Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

The English Channel in October is less a body of water and more a particularly vindictive slab of granite. So did Mercedes Gleitze, though her knowledge came the hard way. The announcement of her successful crossing, however, was not made breathlessly from the shore, nor shouted hoarse in triumph. It arrived instead as a full-page advertisement in the Daily Mail.

What mattered wasn’t whether the watch had conquered the elements - nature has a habit of correcting that language - but that, for the first time, a wristwatch could be trusted to endure them. The Oyster didn’t create the dive watch; it established belief. That time could be sealed, protected, and carried through hostile conditions without ceremony. Everything that followed would be built on that assumption.

But water is only the beginning. The ocean is not just wet; it is heavy. At sea level, the air presses down on us with the weight of one atmosphere, a gentle, familiar hug. For every ten meters you descend, the sea adds another. By the time you reach the darkness where real work happens, the water is no longer trying to leak in. It is trying to erase structure and reduce precision to wreckage.

The Holeshot: Omega Marine

They were horologists and engineers, these men whose confidence lay in tolerances, seals, and the behaviour of metal under stress. On the edge of Lake Geneva, they prepared an Omega Marine as if it were an apparatus.

Several watches were fixed to rigid poles and weighted lines. Each piece was carefully tested one last time. The first case sealed inside an outer steel shell - check. Crowns locked down - check. Fastenings secure - check. There wasn’t a spectacle to this. No leap into the water. The watches were lowered slowly, deliberately, meter by meter, until the lake took them from sight. Cold closed in. Pressure accumulated. Time passed.

At roughly seventy meters below the surface, where light thins and water becomes insistent rather than passive, the watches were left to endure. This was not a test of splashes or rainstorms, but of sustained force. When they were eventually raised back to the surface, thirty minutes later, the result was expected, if a tad anticlimactic. The watches were still running.

The watches were again tested in laboratory settings for depths up to 135 meters. But to wind them, you had to dismantle the case. They were survivors, but they were not yet soldiers.

The Weapon’s Champion: Panerai Radiomir

By the late 1930s, the Royal Italian Navy had realised that the next naval battle would not be fought by battleships exchanging fire at the horizon, but by individual men riding submersible torpedoes - the Maiale - into the heart of enemy ports. These men, the Incursori, operated in a world of absolute silence and near-total darkness.

They did not want a watch that could merely survive a dunking. They needed a navigation instrument.

Enter Guido Panerai, a Florence-based supplier of high-precision optical equipment. Sights, compasses, and gauges. When the Navy came calling, he turned to the one company that had already solved the problem of a waterproof case: Rolex. Large pocket-watch movements were repurposed, cased in modified Oyster shells, and fitted with welded wire lugs so they could be strapped over thick rubber suits.

But the true innovation was not the case. It was the dial. To read time in the muddy blackness of a Mediterranean harbour, Panerai developed a radium-based luminous compound known as Radiomir. It glowed with a ferocity. It was toxic, dangerous, and brutally effective.

The Radiomirs were not sold in shops. They were controlled items, issued like rifles. And they proved that a watch could be more than a survivor. But they were also large, crude, and narrowly specialised. The dive watch, at this stage, remained heavy artillery - formidable, indispensable, and still waiting to be refined into something more widely usable.

The Blueprint: Blancpain Fifty Fathoms

It took a spy to begin the next chapter. Or rather, a counter-intelligence officer turned combat swimmer: Captain Bob Maloubier.

In 1952, Maloubier and his lieutenant, Claude Riffaud, were tasked with forming the French Navy’s elite diving unit, the Nageurs de Combat. They quickly discovered that their equipment lagged behind their ambition. The watches available either leaked, flooded, or disappeared into illegibility the moment conditions deteriorated.

Maloubier did not want a modified dress watch. He took a pencil and began outlining requirements.

He insisted on a black dial to kill reflections. He demanded oversized luminous indices - circles and rectangles - that could be read by a man dulled by cold, stress, or nitrogen narcosis. But his most consequential demand concerned timing. He wanted a rotating ring that could be aligned with the minute hand at the start of a dive, a simple mechanical reference that answered the only question that mattered: how much longer my air would last?

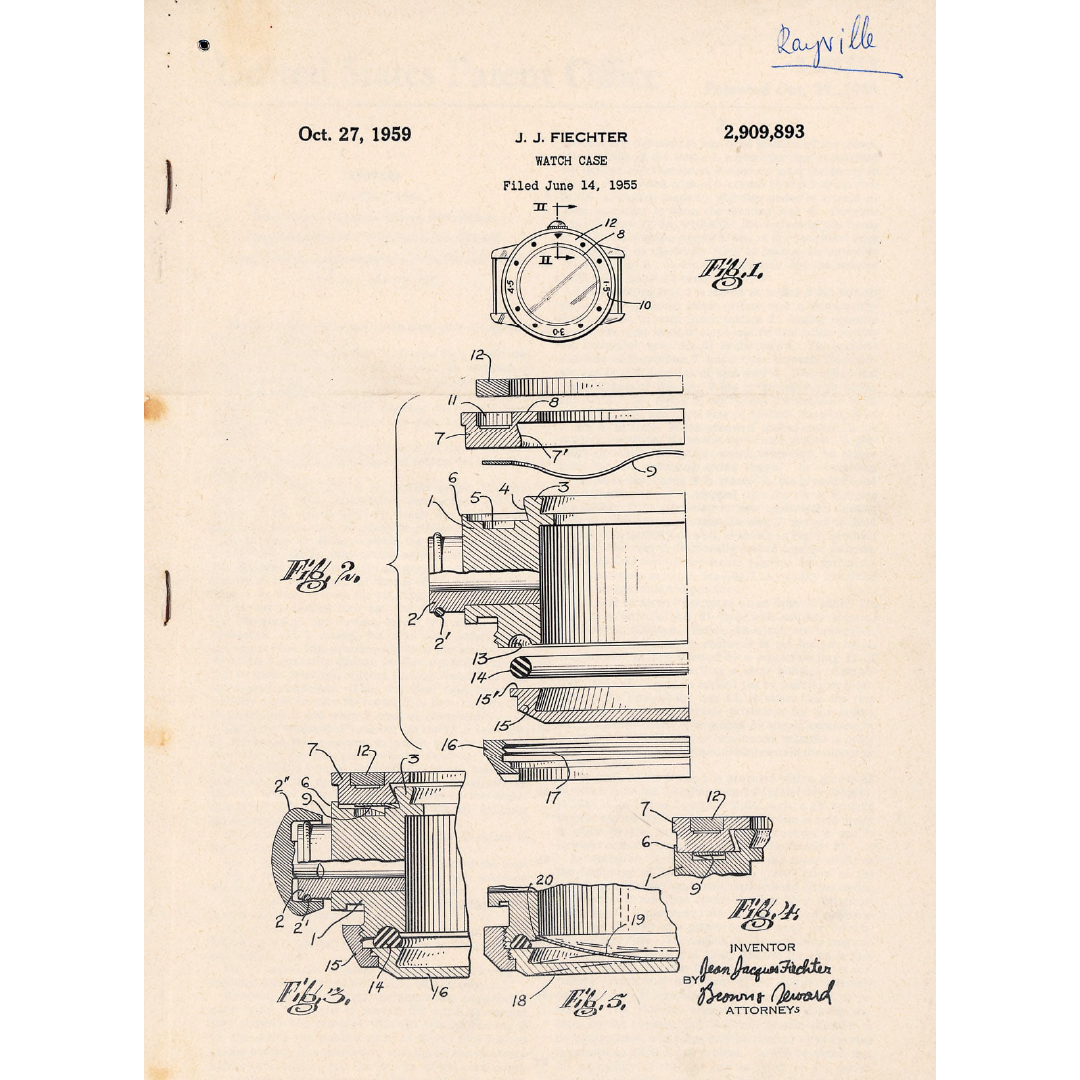

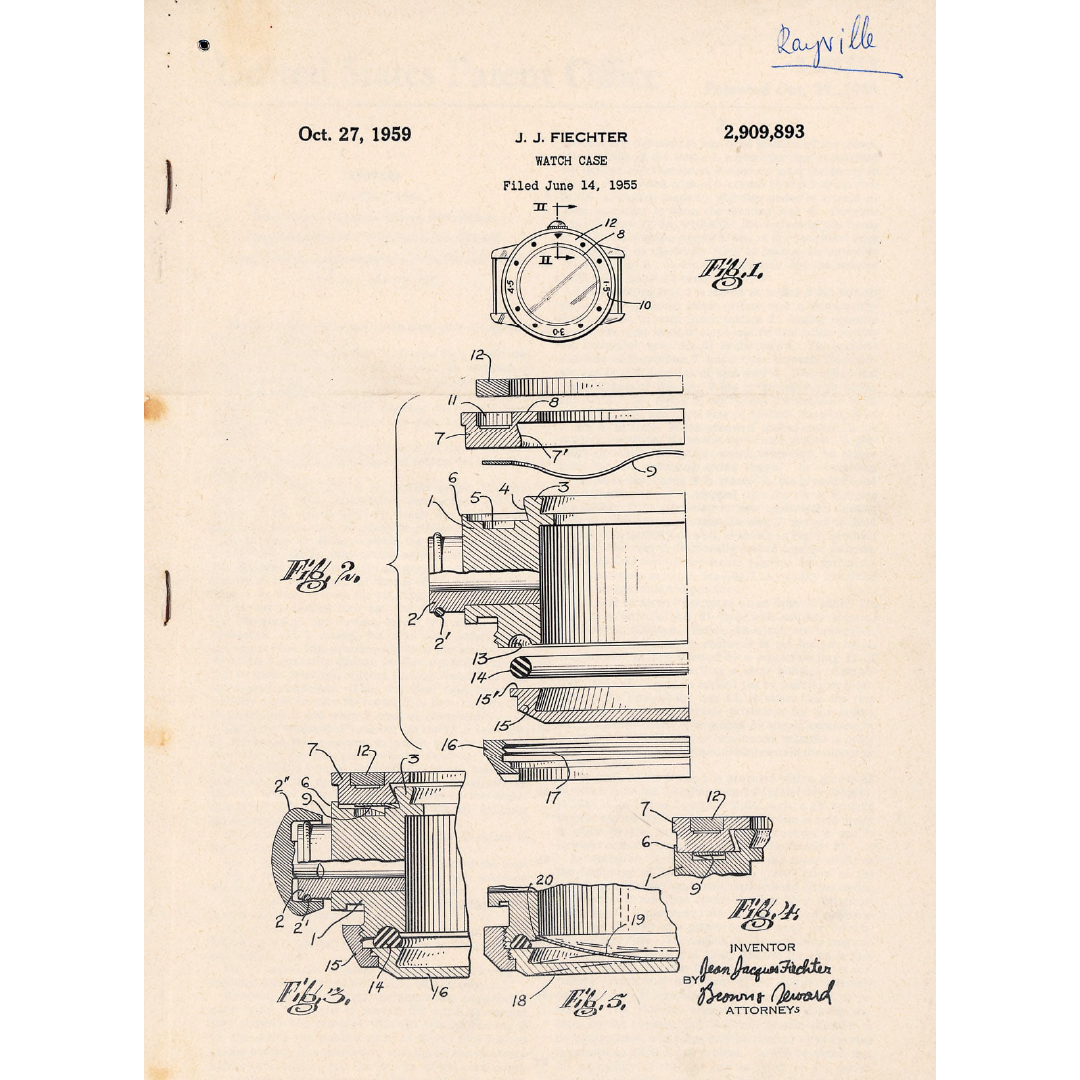

By the early 1950s, several manufacturers were thinking through the same problem in parallel. Blancpain, under Jean-Jacques Fiechter, a diver himself, was simply the first to resolve those demands into a coherent, wearable form.

They called the watch the Fifty Fathoms.

When it arrived in 1953, the argument was settled. The essential elements were in place: legibility, timing, redundancy, and restraint. The dive watch had ceased to be an experiment or a weapon and had become something more coherent. The blueprint had been drawn. The lifesaver had a face.

The Archetype: Rolex Ref. 6204

If Blancpain wrote the song, Rolex turned it into the anthem.

The same year, at the Basel Fair, Rolex unveiled the Reference 6204. It was immediately recognisable as kin to the Fifty Fathoms. Same bloodline, different voice. Where Blancpain spoke in the language of professional necessity, Rolex chose something more fluent, more worldly. This was a sports watch. Serious, capable, and unafraid of salt and pressure, yet perfectly at ease once the wetsuit was peeled away and the day resumed on land.

The Reference 6204 or the Submariner (some early examples also had the word Sub-Aqua on their dials) belonged unmistakably to the post-war optimism of the 1950s, and its French inflexion mattered. The hinge figure was René-Paul Jeanneret. A close friend of Jacques-Yves Cousteau (the inventor of Aqua-Lung, and by extension recreational diving as a sport), and a committed underwater explorer in his own right, Jeanneret also sat on the Rolex board. He is credited with articulating the idea of a watch that could move effortlessly from sea to street, from tool to companion. In convincing the other directors, he did more than define a product. He widened the aperture through which Rolex would be seen.

After the Submariner, change became a matter of increments rather than ideology. Depth ratings edged higher. Cases thickened, then slimmed again. Materials appeared, disappeared, and returned, wearing new justifications. Yet the silhouette endured.

Other solutions for diving watches did emerge, tentative deviations at the margins, but they never gathered enough force to redirect the flow.

To be continued…

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

The English Channel in October is less a body of water and more a particularly vindictive slab of granite. So did Mercedes Gleitze, though her knowledge came the hard way. The announcement of her successful crossing, however, was not made breathlessly from the shore, nor shouted hoarse in triumph. It arrived instead as a full-page advertisement in the Daily Mail.

What mattered wasn’t whether the watch had conquered the elements - nature has a habit of correcting that language - but that, for the first time, a wristwatch could be trusted to endure them. The Oyster didn’t create the dive watch; it established belief. That time could be sealed, protected, and carried through hostile conditions without ceremony. Everything that followed would be built on that assumption.

But water is only the beginning. The ocean is not just wet; it is heavy. At sea level, the air presses down on us with the weight of one atmosphere, a gentle, familiar hug. For every ten meters you descend, the sea adds another. By the time you reach the darkness where real work happens, the water is no longer trying to leak in. It is trying to erase structure and reduce precision to wreckage.

The Holeshot: Omega Marine

They were horologists and engineers, these men whose confidence lay in tolerances, seals, and the behaviour of metal under stress. On the edge of Lake Geneva, they prepared an Omega Marine as if it were an apparatus.

Several watches were fixed to rigid poles and weighted lines. Each piece was carefully tested one last time. The first case sealed inside an outer steel shell - check. Crowns locked down - check. Fastenings secure - check. There wasn’t a spectacle to this. No leap into the water. The watches were lowered slowly, deliberately, meter by meter, until the lake took them from sight. Cold closed in. Pressure accumulated. Time passed.

At roughly seventy meters below the surface, where light thins and water becomes insistent rather than passive, the watches were left to endure. This was not a test of splashes or rainstorms, but of sustained force. When they were eventually raised back to the surface, thirty minutes later, the result was expected, if a tad anticlimactic. The watches were still running.

The watches were again tested in laboratory settings for depths up to 135 meters. But to wind them, you had to dismantle the case. They were survivors, but they were not yet soldiers.

The Weapon’s Champion: Panerai Radiomir

By the late 1930s, the Royal Italian Navy had realised that the next naval battle would not be fought by battleships exchanging fire at the horizon, but by individual men riding submersible torpedoes - the Maiale - into the heart of enemy ports. These men, the Incursori, operated in a world of absolute silence and near-total darkness.

They did not want a watch that could merely survive a dunking. They needed a navigation instrument.

Enter Guido Panerai, a Florence-based supplier of high-precision optical equipment. Sights, compasses, and gauges. When the Navy came calling, he turned to the one company that had already solved the problem of a waterproof case: Rolex. Large pocket-watch movements were repurposed, cased in modified Oyster shells, and fitted with welded wire lugs so they could be strapped over thick rubber suits.

But the true innovation was not the case. It was the dial. To read time in the muddy blackness of a Mediterranean harbour, Panerai developed a radium-based luminous compound known as Radiomir. It glowed with a ferocity. It was toxic, dangerous, and brutally effective.

The Radiomirs were not sold in shops. They were controlled items, issued like rifles. And they proved that a watch could be more than a survivor. But they were also large, crude, and narrowly specialised. The dive watch, at this stage, remained heavy artillery - formidable, indispensable, and still waiting to be refined into something more widely usable.

The Blueprint: Blancpain Fifty Fathoms

It took a spy to begin the next chapter. Or rather, a counter-intelligence officer turned combat swimmer: Captain Bob Maloubier.

In 1952, Maloubier and his lieutenant, Claude Riffaud, were tasked with forming the French Navy’s elite diving unit, the Nageurs de Combat. They quickly discovered that their equipment lagged behind their ambition. The watches available either leaked, flooded, or disappeared into illegibility the moment conditions deteriorated.

Maloubier did not want a modified dress watch. He took a pencil and began outlining requirements.

He insisted on a black dial to kill reflections. He demanded oversized luminous indices - circles and rectangles - that could be read by a man dulled by cold, stress, or nitrogen narcosis. But his most consequential demand concerned timing. He wanted a rotating ring that could be aligned with the minute hand at the start of a dive, a simple mechanical reference that answered the only question that mattered: how much longer my air would last?

By the early 1950s, several manufacturers were thinking through the same problem in parallel. Blancpain, under Jean-Jacques Fiechter, a diver himself, was simply the first to resolve those demands into a coherent, wearable form.

They called the watch the Fifty Fathoms.

When it arrived in 1953, the argument was settled. The essential elements were in place: legibility, timing, redundancy, and restraint. The dive watch had ceased to be an experiment or a weapon and had become something more coherent. The blueprint had been drawn. The lifesaver had a face.

The Archetype: Rolex Ref. 6204

If Blancpain wrote the song, Rolex turned it into the anthem.

The same year, at the Basel Fair, Rolex unveiled the Reference 6204. It was immediately recognisable as kin to the Fifty Fathoms. Same bloodline, different voice. Where Blancpain spoke in the language of professional necessity, Rolex chose something more fluent, more worldly. This was a sports watch. Serious, capable, and unafraid of salt and pressure, yet perfectly at ease once the wetsuit was peeled away and the day resumed on land.

The Reference 6204 or the Submariner (some early examples also had the word Sub-Aqua on their dials) belonged unmistakably to the post-war optimism of the 1950s, and its French inflexion mattered. The hinge figure was René-Paul Jeanneret. A close friend of Jacques-Yves Cousteau (the inventor of Aqua-Lung, and by extension recreational diving as a sport), and a committed underwater explorer in his own right, Jeanneret also sat on the Rolex board. He is credited with articulating the idea of a watch that could move effortlessly from sea to street, from tool to companion. In convincing the other directors, he did more than define a product. He widened the aperture through which Rolex would be seen.

After the Submariner, change became a matter of increments rather than ideology. Depth ratings edged higher. Cases thickened, then slimmed again. Materials appeared, disappeared, and returned, wearing new justifications. Yet the silhouette endured.

Other solutions for diving watches did emerge, tentative deviations at the margins, but they never gathered enough force to redirect the flow.

To be continued…