Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

The room at the New York auction house smelled faintly of old money and cedar, the sort of place where silence is curated as carefully as the art. When the gavel finally fell, it didn’t just end the bidding; it startled the room back into reality. The final price hovered just shy of three million dollars.

The thing commanding that sum wasn’t a diamond or a lost manuscript. It was a woodblock print, barely larger than a sheet of legal paper. Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

I’ve lived with a copy of this image for years. It has hung on my wall during periods when life felt like a conquering adventure - swashbuckling, golden, full of momentum. I even used a version of it as the cover image for a book I co-edited.

It stayed there through quieter, more crushing nights too, when the ocean felt like it was slowly closing over my head.

Hokusai didn’t just paint water. He painted indifference. That terrifying, beautiful instant just before the world reminds you how little it cares.

Look closely. We fixate on the wave, but it’s the skiffs that matter. Low in the water. Crews crouched, not fighting, but bracing.

If you were in one of those wooden boats today, staring up at that wall of water, you wouldn’t want a gentleman diver. You wouldn’t want refinement.

You would want something that refuses to be polite.

The first of these answers did not arrive gently. It arrived as a refusal. A rejection of elegance, proportion, and anything that might compromise function. It did not try to reinterpret the dive watch; it tried to outgrow it. What emerged was not an evolution of the archetype, but a distortion of it. Something familiar, pushed past the point of comfort.

Some distort by excess. Others retreat behind walls.

The Fortress: Seiko Prospex Tuna

The problem arrived, as many good engineering problems do, in the form of a letter. In 1968, a professional saturation diver working out of Kure wrote to Seiko with a complaint: in helium-rich environments, the crystals of his watches were popping off. Of course, the problem could be solved by adding valves that allow gas to escape during decompression. Many Swiss brands would go that route, but Seiko took a different view. If pressure was getting in, the solution was not to vent it. It was to stop it altogether.

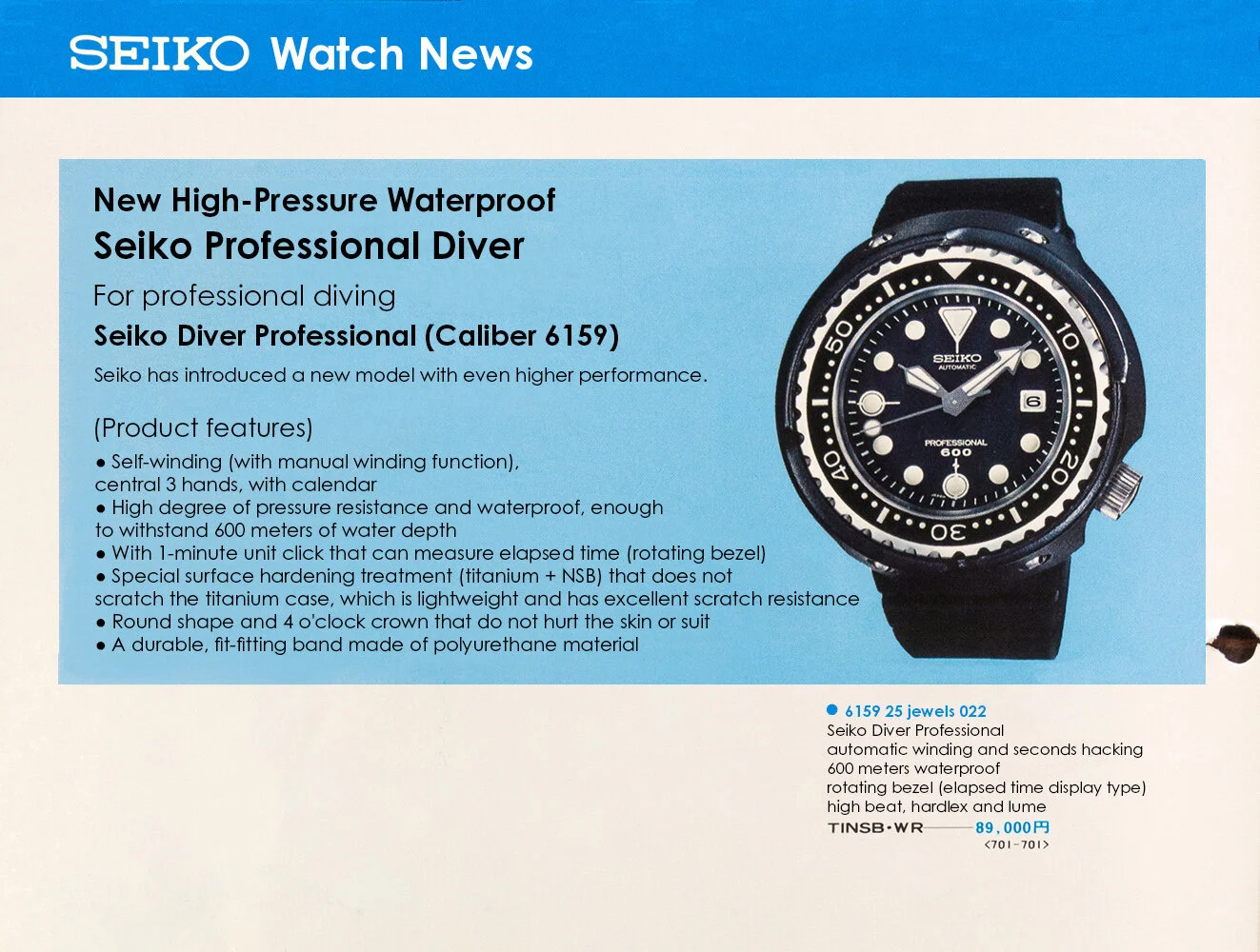

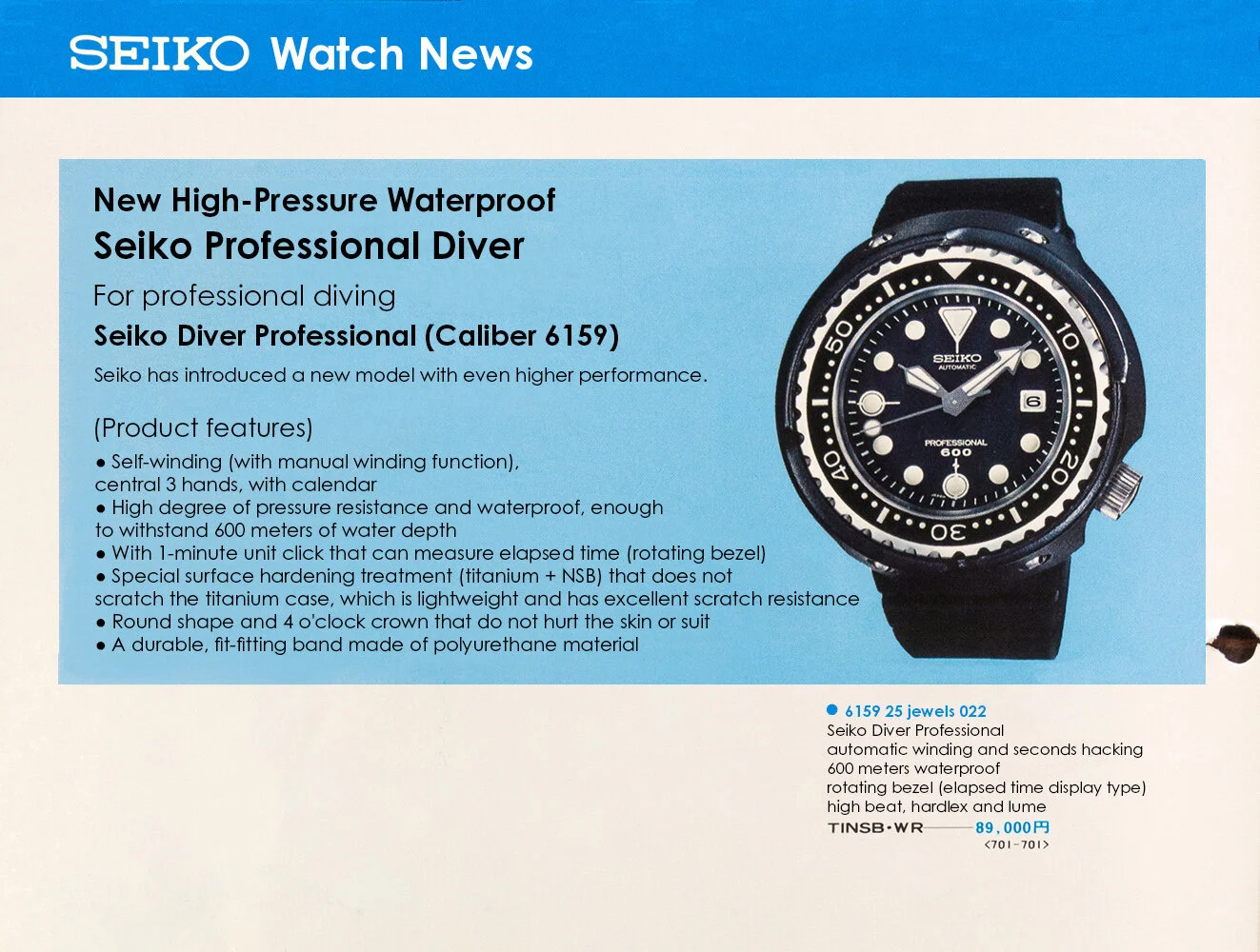

The result appeared in 1975 as the reference 6159-7010, a watch so unconcerned with convention that it barely resembles one. The movement was sealed inside a monocoque titanium case, eliminating a traditional caseback entirely. Around it, Seiko wrapped a massive, ceramic-coated shroud designed to absorb shocks and protect the watch from impact. There were no lugs. No exposed edges. Nothing delicate enough to be sacrificed.

The sealing was equally uncompromising. Seiko developed L-shaped gaskets specifically to prevent helium intrusion, rendering a release valve unnecessary. Where others added complexity, Seiko doubled down on isolation. The Tuna was not designed to negotiate with pressure. It was designed to ignore it.

On the wrist, it feels less like an accessory and more like armour. The nickname came easily. It looks like a tin can strapped to a strap. But the humour misses the point. This is not a watch shaped for wrists or wardrobes. It is shaped for environments where failure is not a metaphor.

The Mutant: Omega Seamaster Ploprof

If the Seamaster was designed to be worn by the spy licensed to kill, the Ploprof was built for the actual dirty work.

Released in 1970, even its name was brutally literal. Short for Plongeur Professionnel (or Professional Diver), this was a watch conceived for working divers, developed in collaboration with COMEX, and engineered around a single, non-negotiable instruction: it must not fail. Everything else was secondary.

The result looks less like a wristwatch and more like a piece of industrial hardware that happens to tell time. The asymmetrical case is a slab of steel shaped around problems rather than proportions. To prevent the crown from digging into the wrist during strenuous work, it was moved to the left side and buried beneath a massive locking nut. To eliminate the possibility of accidental timing errors, the bezel was locked in place entirely. The only way to turn it is to depress a bright orange button on the right flank of the case, an explicit action that replaces assumption with intent.

Even its construction reflects this mindset. The Ploprof uses a monobloc case, milled from a single piece of steel, eliminating a traditional caseback and removing one more potential point of failure.

The watch was heavy. It was angular. And it made no attempt to disappear under a cuff or flatter the wrist. Where the gentleman diver suggests preparedness, the Ploprof suggests inevitability.

It is not asking whether you trust it.

It assumes the conditions will be worse than you expect and prepares accordingly.

The Wizard: Sinn UX

If Seiko built a bunker and Omega engineered a submarine hatch, Sinn decided it had had enough of metal.

The engineers in Frankfurt approached the problem with a question that bordered on heresy. What if there were no pressure differential at all? What if the ocean couldn’t crush the watch because there was nothing inside it to crush?

The Sinn UX answers that question by refusing to contain air. The entire case is filled with a specialised oil. Liquids, unlike gases, are effectively incompressible. As a result, the pressure inside the watch always matches the pressure outside it. Whether at the surface or at extreme depth, the stress on the case remains unchanged.

In theory, this renders depth almost irrelevant. The limiting factor is no longer the case; it is the quartz movement and battery within it. In practice, the UX has been tested to depths that make conventional ratings feel performative.

The side effects are unsettling in the best possible way. The oil shares its refractive index with the sapphire crystal, eliminating reflections entirely. Underwater, the hands appear to rest directly on the dial's surface, as if the glass has vanished. The watch stops looking mechanical and begins behaving like an organism, adapted to its environment rather than protected from it.

The Assessor: Oris Aquis Depth Gauge

Every dive watch in history is united by a single imperative: keep the water out. The Oris Aquis Depth Gauge does the opposite.

Faced with the problem of integrating a mechanical depth gauge into a wristwatch without resorting to fragile mechanisms or electronic sensors, Oris arrived at a solution that feels almost indecent. They drilled a hole in the sapphire crystal.

The aperture leads to a precisely milled channel running around the outer circumference of the dial. As the diver descends, water enters this channel and compresses the air trapped inside it. The physics is elementary. Following Boyle’s Law, air volume decreases as pressure increases. The waterline itself becomes the indicator, advancing inward and tracing depth against a clearly printed scale.

There are no additional hands. No springs. No gears waiting to corrode. Nothing to wind, calibrate, or reset. The system is entirely passive, driven solely by ambient pressure. When the diver ascends, the trapped air expands, the water retreats, and the watch quietly resets itself.

For anyone raised on the doctrine of hermetic sealing, the concept is deeply uncomfortable. A deliberate puncture in the crystal runs counter to every instinct watchmaking cultivates. And yet, it works. Reliably. Repeatedly. With a blunt honesty that borders on defiance.

Where other dive watches attempt to outthink the ocean, the Aquis simply listens to it.

The Nature of the Beast

None of these watches are reasonable. They are heavy, specialised, and stubbornly indifferent to comfort. They do not slip under cuffs. They do not flatter wrists. They do not pretend to be anything other than what they are.

That is precisely the point.

Each of these designs exists because someone, somewhere, decided that the prevailing answer was insufficient. The archetype had become too polite. Too accommodating. Too willing to compromise in the name of wearability, taste, or market consensus. Faced with an ocean that remained unmoved by such considerations, they responded not with refinement but with excess.

These watches do not negotiate with their environment. They confront it. They isolate themselves from it, neutralise it, or invite it in on their own terms. They are not evolutions so much as declarations.

Looking back at Hokusai’s wave, this feels inevitable. When the water rises and the horizon tilts, lifestyle is a thin concept. What matters then is whether the object on your wrist was designed for ordinary days, or for the moment when the world reminds you how little it cares.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

The room at the New York auction house smelled faintly of old money and cedar, the sort of place where silence is curated as carefully as the art. When the gavel finally fell, it didn’t just end the bidding; it startled the room back into reality. The final price hovered just shy of three million dollars.

The thing commanding that sum wasn’t a diamond or a lost manuscript. It was a woodblock print, barely larger than a sheet of legal paper. Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

I’ve lived with a copy of this image for years. It has hung on my wall during periods when life felt like a conquering adventure - swashbuckling, golden, full of momentum. I even used a version of it as the cover image for a book I co-edited.

It stayed there through quieter, more crushing nights too, when the ocean felt like it was slowly closing over my head.

Hokusai didn’t just paint water. He painted indifference. That terrifying, beautiful instant just before the world reminds you how little it cares.

Look closely. We fixate on the wave, but it’s the skiffs that matter. Low in the water. Crews crouched, not fighting, but bracing.

If you were in one of those wooden boats today, staring up at that wall of water, you wouldn’t want a gentleman diver. You wouldn’t want refinement.

You would want something that refuses to be polite.

The first of these answers did not arrive gently. It arrived as a refusal. A rejection of elegance, proportion, and anything that might compromise function. It did not try to reinterpret the dive watch; it tried to outgrow it. What emerged was not an evolution of the archetype, but a distortion of it. Something familiar, pushed past the point of comfort.

Some distort by excess. Others retreat behind walls.

The Fortress: Seiko Prospex Tuna

The problem arrived, as many good engineering problems do, in the form of a letter. In 1968, a professional saturation diver working out of Kure wrote to Seiko with a complaint: in helium-rich environments, the crystals of his watches were popping off. Of course, the problem could be solved by adding valves that allow gas to escape during decompression. Many Swiss brands would go that route, but Seiko took a different view. If pressure was getting in, the solution was not to vent it. It was to stop it altogether.

The result appeared in 1975 as the reference 6159-7010, a watch so unconcerned with convention that it barely resembles one. The movement was sealed inside a monocoque titanium case, eliminating a traditional caseback entirely. Around it, Seiko wrapped a massive, ceramic-coated shroud designed to absorb shocks and protect the watch from impact. There were no lugs. No exposed edges. Nothing delicate enough to be sacrificed.

The sealing was equally uncompromising. Seiko developed L-shaped gaskets specifically to prevent helium intrusion, rendering a release valve unnecessary. Where others added complexity, Seiko doubled down on isolation. The Tuna was not designed to negotiate with pressure. It was designed to ignore it.

On the wrist, it feels less like an accessory and more like armour. The nickname came easily. It looks like a tin can strapped to a strap. But the humour misses the point. This is not a watch shaped for wrists or wardrobes. It is shaped for environments where failure is not a metaphor.

The Mutant: Omega Seamaster Ploprof

If the Seamaster was designed to be worn by the spy licensed to kill, the Ploprof was built for the actual dirty work.

Released in 1970, even its name was brutally literal. Short for Plongeur Professionnel (or Professional Diver), this was a watch conceived for working divers, developed in collaboration with COMEX, and engineered around a single, non-negotiable instruction: it must not fail. Everything else was secondary.

The result looks less like a wristwatch and more like a piece of industrial hardware that happens to tell time. The asymmetrical case is a slab of steel shaped around problems rather than proportions. To prevent the crown from digging into the wrist during strenuous work, it was moved to the left side and buried beneath a massive locking nut. To eliminate the possibility of accidental timing errors, the bezel was locked in place entirely. The only way to turn it is to depress a bright orange button on the right flank of the case, an explicit action that replaces assumption with intent.

Even its construction reflects this mindset. The Ploprof uses a monobloc case, milled from a single piece of steel, eliminating a traditional caseback and removing one more potential point of failure.

The watch was heavy. It was angular. And it made no attempt to disappear under a cuff or flatter the wrist. Where the gentleman diver suggests preparedness, the Ploprof suggests inevitability.

It is not asking whether you trust it.

It assumes the conditions will be worse than you expect and prepares accordingly.

The Wizard: Sinn UX

If Seiko built a bunker and Omega engineered a submarine hatch, Sinn decided it had had enough of metal.

The engineers in Frankfurt approached the problem with a question that bordered on heresy. What if there were no pressure differential at all? What if the ocean couldn’t crush the watch because there was nothing inside it to crush?

The Sinn UX answers that question by refusing to contain air. The entire case is filled with a specialised oil. Liquids, unlike gases, are effectively incompressible. As a result, the pressure inside the watch always matches the pressure outside it. Whether at the surface or at extreme depth, the stress on the case remains unchanged.

In theory, this renders depth almost irrelevant. The limiting factor is no longer the case; it is the quartz movement and battery within it. In practice, the UX has been tested to depths that make conventional ratings feel performative.

The side effects are unsettling in the best possible way. The oil shares its refractive index with the sapphire crystal, eliminating reflections entirely. Underwater, the hands appear to rest directly on the dial's surface, as if the glass has vanished. The watch stops looking mechanical and begins behaving like an organism, adapted to its environment rather than protected from it.

The Assessor: Oris Aquis Depth Gauge

Every dive watch in history is united by a single imperative: keep the water out. The Oris Aquis Depth Gauge does the opposite.

Faced with the problem of integrating a mechanical depth gauge into a wristwatch without resorting to fragile mechanisms or electronic sensors, Oris arrived at a solution that feels almost indecent. They drilled a hole in the sapphire crystal.

The aperture leads to a precisely milled channel running around the outer circumference of the dial. As the diver descends, water enters this channel and compresses the air trapped inside it. The physics is elementary. Following Boyle’s Law, air volume decreases as pressure increases. The waterline itself becomes the indicator, advancing inward and tracing depth against a clearly printed scale.

There are no additional hands. No springs. No gears waiting to corrode. Nothing to wind, calibrate, or reset. The system is entirely passive, driven solely by ambient pressure. When the diver ascends, the trapped air expands, the water retreats, and the watch quietly resets itself.

For anyone raised on the doctrine of hermetic sealing, the concept is deeply uncomfortable. A deliberate puncture in the crystal runs counter to every instinct watchmaking cultivates. And yet, it works. Reliably. Repeatedly. With a blunt honesty that borders on defiance.

Where other dive watches attempt to outthink the ocean, the Aquis simply listens to it.

The Nature of the Beast

None of these watches are reasonable. They are heavy, specialised, and stubbornly indifferent to comfort. They do not slip under cuffs. They do not flatter wrists. They do not pretend to be anything other than what they are.

That is precisely the point.

Each of these designs exists because someone, somewhere, decided that the prevailing answer was insufficient. The archetype had become too polite. Too accommodating. Too willing to compromise in the name of wearability, taste, or market consensus. Faced with an ocean that remained unmoved by such considerations, they responded not with refinement but with excess.

These watches do not negotiate with their environment. They confront it. They isolate themselves from it, neutralise it, or invite it in on their own terms. They are not evolutions so much as declarations.

Looking back at Hokusai’s wave, this feels inevitable. When the water rises and the horizon tilts, lifestyle is a thin concept. What matters then is whether the object on your wrist was designed for ordinary days, or for the moment when the world reminds you how little it cares.