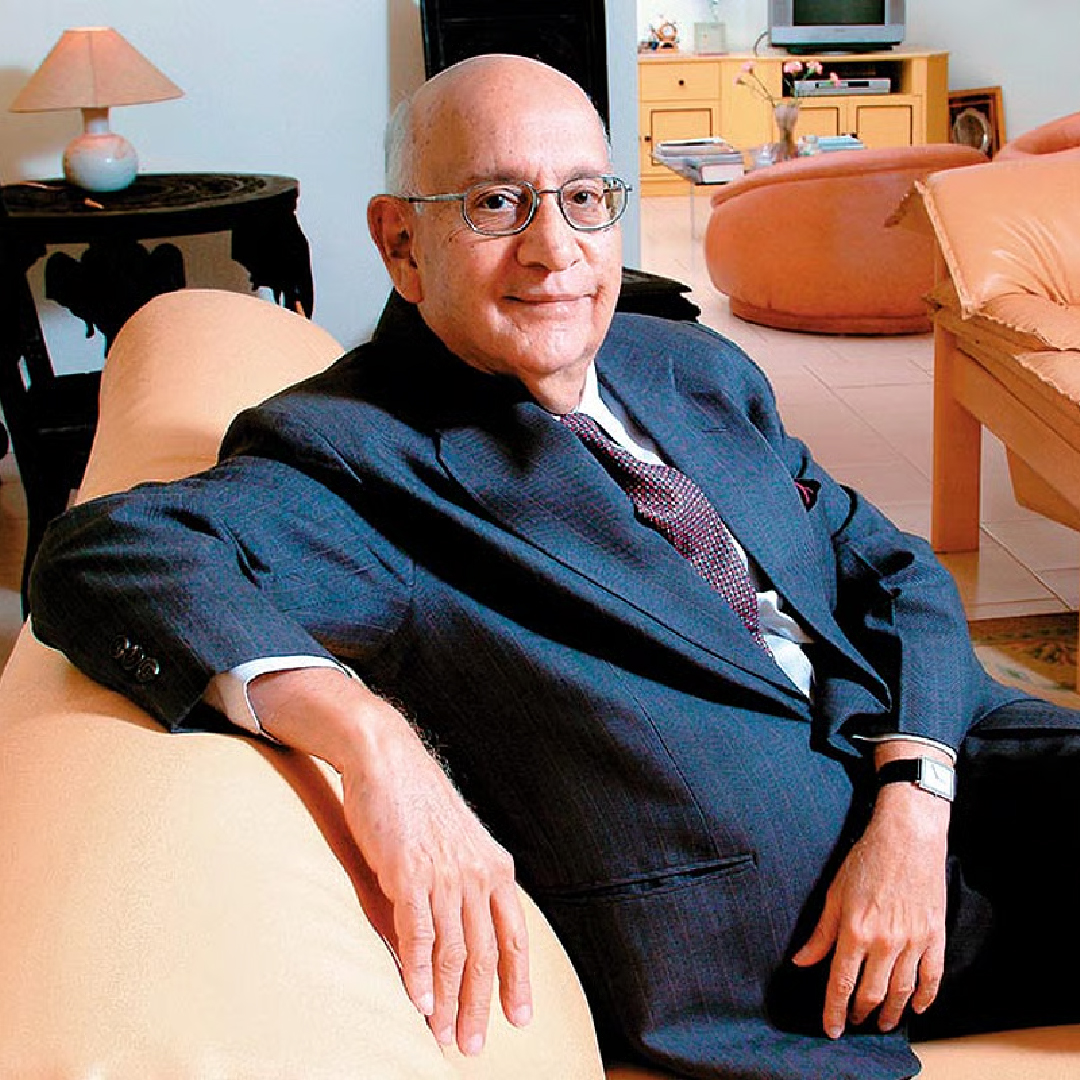

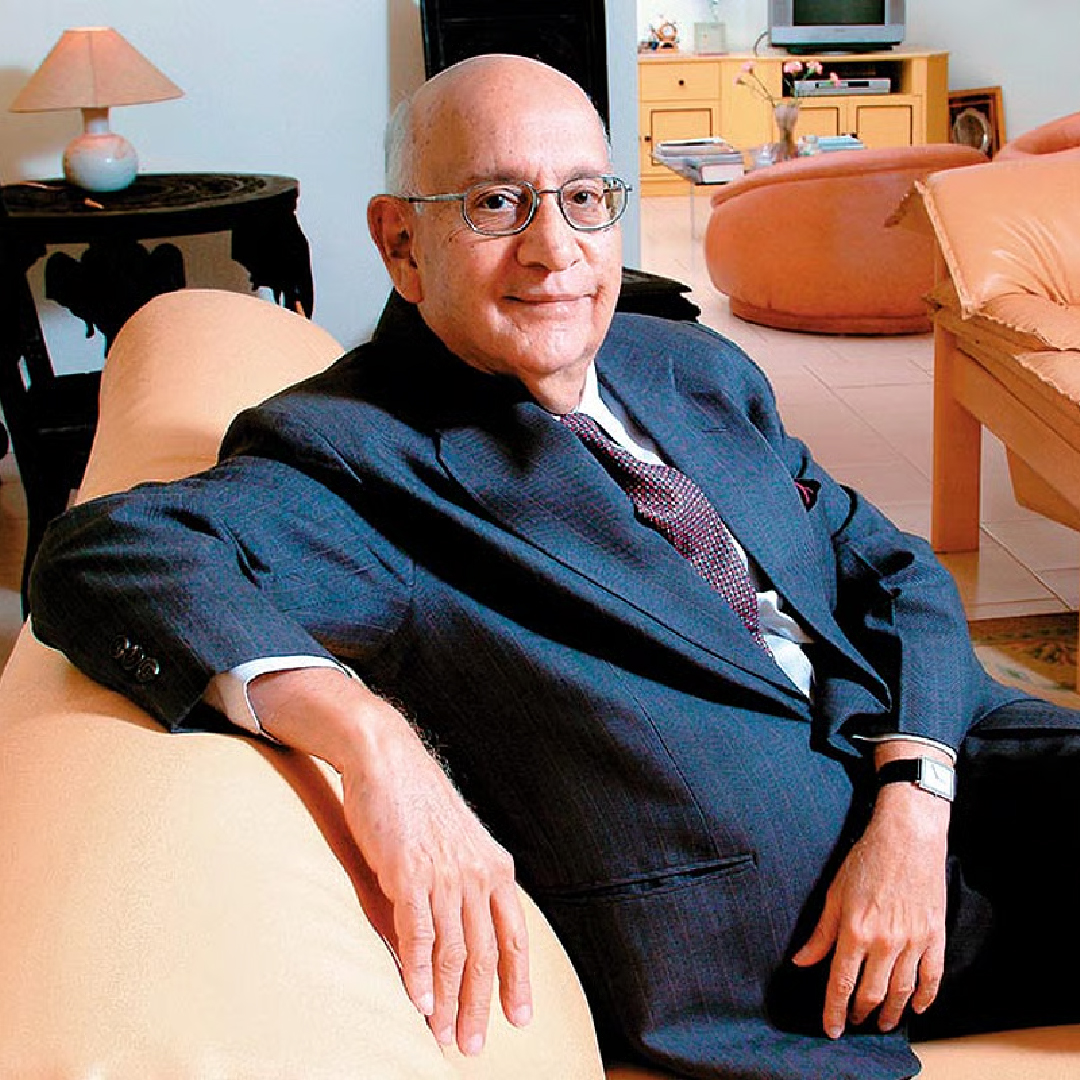

The funny thing is that the world was not exactly waiting for it. In September 1982, inside a North Block office where the walls had heard stranger proposals, the Secretary of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry listened to the Tata delegation for all of two minutes before shutting the door on the dream. He looked at Minoo Mody, then the chief of Tata Sons, straight in the eye and said, “Take it from me, Mr Mody, the Tatas will never make watches,” and then dismissed the team with the briskness of a man clearing his desk before lunch.

Two minutes. That was the official forecast for Titan’s future.

The Madras Loophole

That ‘no’ from Delhi was not personal. It was theological. The entire business of watchmaking had been reserved for the small-scale sector, and the Tatas were about as small-scale as the Navy is a rowing club. The rulebook said no, so Delhi said no. Stamp, file, forget.

Except Xerxes Desai did not forget. If the front door in North Block were bolted shut, he would go looking for a crack in the foundation. And there was one. The Centre controlled the license, but it never said the applicant had to be Tata. A new entity could ask. Preferably, one with a state government that believed in possibilities more than prohibitions.

So the team flew to Madras, to TIDCO, where Iravatham Mahadevan listened with the calm of a man who spent his evenings trying to unravel the Indus Script. He had met Xerxes years earlier, and between the historian and the aesthete, the idea found shelter. Titan Watches Ltd was born, half Tata, half Tamil Nadu, and entirely improbable.

The Frenchman’s Spark

The new company had the paperwork. What it did not have was the ability to make a modern watch. Quartz was the future, and India did not yet know how to build the tiny crystal heart that made a quartz watch tick.

So the team went looking for someone who did, and they found France Ebauches. Not a vendor, but a partner willing to transfer technology, train Indian engineers and slowly hand over an entire craft.

It was expensive, risky and almost reckless for a country that still counted foreign exchange like loose change. But it gave Titan its spark. It also gave it a clock. The idea was in place, the license secured, the partner chosen.

All they needed now was a place to build the dream. They found it on a quiet patch of land outside Bangalore.

Hosur. A location chosen not for glamour, but for grit. And in 1987, the first Titan started ticking.

A Boy Courts Titan, A Country Courts Audacity

The first watch I ever wore was a small, gold-plated Titan I borrowed for an exam. It belonged to my aunt, and it was far too delicate for the battlefield of a school corridor. I wore it because I thought it would help me stay calm in the face of questions I was clueless about. Instead, it turned me into the punchline of the week.

What I did not realise then was that I was wearing a fragment of a quiet revolution.

The nineties were a peculiar decade. The economy had just opened. Cable television had barged into our living rooms. Sachin Tendulkar had become a permanent fixture of our national imagination and ambition. It was a decade of denim, foreign chocolates in family’s friend’s suitcases, and the faint, thrilling sense that India could be something more than earnest potential. We were learning to stand a little taller, to ask for finer things, to loosen the grip of modesty that had defined the eighties.

In 1994, amid this cultural growth spurt, Xerxes Desai gathered his engineers in Hosur and posed a question that seemed simple until you tried to answer it. Could they make the world’s slimmest watch? Not a slimmer watch. The slimmest in the world.

It was the sort of request that only a certain kind of gentle audacity could produce. Xerxes believed that beauty was a legitimate goal. He believed India could create things that did not rely on apology or imitation. The engineers must have stared at him in quiet disbelief, but they began. For eight years, they chipped away at millimetres with the discipline of monks and the optimism of artists.

Outside that factory, the country itself was shrinking its own insecurities. Technology parks were taking shape. Call centres were finding their accents. Young India was beginning to move from caution to confidence. Asking for the world’s slimmest watch did not feel like a fantasy. It felt like timing.

In 2002, Titan Edge finally arrived. A watch so thin it looked like someone had sketched it onto your wrist with a drafting pencil. Just over three millimetres at its slimmest. It did not shout. It did not posture. It simply existed, serene and certain, as if it had always been possible for a company once dismissed in a two-minute meeting to quietly outdo the world.

Edge was not merely a watch. It was a whisper of self-belief. And in a decade when India was figuring out who it could become, that whisper mattered.

A Beating Heart

For a long time, Titan’s story ran on quartz. Clean, precise, democratic. It suited the country we were then, a place that liked things to work without fuss. But somewhere along the way, a curious shift began. India grew more comfortable with nuance. Craft stopped feeling indulgent. A watch did not have to be practical to justify its place on the wrist. It could simply be interesting.

Titan stepped into mechanicals the way it had done most things. Quietly. No fanfare, no grand declarations. A few automatics here, a skeleton dial there, and suddenly you realised the company that once had to smuggle an idea through a bureaucratic loophole was now tinkering with springs and rotors like a watchmaker with an itch.

Some of this came through partnerships, some through acquisitions, some through slow, methodical learning. They even picked up Americhron along the way, a small but telling move for a company that once began by importing every heartbeat of its watches. The results were not meant to impress Switzerland. They were meant to say something simpler. That India had the patience to try.

Over time, that patience began to show. First came a remarkably slim automatic, the kind of watch that suggested Titan’s engineers were enjoying themselves. Then arrived the tourbillons. Two of them. Including one with a marble dial hand-painted by Padma Shri Shakir Ali. These are not the pieces you automatically associate with Titan, but perhaps that is the point. It is easy to overlook what grows quietly.

From Two Minutes to Two Seconds

Today, Titan sells a watch every two seconds. It is a statistic that would have sounded absurd in that North Block office in 1982. The Parsi, the Tam-Brahm, and the Frenchman may have walked into an idea, but the idea had to survive policy, doubt, loopholes, and the natural shyness of a young nation.

It survived because a few people believed that India could make objects that were not apologetic. Objects that could sit quietly on a wrist and still say something.

I think of that sometimes. The boy, borrowing a delicate Titan for an exam, was laughed at in the corridor, not knowing he was wearing the start of a shift. The country around him opening its economy, finding its voice, daring itself in small, almost invisible ways.

Titan did not change India. But it nudged it. It made the wrist a little braver. It taught us that design was not foreign and ambition did not require permission. It showed that a homegrown idea, given time and care, can end up outlasting the certainty of those who once wrote it off in two minutes.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

A Parsi, a Tam-Brahm, and a Frenchman walk into a bar. Only they don’t. Because this is not the opening line of a tired joke, instead, they walk into an idea. An idea called Titan.

The funny thing is that the world was not exactly waiting for it. In September 1982, inside a North Block office where the walls had heard stranger proposals, the Secretary of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry listened to the Tata delegation for all of two minutes before shutting the door on the dream. He looked at Minoo Mody, then the chief of Tata Sons, straight in the eye and said, “Take it from me, Mr Mody, the Tatas will never make watches,” and then dismissed the team with the briskness of a man clearing his desk before lunch.

Two minutes. That was the official forecast for Titan’s future.

The Madras Loophole

That ‘no’ from Delhi was not personal. It was theological. The entire business of watchmaking had been reserved for the small-scale sector, and the Tatas were about as small-scale as the Navy is a rowing club. The rulebook said no, so Delhi said no. Stamp, file, forget.

Except Xerxes Desai did not forget. If the front door in North Block were bolted shut, he would go looking for a crack in the foundation. And there was one. The Centre controlled the license, but it never said the applicant had to be Tata. A new entity could ask. Preferably, one with a state government that believed in possibilities more than prohibitions.

So the team flew to Madras, to TIDCO, where Iravatham Mahadevan listened with the calm of a man who spent his evenings trying to unravel the Indus Script. He had met Xerxes years earlier, and between the historian and the aesthete, the idea found shelter. Titan Watches Ltd was born, half Tata, half Tamil Nadu, and entirely improbable.

The Frenchman’s Spark

The new company had the paperwork. What it did not have was the ability to make a modern watch. Quartz was the future, and India did not yet know how to build the tiny crystal heart that made a quartz watch tick.

So the team went looking for someone who did, and they found France Ebauches. Not a vendor, but a partner willing to transfer technology, train Indian engineers and slowly hand over an entire craft.

It was expensive, risky and almost reckless for a country that still counted foreign exchange like loose change. But it gave Titan its spark. It also gave it a clock. The idea was in place, the license secured, the partner chosen.

All they needed now was a place to build the dream. They found it on a quiet patch of land outside Bangalore.

Hosur. A location chosen not for glamour, but for grit. And in 1987, the first Titan started ticking.

A Boy Courts Titan, A Country Courts Audacity

The first watch I ever wore was a small, gold-plated Titan I borrowed for an exam. It belonged to my aunt, and it was far too delicate for the battlefield of a school corridor. I wore it because I thought it would help me stay calm in the face of questions I was clueless about. Instead, it turned me into the punchline of the week.

What I did not realise then was that I was wearing a fragment of a quiet revolution.

The nineties were a peculiar decade. The economy had just opened. Cable television had barged into our living rooms. Sachin Tendulkar had become a permanent fixture of our national imagination and ambition. It was a decade of denim, foreign chocolates in family’s friend’s suitcases, and the faint, thrilling sense that India could be something more than earnest potential. We were learning to stand a little taller, to ask for finer things, to loosen the grip of modesty that had defined the eighties.

In 1994, amid this cultural growth spurt, Xerxes Desai gathered his engineers in Hosur and posed a question that seemed simple until you tried to answer it. Could they make the world’s slimmest watch? Not a slimmer watch. The slimmest in the world.

It was the sort of request that only a certain kind of gentle audacity could produce. Xerxes believed that beauty was a legitimate goal. He believed India could create things that did not rely on apology or imitation. The engineers must have stared at him in quiet disbelief, but they began. For eight years, they chipped away at millimetres with the discipline of monks and the optimism of artists.

Outside that factory, the country itself was shrinking its own insecurities. Technology parks were taking shape. Call centres were finding their accents. Young India was beginning to move from caution to confidence. Asking for the world’s slimmest watch did not feel like a fantasy. It felt like timing.

In 2002, Titan Edge finally arrived. A watch so thin it looked like someone had sketched it onto your wrist with a drafting pencil. Just over three millimetres at its slimmest. It did not shout. It did not posture. It simply existed, serene and certain, as if it had always been possible for a company once dismissed in a two-minute meeting to quietly outdo the world.

Edge was not merely a watch. It was a whisper of self-belief. And in a decade when India was figuring out who it could become, that whisper mattered.

A Beating Heart

For a long time, Titan’s story ran on quartz. Clean, precise, democratic. It suited the country we were then, a place that liked things to work without fuss. But somewhere along the way, a curious shift began. India grew more comfortable with nuance. Craft stopped feeling indulgent. A watch did not have to be practical to justify its place on the wrist. It could simply be interesting.

Titan stepped into mechanicals the way it had done most things. Quietly. No fanfare, no grand declarations. A few automatics here, a skeleton dial there, and suddenly you realised the company that once had to smuggle an idea through a bureaucratic loophole was now tinkering with springs and rotors like a watchmaker with an itch.

Some of this came through partnerships, some through acquisitions, some through slow, methodical learning. They even picked up Americhron along the way, a small but telling move for a company that once began by importing every heartbeat of its watches. The results were not meant to impress Switzerland. They were meant to say something simpler. That India had the patience to try.

Over time, that patience began to show. First came a remarkably slim automatic, the kind of watch that suggested Titan’s engineers were enjoying themselves. Then arrived the tourbillons. Two of them. Including one with a marble dial hand-painted by Padma Shri Shakir Ali. These are not the pieces you automatically associate with Titan, but perhaps that is the point. It is easy to overlook what grows quietly.

From Two Minutes to Two Seconds

Today, Titan sells a watch every two seconds. It is a statistic that would have sounded absurd in that North Block office in 1982. The Parsi, the Tam-Brahm, and the Frenchman may have walked into an idea, but the idea had to survive policy, doubt, loopholes, and the natural shyness of a young nation.

It survived because a few people believed that India could make objects that were not apologetic. Objects that could sit quietly on a wrist and still say something.

I think of that sometimes. The boy, borrowing a delicate Titan for an exam, was laughed at in the corridor, not knowing he was wearing the start of a shift. The country around him opening its economy, finding its voice, daring itself in small, almost invisible ways.

Titan did not change India. But it nudged it. It made the wrist a little braver. It taught us that design was not foreign and ambition did not require permission. It showed that a homegrown idea, given time and care, can end up outlasting the certainty of those who once wrote it off in two minutes.