Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

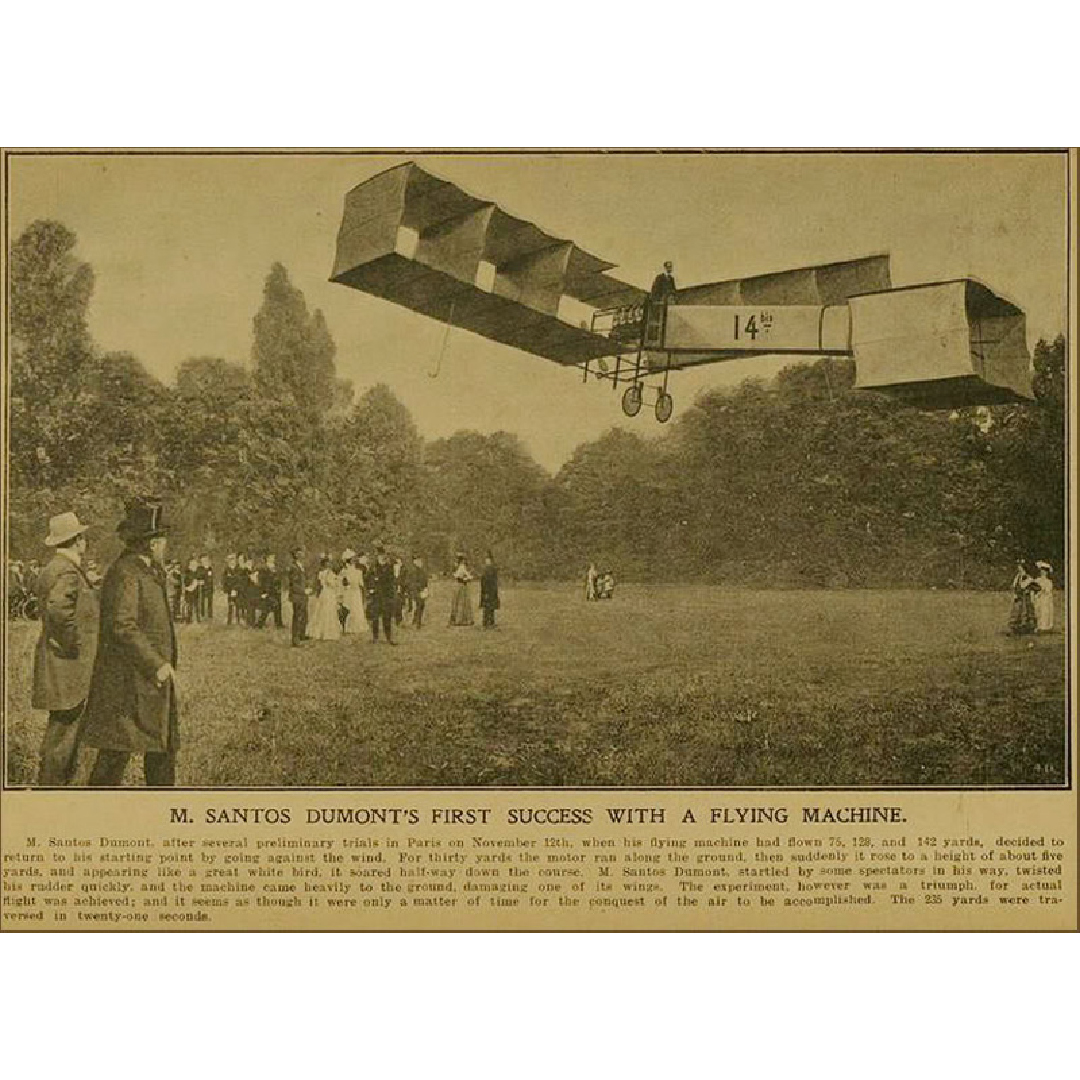

The cold in the trench had a texture. It crept under collars, made itself home in boots, and carried the faint metallic tang of iron, cordite, and disappointment. For Private John Harwood — watchmaker, reluctant soldier, and part-time philosopher of futility — it was also a design problem masquerading as nature.

He watched the man beside him, eyes dull in the dark, fumbling with his pocket-turned-wrist-watch like it held the secret to going home. The soldier’s fingers were blue and mutinous, struggling with the tiny knurled crown that gave the machine its daily breath. Every twist felt like an act of faith. As if order could still be wound into chaos, that a schedule could outlast artillery. In that sodden absurdity, even time seemed embarrassed to be ticking.

The watch had no idea what it had signed up for. It was a creature of parlours and waistcoats, now knee-deep in the end of civilization, trying to look brave. A dandy in a trench. Harwood suspected it missed the sound of teaspoons.

The flaw wasn’t in the metal or the strap. It was in the ritual. A watch that needed to be hand-fed each morning was as deluded as the men who thought this war could be managed by timetables. Winding it felt almost indecent, like insisting on etiquette at a hanging.

While other men dreamed of home, Harwood dreamed of mechanisms. Of self-sufficiency, of cogs that didn’t beg for attention. The war had taught him that habits die faster than soldiers, and that dependence, whether on kings, clocks, or causes, was the first casualty worth celebrating.

So somewhere between mud and morning, he made a quiet promise to himself. The crown would have to go. Not out of defiance, but out of a deep, mechanical pity for everything that still needed winding.

The Playground on the Isle

When the war ended and Harwood returned to his bench on the Isle of Man, he soldiered on, though this time, his campaign was fought in silence. Drafts of blueprints had replaced the trenches, and the only explosions now were ideas.

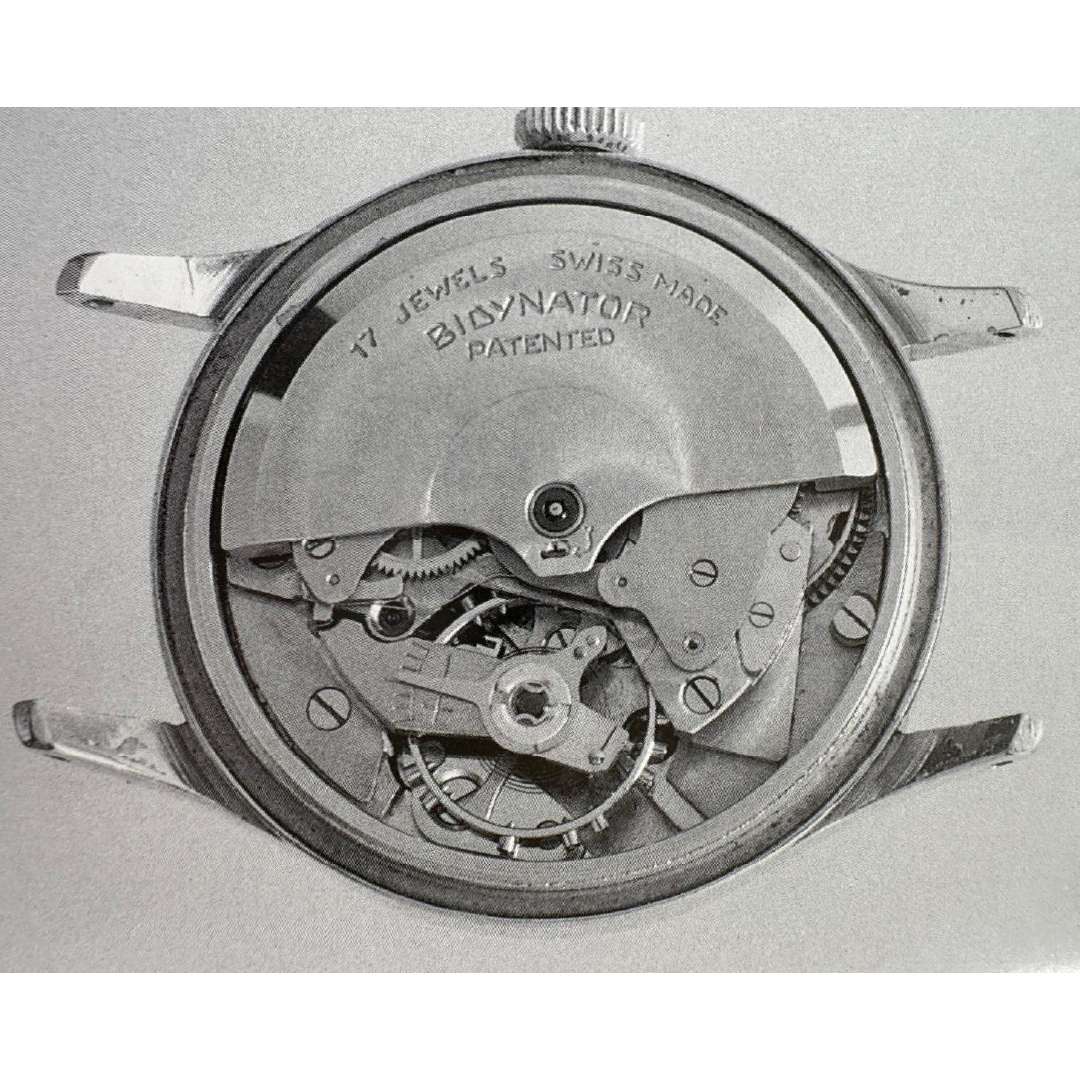

Legend says the thought came to him while watching a child on a see-saw, a small weight transferring motion into rhythm. Balance turning into continuity. Harwood borrowed that physics for his own kind of salvation. He added a semicircular weight to the watch’s mechanism. One that swung with the movement of the wrist. Each tilt of an arm, a handshake, a reach for a glass, the dignified act of lighting a pipe, nudged the mainspring a little tighter. The watch, for the first time, began to feed itself. A small mechanical species had learned the art of self-reliance.

But Harwood wasn’t done. Winding was only half the servitude. Setting the time still required that treacherous little portal called the crown. He’d seen enough crowns to last a lifetime. So he abolished it. He coupled the setting mechanism to the bezel; turning the outer ring now adjusted the hands. No puncture, no compromise, no small daily humiliation. What he built was a fortress without doors. A sealed world of gears and grace, immune to mud, moisture, and meddling.

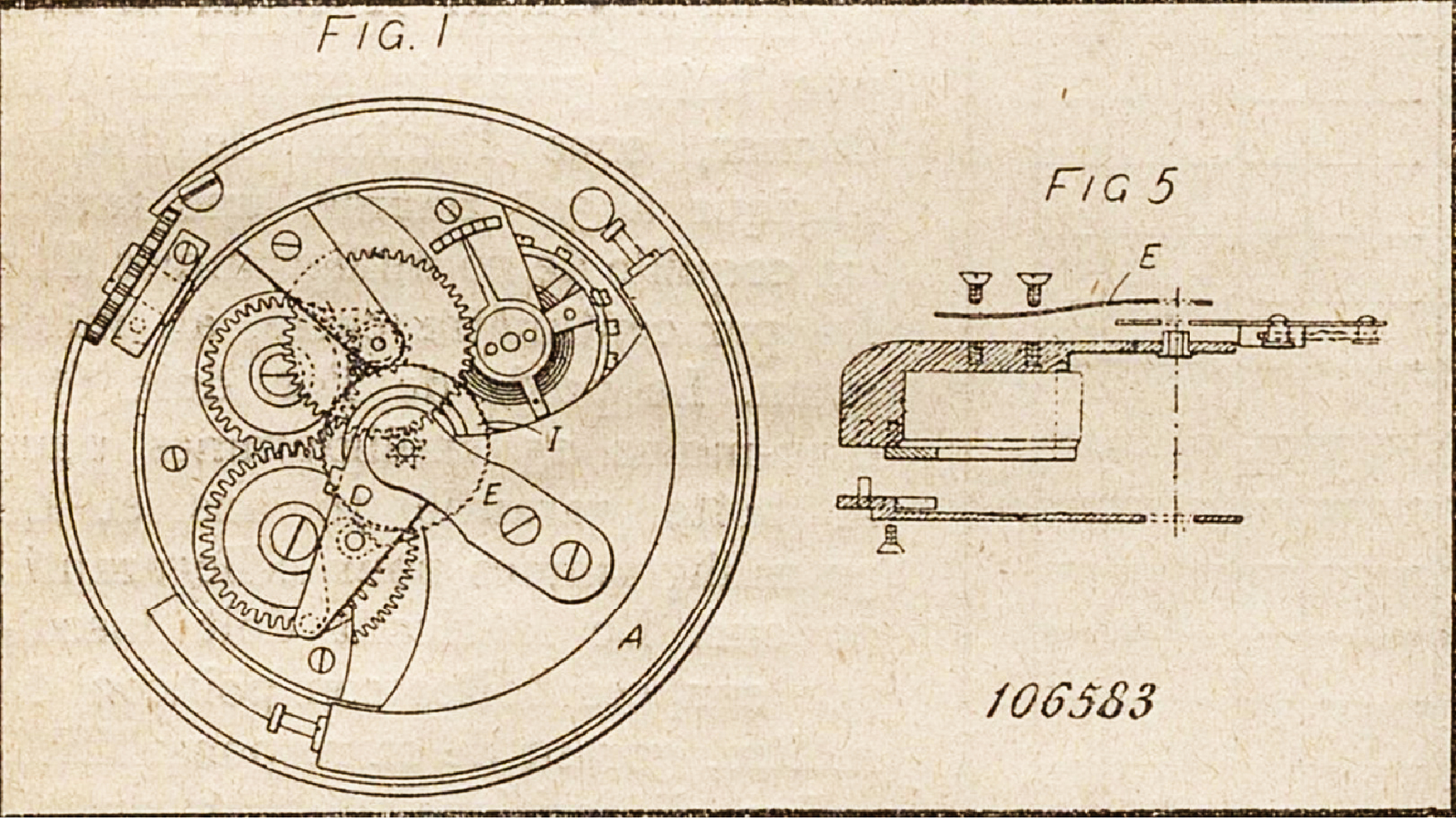

In 1923, he filed the patent, and the first self-winding wristwatch was born. A watch that lived on motion, a miniature republic powered by life itself.

Harwood gave the watch independence, and in doing so, gave time a touch of irony. For, in seeking to master it, he’d taught it to move on its own.

From a Bump to a Revolution

Harwood’s ‘bumper’ automatic was ingenious, but it carried the polite awkwardness of a prototype. The sort of contraption that coughed before it spoke. The rotor’s short arc worked admirably, provided life was suitably eventful. A soldier’s salute could wind it, but an accountant’s day would not. It was a watch that thrived on chaos and dozed politely through meetings.

Mechanically, it was also a touch temperamental. A see-saw with opinions. Springs sulked, screws loosened, and the motion had the overeager charm of an apprentice trying too hard. Still, the principle was sound. Profound, even. For the first time, time took its cue from life itself. It no longer relied on that small daily ceremony, the bead-rolling ritual of thumb and forefinger, winding obedience into order. Time had begun to march, or rather amble, to a human rhythm.

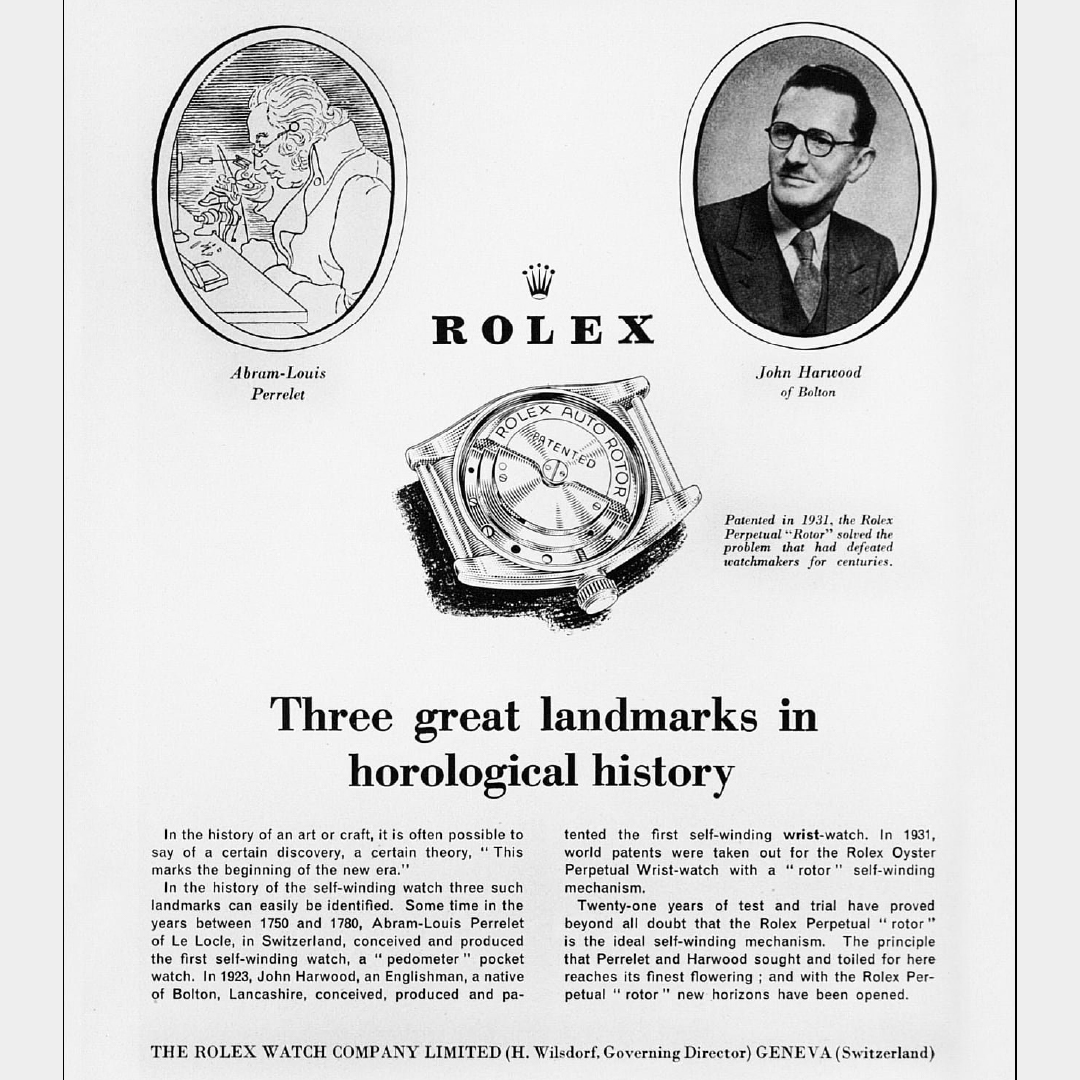

Then, inevitably, Hans Wilsdorf noticed. Wilsdorf, ever the evangelist of precision, had already locked the world out with his Oyster — a waterproof fortress for the wrist — but his so-called ‘perpetual’ dream still spoke in fluent irony. You still had to unscrew the crown each morning to wind it.

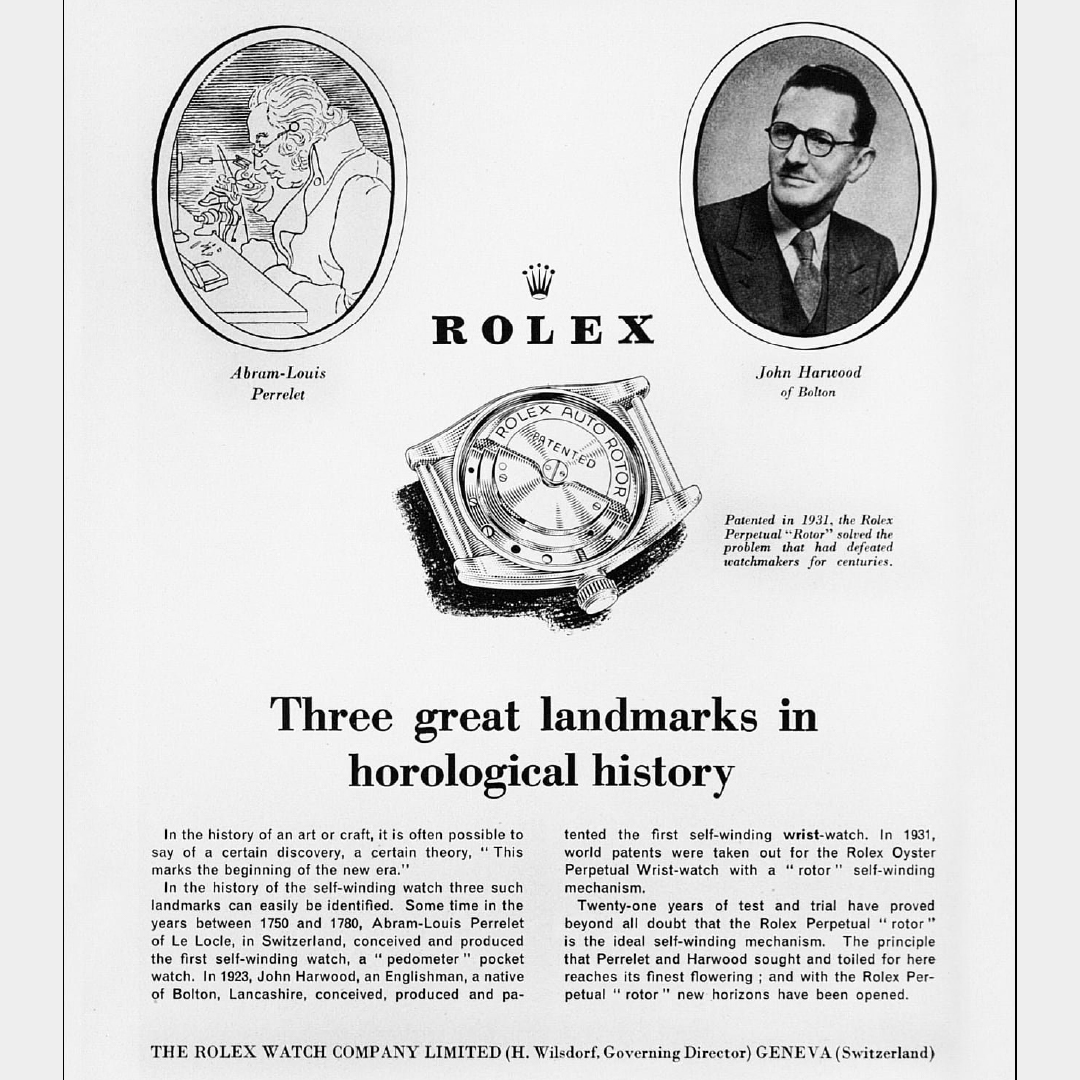

And so Wilsdorf borrowed the idea of autonomy from Harwood, and in 1931, Rolex unveiled the Perpetual movement, the quiet miracle that replaced Harwood’s bump with a glide. The rotor could now spin a full 360 degrees, capturing even the smallest gesture. A steering wheel turned, a glass lifted, a wave. It turned grace itself into energy.

The mechanism was silent, assured, almost smug. Together with the Oyster case, it completed the circle. Sealed, self-sustaining, and serenely indifferent to the outside world.

The watch no longer needed tending. It merely needed to be lived in.

The Inheritance of Motion

The idea caught on, as most good ideas do. Quietly, then all at once. By the mid-1930s, Harwood’s ghost and Wilsdorf’s refinement had gone wandering through the valleys of Switzerland, gathering disciples in their wake.

Omega, Longines, and Jaeger-LeCoultre all took turns reinventing the wheel, each politely pretending it was their own while secretly tipping a hat to the man who had first given it motion. Even the smaller houses joined in, fitting bumpers and rotors into cases meant for offices, factories, and cocktail hours alike.

The self-winding movement stopped being an innovation and became an instinct, the horological equivalent of breathing or gossip. A watch that didn’t wind itself now felt oddly needy, a relic of a more strenuous age.

By the time the decade turned, the act of winding a watch had begun to feel quaint. An affectation, like heating water over a candle. A small daily intimacy with time that progress, in its enthusiasm, had quietly filed away.

The Migration is Complete

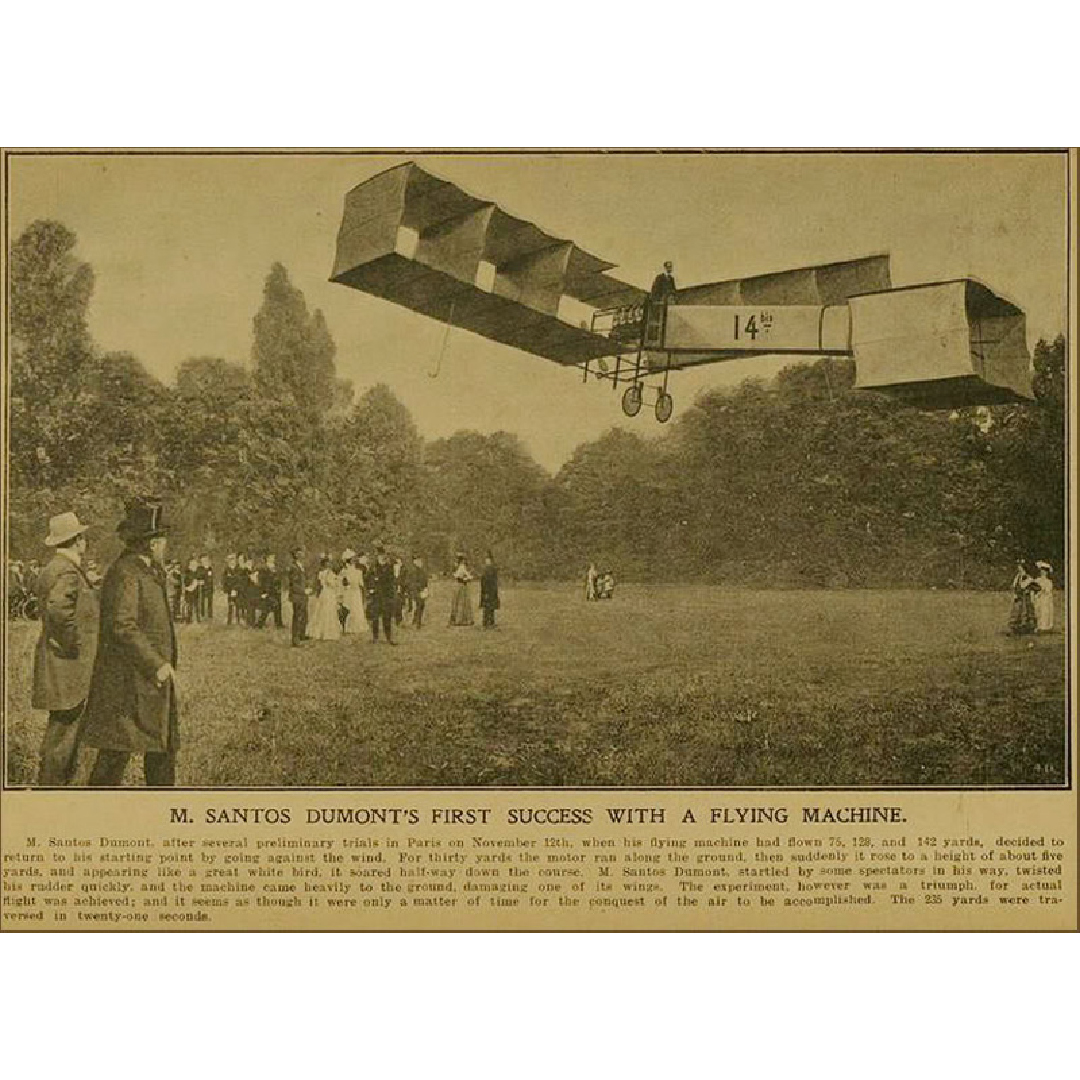

It had begun in panic. Time fleeing the pocket for the wrist, abandoning discretion for command. It learned vanity in the mirrored glass of Paris, endurance in the rain over the Channel, and, at last, independence in the quiet hum of a rotor.

The watch had survived war, fashion, and the weathering of purpose. It had learned to breathe on its own. A small mechanical creature that no longer waited to be awakened by touch. For the first time, man and machine were equals. Each moving, each keeping the other alive.

But independence is never without irony. Once the watch no longer needed winding, it also stopped needing reassurance. The nightly gesture, the turning between finger and thumb, that tiny domestic tenderness, vanished without ceremony.

The servant had learned freedom; the master, perhaps, a little loss. And yet, every glance at the wrist still renews the same old truce forged in mud and motion.

In this final drift, the great migration had found its still point.

It sits quietly now. Sealed, perpetual, and perfectly self-possessed. Waiting, as it always does, for mankind to catch up.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

The cold in the trench had a texture. It crept under collars, made itself home in boots, and carried the faint metallic tang of iron, cordite, and disappointment. For Private John Harwood — watchmaker, reluctant soldier, and part-time philosopher of futility — it was also a design problem masquerading as nature.

He watched the man beside him, eyes dull in the dark, fumbling with his pocket-turned-wrist-watch like it held the secret to going home. The soldier’s fingers were blue and mutinous, struggling with the tiny knurled crown that gave the machine its daily breath. Every twist felt like an act of faith. As if order could still be wound into chaos, that a schedule could outlast artillery. In that sodden absurdity, even time seemed embarrassed to be ticking.

The watch had no idea what it had signed up for. It was a creature of parlours and waistcoats, now knee-deep in the end of civilization, trying to look brave. A dandy in a trench. Harwood suspected it missed the sound of teaspoons.

The flaw wasn’t in the metal or the strap. It was in the ritual. A watch that needed to be hand-fed each morning was as deluded as the men who thought this war could be managed by timetables. Winding it felt almost indecent, like insisting on etiquette at a hanging.

While other men dreamed of home, Harwood dreamed of mechanisms. Of self-sufficiency, of cogs that didn’t beg for attention. The war had taught him that habits die faster than soldiers, and that dependence, whether on kings, clocks, or causes, was the first casualty worth celebrating.

So somewhere between mud and morning, he made a quiet promise to himself. The crown would have to go. Not out of defiance, but out of a deep, mechanical pity for everything that still needed winding.

The Playground on the Isle

When the war ended and Harwood returned to his bench on the Isle of Man, he soldiered on, though this time, his campaign was fought in silence. Drafts of blueprints had replaced the trenches, and the only explosions now were ideas.

Legend says the thought came to him while watching a child on a see-saw, a small weight transferring motion into rhythm. Balance turning into continuity. Harwood borrowed that physics for his own kind of salvation. He added a semicircular weight to the watch’s mechanism. One that swung with the movement of the wrist. Each tilt of an arm, a handshake, a reach for a glass, the dignified act of lighting a pipe, nudged the mainspring a little tighter. The watch, for the first time, began to feed itself. A small mechanical species had learned the art of self-reliance.

But Harwood wasn’t done. Winding was only half the servitude. Setting the time still required that treacherous little portal called the crown. He’d seen enough crowns to last a lifetime. So he abolished it. He coupled the setting mechanism to the bezel; turning the outer ring now adjusted the hands. No puncture, no compromise, no small daily humiliation. What he built was a fortress without doors. A sealed world of gears and grace, immune to mud, moisture, and meddling.

In 1923, he filed the patent, and the first self-winding wristwatch was born. A watch that lived on motion, a miniature republic powered by life itself.

Harwood gave the watch independence, and in doing so, gave time a touch of irony. For, in seeking to master it, he’d taught it to move on its own.

From a Bump to a Revolution

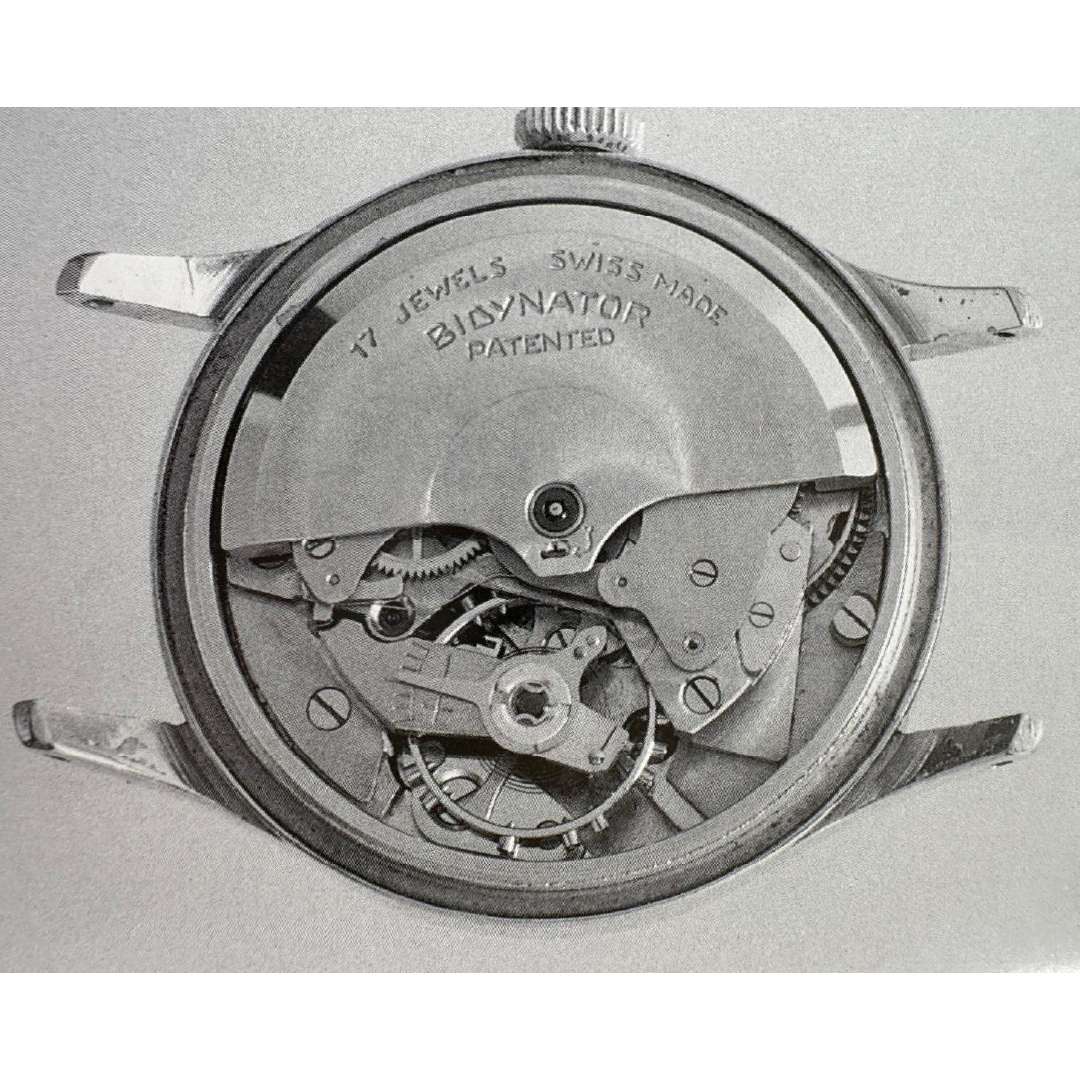

Harwood’s ‘bumper’ automatic was ingenious, but it carried the polite awkwardness of a prototype. The sort of contraption that coughed before it spoke. The rotor’s short arc worked admirably, provided life was suitably eventful. A soldier’s salute could wind it, but an accountant’s day would not. It was a watch that thrived on chaos and dozed politely through meetings.

Mechanically, it was also a touch temperamental. A see-saw with opinions. Springs sulked, screws loosened, and the motion had the overeager charm of an apprentice trying too hard. Still, the principle was sound. Profound, even. For the first time, time took its cue from life itself. It no longer relied on that small daily ceremony, the bead-rolling ritual of thumb and forefinger, winding obedience into order. Time had begun to march, or rather amble, to a human rhythm.

Then, inevitably, Hans Wilsdorf noticed. Wilsdorf, ever the evangelist of precision, had already locked the world out with his Oyster — a waterproof fortress for the wrist — but his so-called ‘perpetual’ dream still spoke in fluent irony. You still had to unscrew the crown each morning to wind it.

And so Wilsdorf borrowed the idea of autonomy from Harwood, and in 1931, Rolex unveiled the Perpetual movement, the quiet miracle that replaced Harwood’s bump with a glide. The rotor could now spin a full 360 degrees, capturing even the smallest gesture. A steering wheel turned, a glass lifted, a wave. It turned grace itself into energy.

The mechanism was silent, assured, almost smug. Together with the Oyster case, it completed the circle. Sealed, self-sustaining, and serenely indifferent to the outside world.

The watch no longer needed tending. It merely needed to be lived in.

The Inheritance of Motion

The idea caught on, as most good ideas do. Quietly, then all at once. By the mid-1930s, Harwood’s ghost and Wilsdorf’s refinement had gone wandering through the valleys of Switzerland, gathering disciples in their wake.

Omega, Longines, and Jaeger-LeCoultre all took turns reinventing the wheel, each politely pretending it was their own while secretly tipping a hat to the man who had first given it motion. Even the smaller houses joined in, fitting bumpers and rotors into cases meant for offices, factories, and cocktail hours alike.

The self-winding movement stopped being an innovation and became an instinct, the horological equivalent of breathing or gossip. A watch that didn’t wind itself now felt oddly needy, a relic of a more strenuous age.

By the time the decade turned, the act of winding a watch had begun to feel quaint. An affectation, like heating water over a candle. A small daily intimacy with time that progress, in its enthusiasm, had quietly filed away.

The Migration is Complete

It had begun in panic. Time fleeing the pocket for the wrist, abandoning discretion for command. It learned vanity in the mirrored glass of Paris, endurance in the rain over the Channel, and, at last, independence in the quiet hum of a rotor.

The watch had survived war, fashion, and the weathering of purpose. It had learned to breathe on its own. A small mechanical creature that no longer waited to be awakened by touch. For the first time, man and machine were equals. Each moving, each keeping the other alive.

But independence is never without irony. Once the watch no longer needed winding, it also stopped needing reassurance. The nightly gesture, the turning between finger and thumb, that tiny domestic tenderness, vanished without ceremony.

The servant had learned freedom; the master, perhaps, a little loss. And yet, every glance at the wrist still renews the same old truce forged in mud and motion.

In this final drift, the great migration had found its still point.

It sits quietly now. Sealed, perpetual, and perfectly self-possessed. Waiting, as it always does, for mankind to catch up.