Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

On a pebble beach somewhere along the Mediterranean, a sports diver adjusts the straps of his Aqua-Lung and checks his wristwatch. It is purposeful rather than elegant, a piece of equipment more than an accessory. A black dial. Distinctly shaped luminous hands. A steel case that catches the light once, then disappears under neoprene. He rotates the bezel, aligns it with the minute hand, and commits the minute marker to muscle memory. Time will be counted downward from this point on.

The watch is a Rolex Submariner, or something very much like it. Compact enough to live on the wrist between dives, capable enough to be trusted beneath the surface. It carries its logic from military necessity into a civilian world that is only just beginning to explore depth as leisure.

As diving became recreational, the demands placed on the watch shifted, if only slightly. Reliability remained non-negotiable, but wearability began to matter in new ways.

The Art of Yielding

By the mid-1950s, the dive watch had reached something like consensus. Early examples began appearing on wrists far removed from naval procurement offices, their purpose intact even as their audience widened. The problem, it seemed, had been solved.

But engineering rarely rests on the first satisfactory answer.

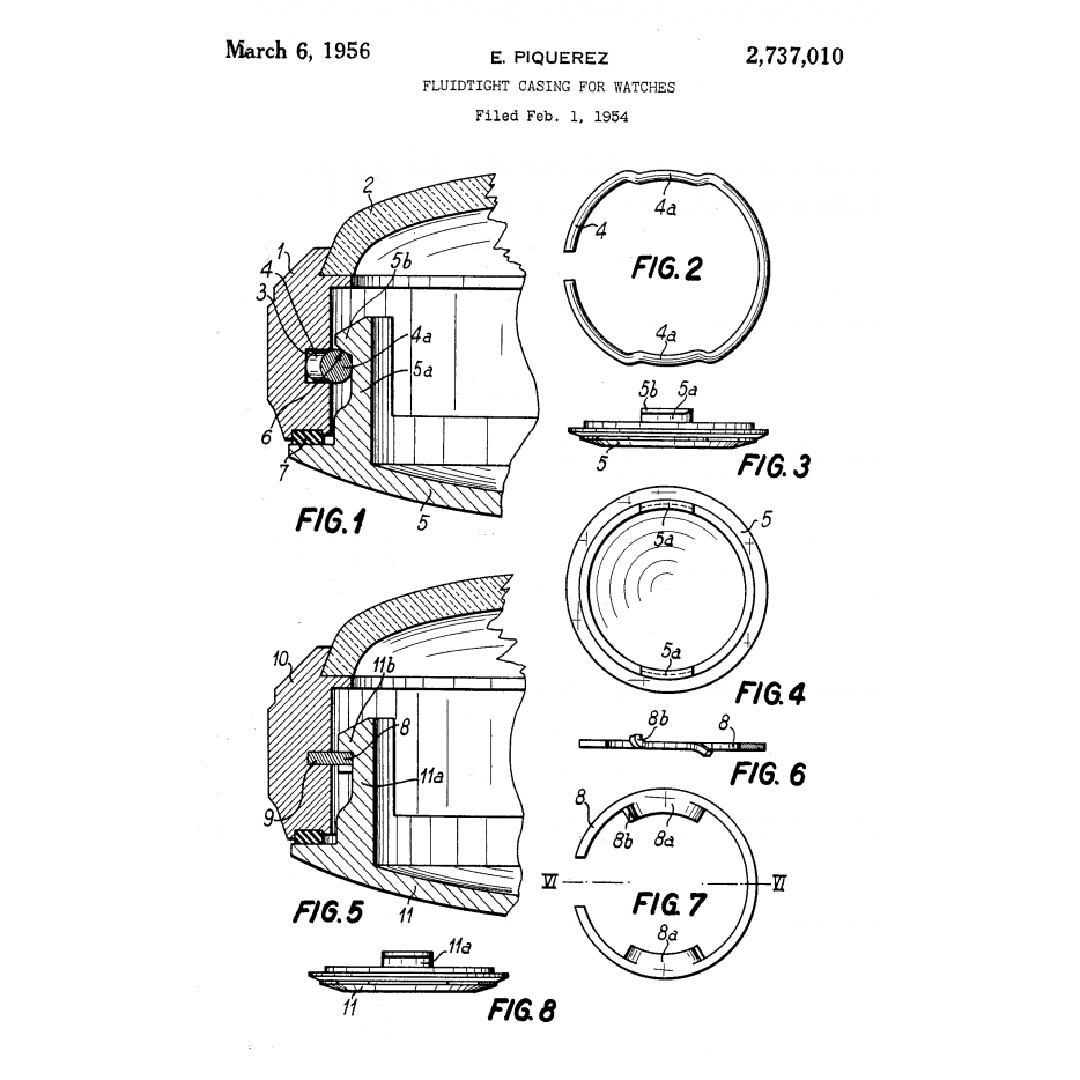

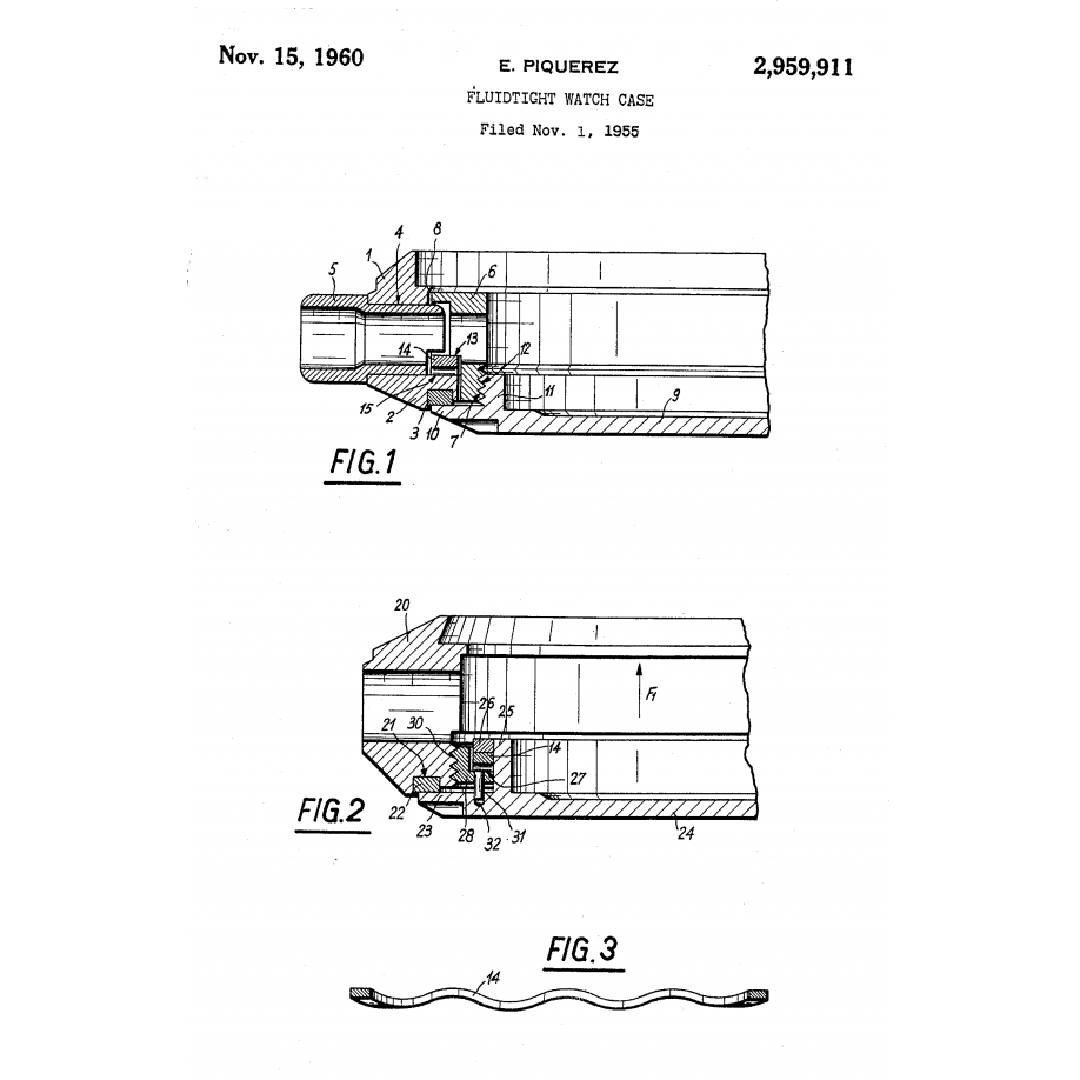

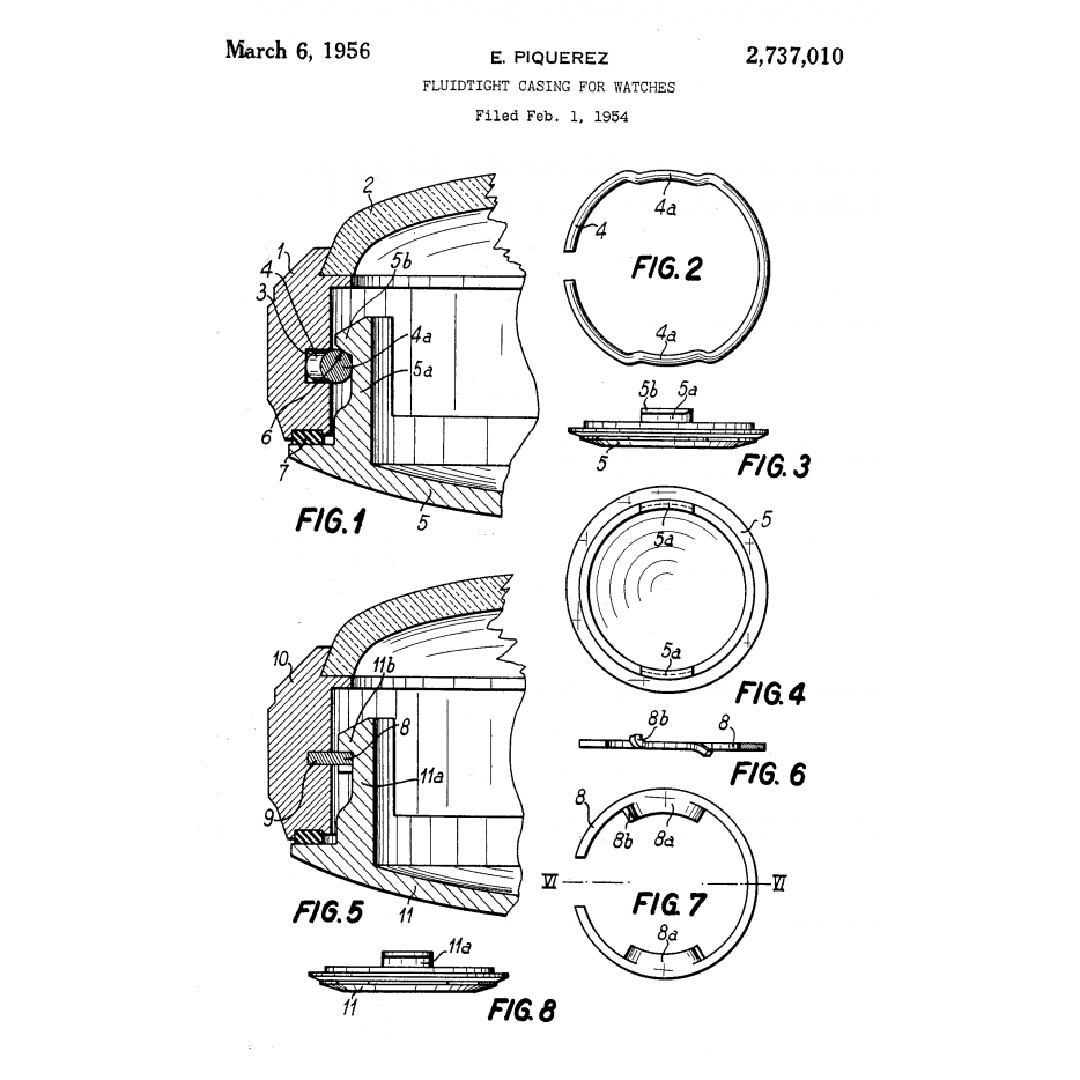

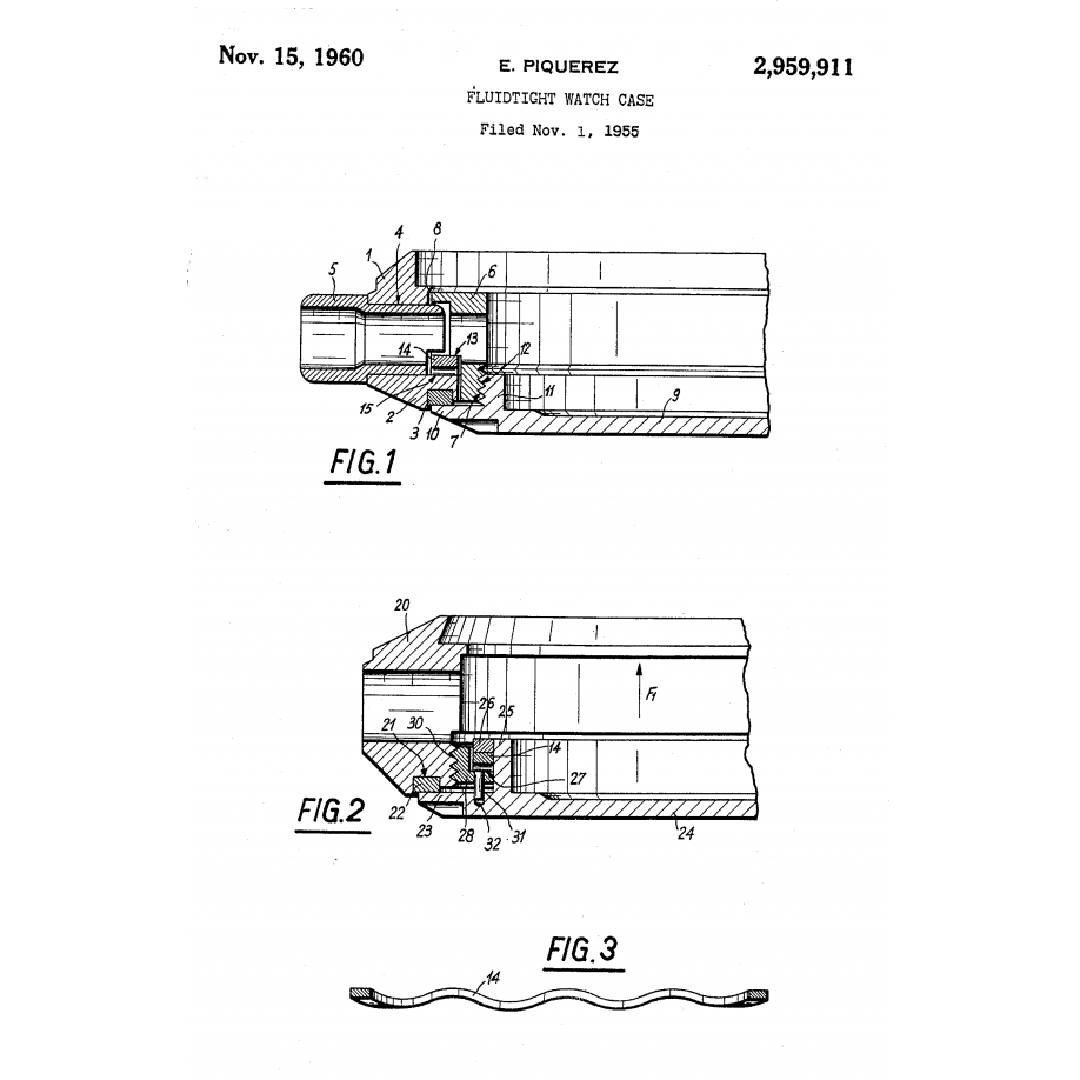

If pressure was the problem, perhaps it did not always need to be resisted. Perhaps it could be managed. Under the right conditions, perhaps it could even be made useful. That question occupied a small circle of engineers and specialist case makers in Switzerland. Among them was E. Piquerez S.A., better known as EPSA, which developed what would become known as the Super Compressor case in the mid-1950s.

In a conventional dive watch, sealing is a blunt instrument. The caseback is screwed down hard against the gasket, the seal already under stress before the watch ever touches water. As pressure increases, the gasket is compressed further, performing its task but paying for it in wear. The logic is simple and effective, but it assumes permanence: tight at the surface, tighter below.

The Super Compressor approached the same problem from a different angle. Its caseback was not rigidly fixed but held in tension by a spring. At shallow depths, the seal was engaged but not fully loaded. As external pressure increased, the caseback was allowed to move inward slightly, progressively compressing the gasket. Full compression occurred only when depth demanded it.

In this arrangement, pressure ceased to be an adversary and became a collaborator. The deeper the watch descended, the more secure the seal became. At the surface, the gasket was spared unnecessary strain. At depth, it was exactly as tight as it needed to be.

The consequences were practical rather than theoretical. Super Compressor cases achieved impressive depth ratings for their era, often up to six hundred feet.

Just as significantly, reduced gasket fatigue improved longevity and extended service intervals. It was an elegant solution to a problem that most manufacturers addressed through mass and force.

EPSA produced several variations on the theme, but it is the twin-crown Super Compressor that has endured. One crown set the time. The other, usually positioned at two o’clock, operated an internal rotating timing bezel safely tucked beneath the crystal.

In time, it became the visual shorthand for the idea itself, inspiring reinterpretations long after the original cases had slipped quietly out of production.

The Leisure Diver

Throughout the late 1950s and into the 1970s, the Super Compressor case migrated quietly across the Swiss watch industry, adopted by brands large and small. EPSA supplied the idea, but what emerged depended on the audience each of these brands spoke to.

The most famous expression of the idea, and certainly the most ambitious, was the Jaeger-LeCoultre Polaris. It paired the twin-crown compressor case with a triple-layer dial and an alarm complication, transforming the watch into a fully kitted instrument rather than a simple timer. Over-engineered, expensive, and unapologetically complex, the Polaris treated underwater timekeeping as a multi-sensory problem. It did not merely mark danger; it announced it.

Universal Genève took a different approach. The Polerouter Sub used the same compressor architecture to produce a quieter, more urban composition. It retained the internal bezel and twin crowns but refined the execution. A dive-watch that assumed its wearer might surface, rinse off, and go straight to dinner.

Other manufacturers followed, each bending the idea toward their own markets. Longines explored symmetry and restraint. Hamilton and Bulova adapted the compressor case for broader civilian appeal. Benrus pressed it back into service. The underlying architecture remained the same, but the watches it produced varied widely in tone and intent.

What united them was the belief that pressure could be accommodated rather than resisted, and that a dive watch need not announce itself.

A Curious (Disappearing) Case

By the late 1960s, diving was becoming orderly. Training manuals thickened. Standards hardened. What had once been improvisational and exploratory began to look procedural. With that shift came a preference for tools that were immediately legible, easy to teach, and difficult to misunderstand.

The bezel diver fitted this world perfectly. Its logic sat on the outside. You could see what it did. You could explain it in a sentence. You could hand it to someone and trust that they would use it correctly, even if they didn’t fully understand why it worked.

The Super Compressor was never that kind of watch. Its best idea remained invisible until it was needed. There were practical inconveniences, too. Two crowns invite questions, even when the answers are sound. Spring-loaded casebacks demand tighter tolerances, the sort that reward care rather than scale. Servicing them requires familiarity, not just competence. None of these were fatal flaws, but they were frictions - and they accumulated quickly.

Then the ground shifted entirely. Quartz arrived and rendered the argument moot. In its wake, subtle engineering philosophies became footnotes. EPSA disappeared quietly, as specialist suppliers often do. Other manufacturers were absorbed, or retreated to safer, more predictable corners of their catalogues.

The Inevitable Return

What disappeared, in the end, was not the idea, but the conditions that had allowed it to matter. The Super Compressor belonged to a brief interlude when watches were still expected to be instruments, yet had begun to be worn as companions. An era when engineering curiosity could coexist with comfort. When a solution did not yet need to explain itself at a glance, because the wearer was assumed to be curious enough to ask why.

That moment passed, and the bezel diver became the default. It was clearer, louder, easier to trust. It spoke effortlessly to the inner adventurer, the unlost who might sit at a desk but wants a single glance at the wrist to suggest readiness. For depth, danger, or at least the idea of it.

The Super Compressor slipped into the margins. And perhaps that is its quiet legacy, beyond its challenge to the archetype. It is proof that the path from lifesaver to lifestyle was never a straight line.

And yet, ideas like this rarely disappear completely. They wait.

In recent years, the Super Compressor silhouette has resurfaced, revived by small independent makers and cautiously reclaimed by larger houses revisiting their own archives. It is easy to dismiss this as nostalgia. But standing so far outside the mainstream diver silhouette, the compressor now reads less like retro styling and more like a deliberate choice. A watch for someone who still wants to acknowledge an inner adventurer, but without announcing it.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

On a pebble beach somewhere along the Mediterranean, a sports diver adjusts the straps of his Aqua-Lung and checks his wristwatch. It is purposeful rather than elegant, a piece of equipment more than an accessory. A black dial. Distinctly shaped luminous hands. A steel case that catches the light once, then disappears under neoprene. He rotates the bezel, aligns it with the minute hand, and commits the minute marker to muscle memory. Time will be counted downward from this point on.

The watch is a Rolex Submariner, or something very much like it. Compact enough to live on the wrist between dives, capable enough to be trusted beneath the surface. It carries its logic from military necessity into a civilian world that is only just beginning to explore depth as leisure.

As diving became recreational, the demands placed on the watch shifted, if only slightly. Reliability remained non-negotiable, but wearability began to matter in new ways.

The Art of Yielding

By the mid-1950s, the dive watch had reached something like consensus. Early examples began appearing on wrists far removed from naval procurement offices, their purpose intact even as their audience widened. The problem, it seemed, had been solved.

But engineering rarely rests on the first satisfactory answer.

If pressure was the problem, perhaps it did not always need to be resisted. Perhaps it could be managed. Under the right conditions, perhaps it could even be made useful. That question occupied a small circle of engineers and specialist case makers in Switzerland. Among them was E. Piquerez S.A., better known as EPSA, which developed what would become known as the Super Compressor case in the mid-1950s.

In a conventional dive watch, sealing is a blunt instrument. The caseback is screwed down hard against the gasket, the seal already under stress before the watch ever touches water. As pressure increases, the gasket is compressed further, performing its task but paying for it in wear. The logic is simple and effective, but it assumes permanence: tight at the surface, tighter below.

The Super Compressor approached the same problem from a different angle. Its caseback was not rigidly fixed but held in tension by a spring. At shallow depths, the seal was engaged but not fully loaded. As external pressure increased, the caseback was allowed to move inward slightly, progressively compressing the gasket. Full compression occurred only when depth demanded it.

In this arrangement, pressure ceased to be an adversary and became a collaborator. The deeper the watch descended, the more secure the seal became. At the surface, the gasket was spared unnecessary strain. At depth, it was exactly as tight as it needed to be.

The consequences were practical rather than theoretical. Super Compressor cases achieved impressive depth ratings for their era, often up to six hundred feet.

Just as significantly, reduced gasket fatigue improved longevity and extended service intervals. It was an elegant solution to a problem that most manufacturers addressed through mass and force.

EPSA produced several variations on the theme, but it is the twin-crown Super Compressor that has endured. One crown set the time. The other, usually positioned at two o’clock, operated an internal rotating timing bezel safely tucked beneath the crystal.

In time, it became the visual shorthand for the idea itself, inspiring reinterpretations long after the original cases had slipped quietly out of production.

The Leisure Diver

Throughout the late 1950s and into the 1970s, the Super Compressor case migrated quietly across the Swiss watch industry, adopted by brands large and small. EPSA supplied the idea, but what emerged depended on the audience each of these brands spoke to.

The most famous expression of the idea, and certainly the most ambitious, was the Jaeger-LeCoultre Polaris. It paired the twin-crown compressor case with a triple-layer dial and an alarm complication, transforming the watch into a fully kitted instrument rather than a simple timer. Over-engineered, expensive, and unapologetically complex, the Polaris treated underwater timekeeping as a multi-sensory problem. It did not merely mark danger; it announced it.

Universal Genève took a different approach. The Polerouter Sub used the same compressor architecture to produce a quieter, more urban composition. It retained the internal bezel and twin crowns but refined the execution. A dive-watch that assumed its wearer might surface, rinse off, and go straight to dinner.

Other manufacturers followed, each bending the idea toward their own markets. Longines explored symmetry and restraint. Hamilton and Bulova adapted the compressor case for broader civilian appeal. Benrus pressed it back into service. The underlying architecture remained the same, but the watches it produced varied widely in tone and intent.

What united them was the belief that pressure could be accommodated rather than resisted, and that a dive watch need not announce itself.

A Curious (Disappearing) Case

By the late 1960s, diving was becoming orderly. Training manuals thickened. Standards hardened. What had once been improvisational and exploratory began to look procedural. With that shift came a preference for tools that were immediately legible, easy to teach, and difficult to misunderstand.

The bezel diver fitted this world perfectly. Its logic sat on the outside. You could see what it did. You could explain it in a sentence. You could hand it to someone and trust that they would use it correctly, even if they didn’t fully understand why it worked.

The Super Compressor was never that kind of watch. Its best idea remained invisible until it was needed. There were practical inconveniences, too. Two crowns invite questions, even when the answers are sound. Spring-loaded casebacks demand tighter tolerances, the sort that reward care rather than scale. Servicing them requires familiarity, not just competence. None of these were fatal flaws, but they were frictions - and they accumulated quickly.

Then the ground shifted entirely. Quartz arrived and rendered the argument moot. In its wake, subtle engineering philosophies became footnotes. EPSA disappeared quietly, as specialist suppliers often do. Other manufacturers were absorbed, or retreated to safer, more predictable corners of their catalogues.

The Inevitable Return

What disappeared, in the end, was not the idea, but the conditions that had allowed it to matter. The Super Compressor belonged to a brief interlude when watches were still expected to be instruments, yet had begun to be worn as companions. An era when engineering curiosity could coexist with comfort. When a solution did not yet need to explain itself at a glance, because the wearer was assumed to be curious enough to ask why.

That moment passed, and the bezel diver became the default. It was clearer, louder, easier to trust. It spoke effortlessly to the inner adventurer, the unlost who might sit at a desk but wants a single glance at the wrist to suggest readiness. For depth, danger, or at least the idea of it.

The Super Compressor slipped into the margins. And perhaps that is its quiet legacy, beyond its challenge to the archetype. It is proof that the path from lifesaver to lifestyle was never a straight line.

And yet, ideas like this rarely disappear completely. They wait.

In recent years, the Super Compressor silhouette has resurfaced, revived by small independent makers and cautiously reclaimed by larger houses revisiting their own archives. It is easy to dismiss this as nostalgia. But standing so far outside the mainstream diver silhouette, the compressor now reads less like retro styling and more like a deliberate choice. A watch for someone who still wants to acknowledge an inner adventurer, but without announcing it.