Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

Paris 1901. A cigar-shaped balloon looped the Eiffel Tower while the city squinted upward. Ropes, gas, and a small engine combined to look like confidence, provided you didn’t stare too closely. Alberto Santos-Dumont circled the iron lattice and landed cleanly. Cleanly enough, at least. The stopwatch disagreed, ticking just over the limit.

The officials looked pained. Rules are rules after all. But Paris, being Paris, applauded as if being tardy were part of the charm. Eventually, the timekeepers began to feel they were the impolite ones.

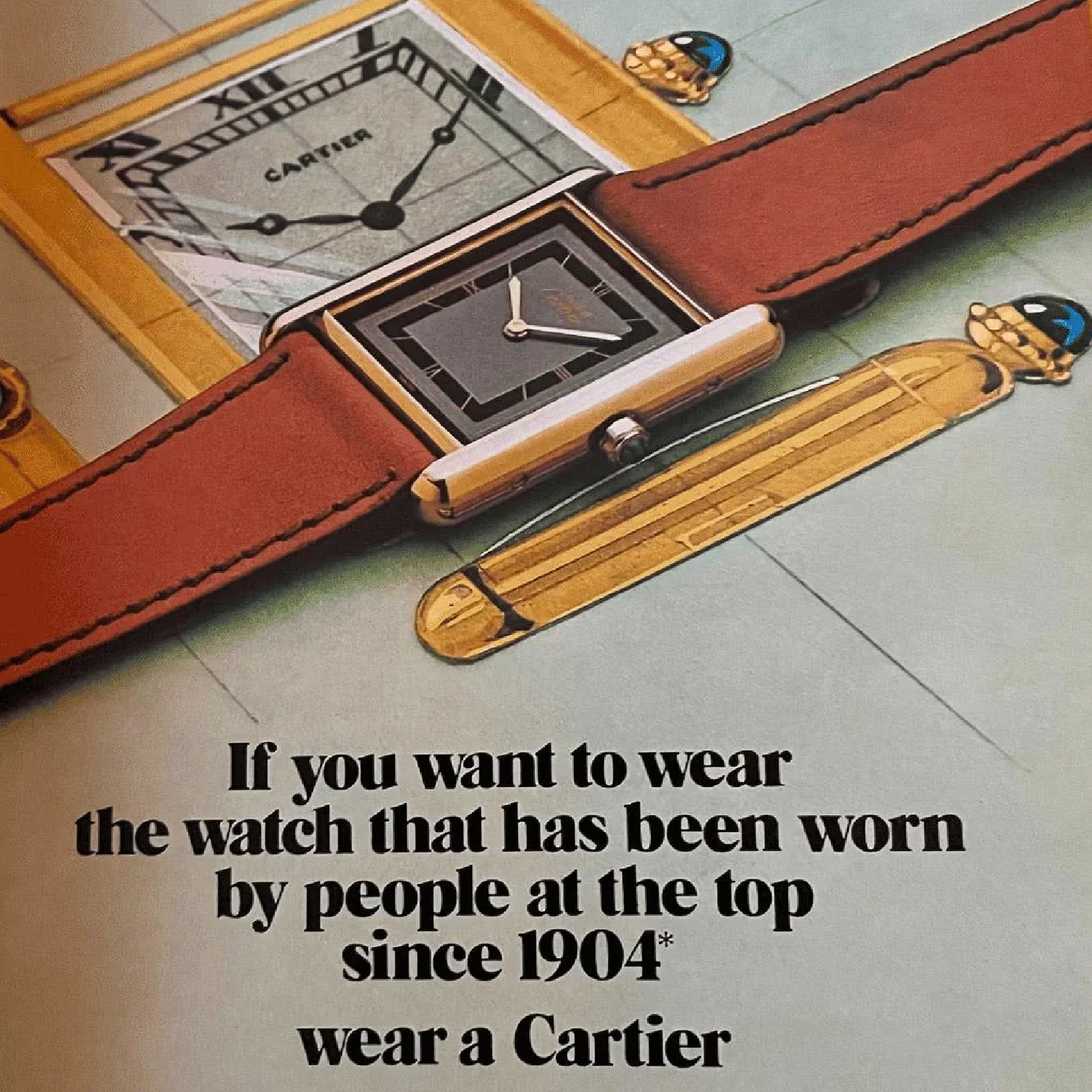

A few days later, the Deutsch Prize found its winner, as it always meant to. That night, there was a table, a bottle, and two men who like problems. Santos-Dumont taps his waistcoat. “Up there, I fly with one hand and fish for time with the other. It’s foolish.” Louis Cartier listens, then sketches a square that won’t roll, a dial that reads at a glance, and a crown your fingers would find without thinking.

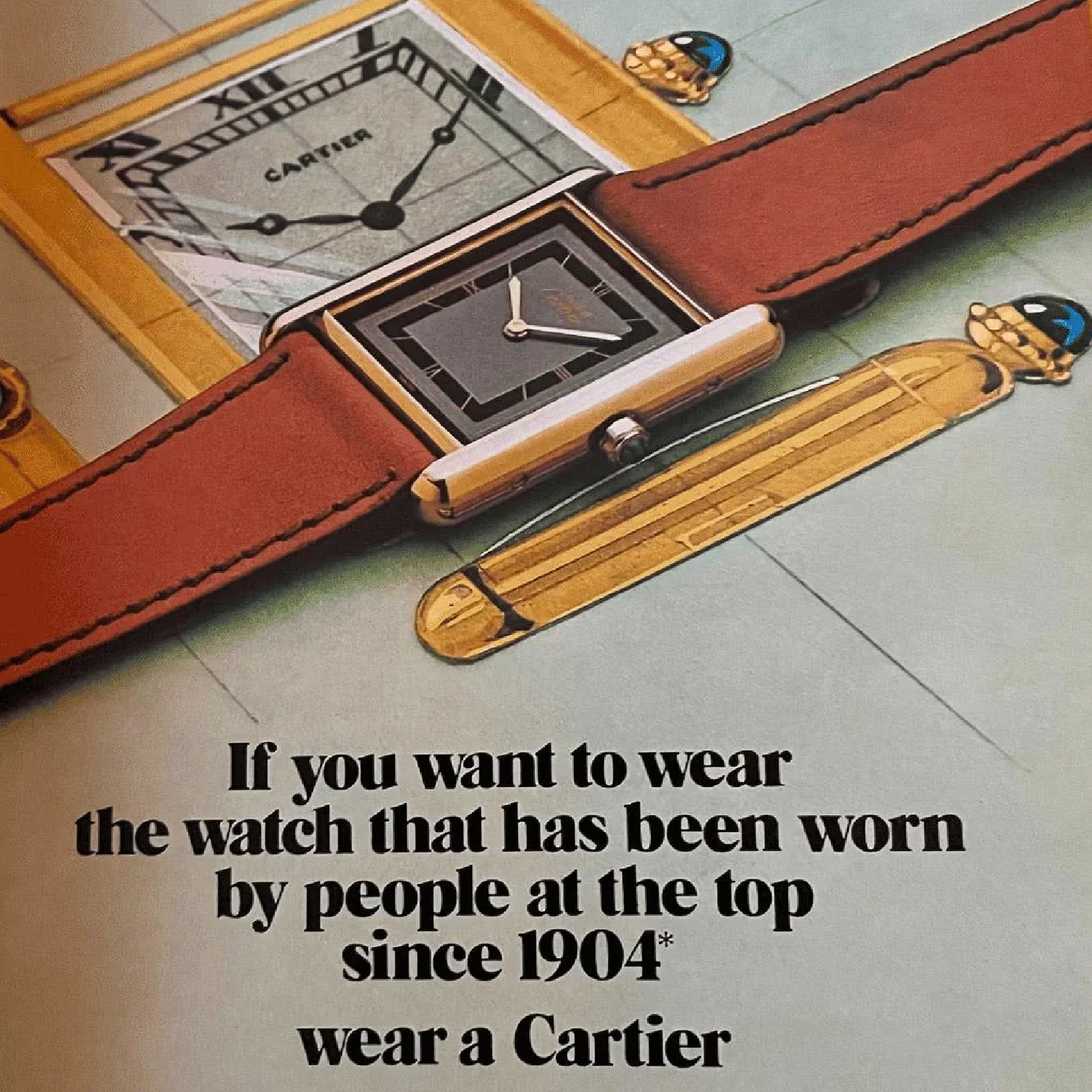

In 1904, the Cartier Santos arrived. It was among the first purpose-built wristwatches for men. A pilot’s gripe turned into a solution, and a fashion statement nobody had asked for but would eventually pretend they had always wanted.

An Invention Nobody Asked For

Cartier’s new square on a strap was less an invention, more a polite suggestion in a language no one wanted to learn. The world, still in love with its chains, gave him the sort of look usually reserved for avant-garde painters and people who ordered salads in steak houses.

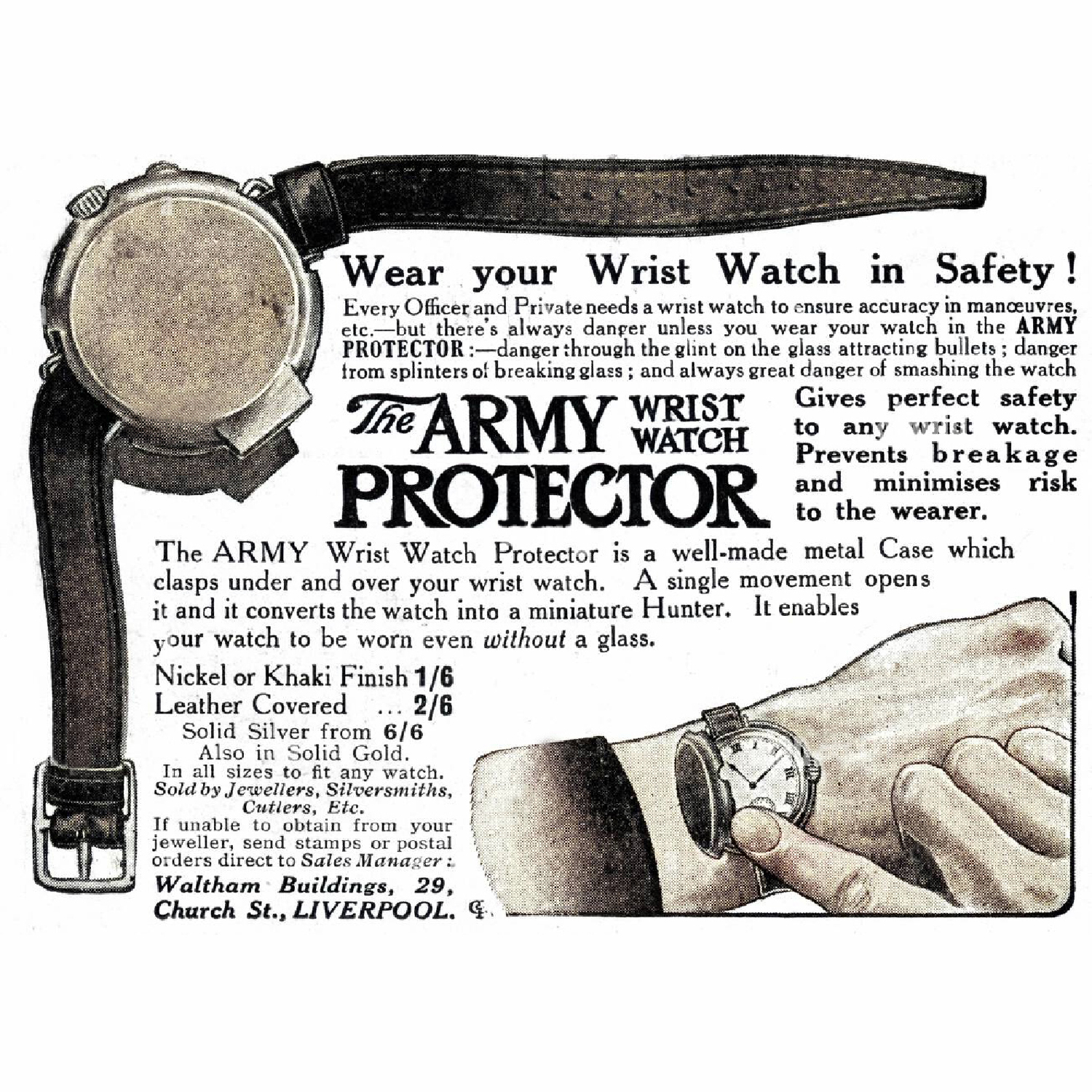

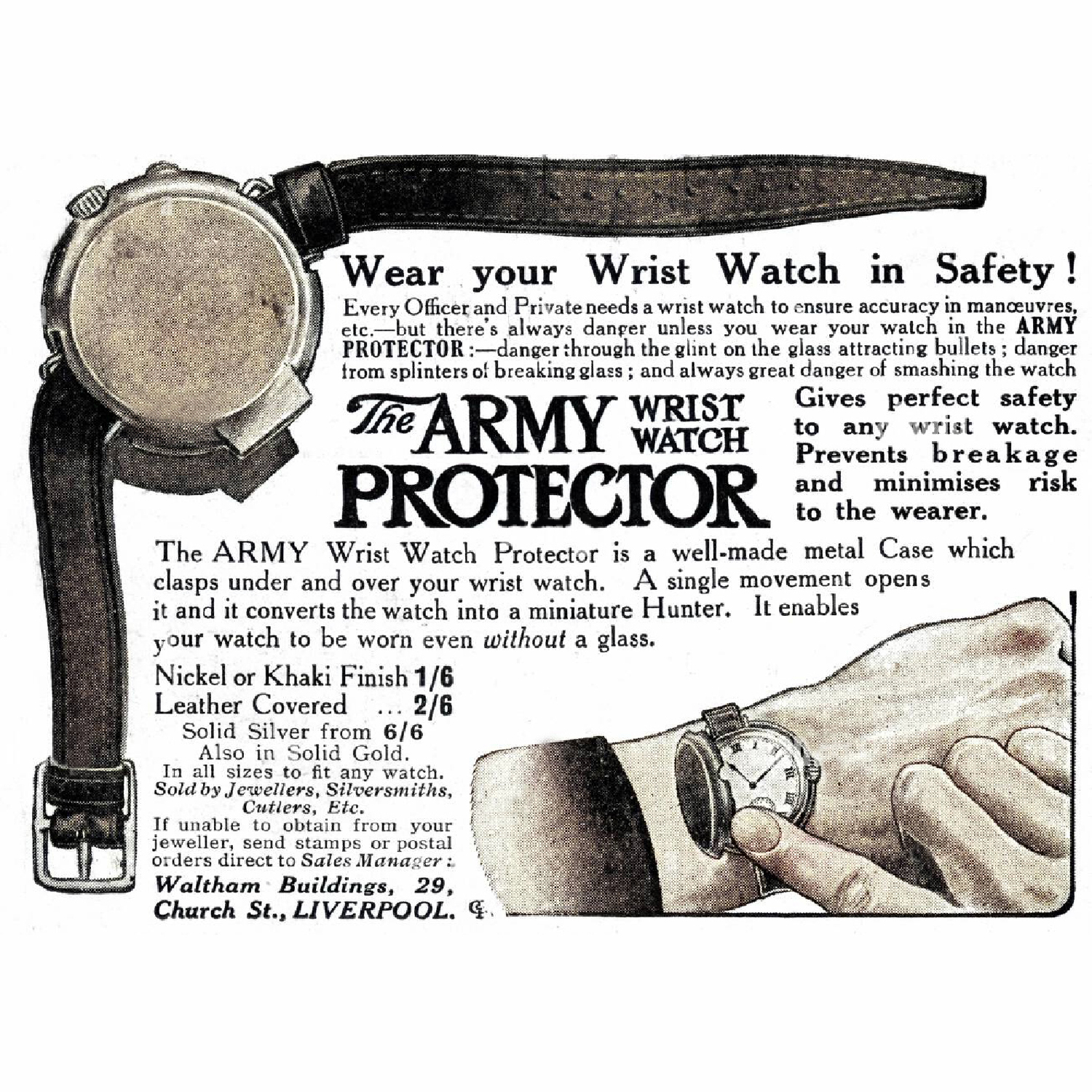

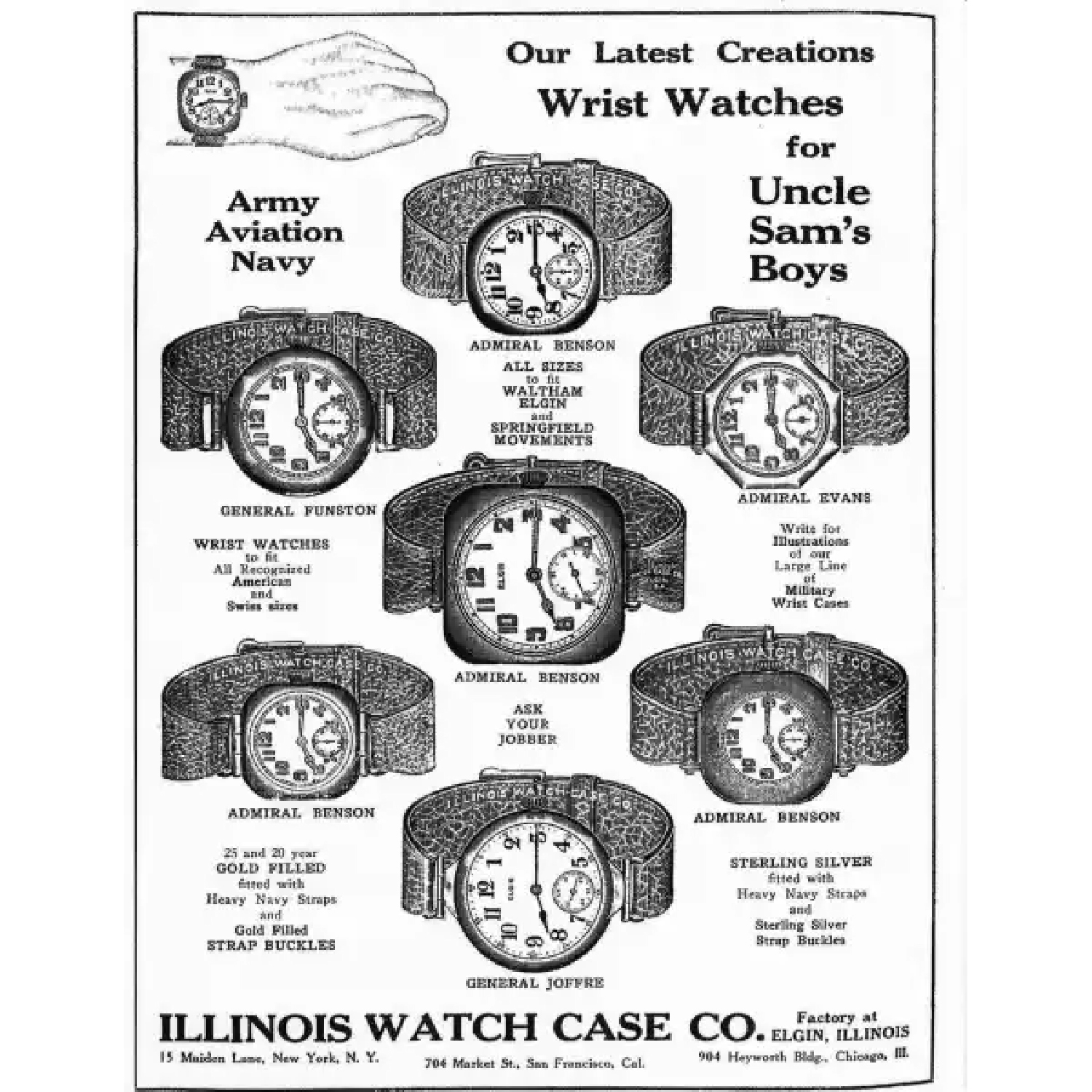

It took a war to settle the argument — a very large, very loud one. By the time it ended, men stepped off trains thinner, quieter, and with no appetite for patting down their pockets in search of time. The paperwork of peace took longer than anyone had promised, and it had also delivered a final, brutal verdict in the quiet conflict between two kinds of time. Pocket time with the chain, the search, and the consultation belonged to the world that had failed, while the wrist time with its strap, glance, and go, belonged to the one that survived.

Suddenly, what had been dismissed as a “silly ass fad” turned into a badge of survival. The wristwatch did not need a crown’s seal of approval—it already had one from every factory floor, school corridor, and tram conductor who wanted to be on time without fumbling with a chain.

And just like that, the world pretended it had always liked the idea.

From Fad to Factory Floor

Paris, 1918. The city wore rain like a favourite overcoat. Cobblestones soaked it up, cafés did their best umbrella impressions, and a Citroën barged through as if punctuation were optional. On the boulevard, two names—Omega and Longines—gleamed through the drizzle like they owned the alphabet.

Inside, pocket watches lounged on velvet like retired senators: polished, dignified, and mostly ignored. Up front, wristwatches sat on straps, trying hard not to look smug.

A clerk flipped a tray with the care of a man who has learned not to argue with habit. A veteran, cap tucked under his arm, tested a strap and lifted his wrist. In the trenches, that glance was a survival instinct; under the store’s gas lamp, it’s tinged with pleasure. The print was crisp, the minute track behaved, and the case edge responded to the light.

The salesman, not wanting to miss his line, tapped the glass: “Easy to read at a turn.” As if the trenches had been a focus group.

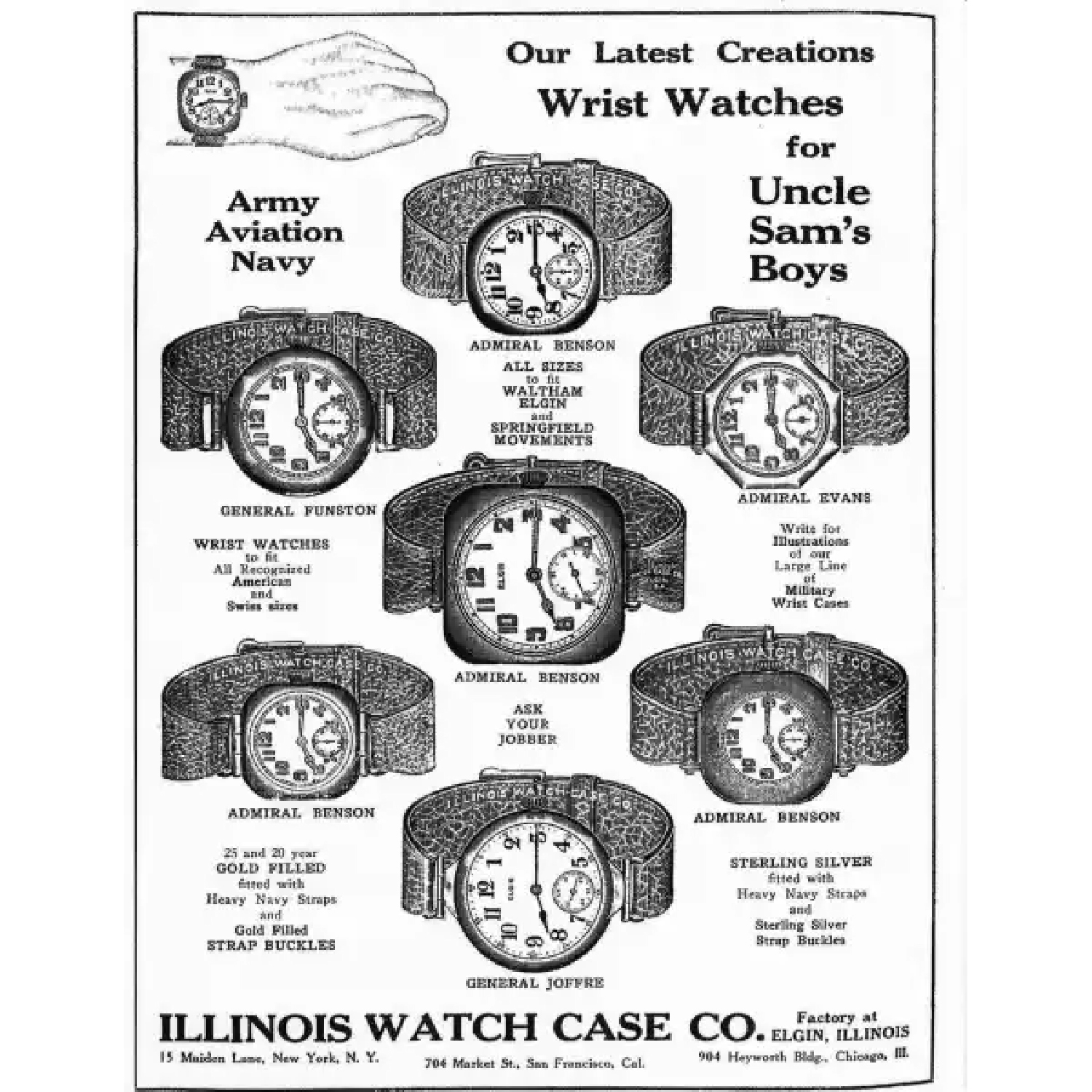

Catalogues on the counter finished the thought: pilots, motorists, men in shirtsleeves, different uniforms, all with the same gesture. Omega leaned on accuracy. Longines borrowed the airfield’s confidence. The wristwatch went to work on Monday. The pocket watch returned to weddings and toasts.

Efficiency, Cheekbones, and Other Selling Points

Post the war, elevators learned a new choreography. Doors parted, wrists rose, meetings began on time. The wristwatch soon became office shorthand, style without a word, status without the noise, and, most usefully, efficiency on tap. Wearing a watch meant you understood the new tempo. Punctuality was no longer a virtue, but competence.

Brands noticed and borrowed courage where the crowd had already looked. At airfields, Longines timed take-offs and landings, attaching its name to distance, weather and men who didn’t blink. In 1927, Rolex sent an Oyster across the English Channel on the wrist of Mercedes Gleitze and then put the proof on the front page.

The silver screen did the rest. Projector dust, a close-up, a strap on a cuff. When Rudolph Valentino wore his own Cartier in ‘The Son of the Sheikh’ (1926), the gesture stopped being a habit and became a wish. Suddenly, men weren’t just checking the hour, they were trying on a persona—modern, self-possessed, maybe even a touch dangerous. That tilt of the wrist sold more watches than a year of catalogues. The watch was no longer just practical or brave; it was handsome and desirable, and it knew it.

When Watches Went to Finishing School

Paris, 1925. At the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs, light spilt from the pavilions. Posters leaned under glass, their sunbursts and chevrons unbothered by weather. Tall capitals stood to attention. Cornices stepped like miniature ziggurats, doorways wore zigzags, chrome trims drew hard outlines in the wet, and taxi lamps dragged gold parentheses across the road. Everywhere you looked, geometry had a pulse, as if the city had been edited in straight lines.

Watches, never ones to miss a trend, joined in. The circle wasn’t banished, but rectangles had arrived with squared shoulders and a renewed purpose. The new language began with brancards that framed the dial, lugs that behaved correctly, and bezels that acknowledged the existence of screws. It was the time when numerals sharpened — serifed Romans, or stylised Arabics — while minute tracks learnt to mind their lanes. Dials picked up new tricks. Guilloches began to throw in a quiet sunburst, sector rings calmed the eye, and small seconds gave the hour room to breathe.

Cartier’s Tank stopped being a provocation and started looking inevitable. Across the channel and over the Atlantic, other houses added their steps to the dance. Vacheron Constantin tilted the dial in the American 1921 so drivers could check the time without also checking the nearest lamppost. Jaeger-LeCoultre, not to be left out, invented a watch case that flipped over in case someone tried polo indoors.

The trench had taught the wrist to glance. Art Deco taught it to look good while doing it. And in that marriage of function and vanity, the wristwatch finally became something worse than indispensable. It became fashionable.

Yet even as the wrist learned grace, it still had to learn to endure. Because elegance comes easily in fair weather, the real test begins when the sky turns grey.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

Paris 1901. A cigar-shaped balloon looped the Eiffel Tower while the city squinted upward. Ropes, gas, and a small engine combined to look like confidence, provided you didn’t stare too closely. Alberto Santos-Dumont circled the iron lattice and landed cleanly. Cleanly enough, at least. The stopwatch disagreed, ticking just over the limit.

The officials looked pained. Rules are rules after all. But Paris, being Paris, applauded as if being tardy were part of the charm. Eventually, the timekeepers began to feel they were the impolite ones.

A few days later, the Deutsch Prize found its winner, as it always meant to. That night, there was a table, a bottle, and two men who like problems. Santos-Dumont taps his waistcoat. “Up there, I fly with one hand and fish for time with the other. It’s foolish.” Louis Cartier listens, then sketches a square that won’t roll, a dial that reads at a glance, and a crown your fingers would find without thinking.

In 1904, the Cartier Santos arrived. It was among the first purpose-built wristwatches for men. A pilot’s gripe turned into a solution, and a fashion statement nobody had asked for but would eventually pretend they had always wanted.

An Invention Nobody Asked For

Cartier’s new square on a strap was less an invention, more a polite suggestion in a language no one wanted to learn. The world, still in love with its chains, gave him the sort of look usually reserved for avant-garde painters and people who ordered salads in steak houses.

It took a war to settle the argument — a very large, very loud one. By the time it ended, men stepped off trains thinner, quieter, and with no appetite for patting down their pockets in search of time. The paperwork of peace took longer than anyone had promised, and it had also delivered a final, brutal verdict in the quiet conflict between two kinds of time. Pocket time with the chain, the search, and the consultation belonged to the world that had failed, while the wrist time with its strap, glance, and go, belonged to the one that survived.

Suddenly, what had been dismissed as a “silly ass fad” turned into a badge of survival. The wristwatch did not need a crown’s seal of approval—it already had one from every factory floor, school corridor, and tram conductor who wanted to be on time without fumbling with a chain.

And just like that, the world pretended it had always liked the idea.

From Fad to Factory Floor

Paris, 1918. The city wore rain like a favourite overcoat. Cobblestones soaked it up, cafés did their best umbrella impressions, and a Citroën barged through as if punctuation were optional. On the boulevard, two names—Omega and Longines—gleamed through the drizzle like they owned the alphabet.

Inside, pocket watches lounged on velvet like retired senators: polished, dignified, and mostly ignored. Up front, wristwatches sat on straps, trying hard not to look smug.

A clerk flipped a tray with the care of a man who has learned not to argue with habit. A veteran, cap tucked under his arm, tested a strap and lifted his wrist. In the trenches, that glance was a survival instinct; under the store’s gas lamp, it’s tinged with pleasure. The print was crisp, the minute track behaved, and the case edge responded to the light.

The salesman, not wanting to miss his line, tapped the glass: “Easy to read at a turn.” As if the trenches had been a focus group.

Catalogues on the counter finished the thought: pilots, motorists, men in shirtsleeves, different uniforms, all with the same gesture. Omega leaned on accuracy. Longines borrowed the airfield’s confidence. The wristwatch went to work on Monday. The pocket watch returned to weddings and toasts.

Efficiency, Cheekbones, and Other Selling Points

Post the war, elevators learned a new choreography. Doors parted, wrists rose, meetings began on time. The wristwatch soon became office shorthand, style without a word, status without the noise, and, most usefully, efficiency on tap. Wearing a watch meant you understood the new tempo. Punctuality was no longer a virtue, but competence.

Brands noticed and borrowed courage where the crowd had already looked. At airfields, Longines timed take-offs and landings, attaching its name to distance, weather and men who didn’t blink. In 1927, Rolex sent an Oyster across the English Channel on the wrist of Mercedes Gleitze and then put the proof on the front page.

The silver screen did the rest. Projector dust, a close-up, a strap on a cuff. When Rudolph Valentino wore his own Cartier in ‘The Son of the Sheikh’ (1926), the gesture stopped being a habit and became a wish. Suddenly, men weren’t just checking the hour, they were trying on a persona—modern, self-possessed, maybe even a touch dangerous. That tilt of the wrist sold more watches than a year of catalogues. The watch was no longer just practical or brave; it was handsome and desirable, and it knew it.

When Watches Went to Finishing School

Paris, 1925. At the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs, light spilt from the pavilions. Posters leaned under glass, their sunbursts and chevrons unbothered by weather. Tall capitals stood to attention. Cornices stepped like miniature ziggurats, doorways wore zigzags, chrome trims drew hard outlines in the wet, and taxi lamps dragged gold parentheses across the road. Everywhere you looked, geometry had a pulse, as if the city had been edited in straight lines.

Watches, never ones to miss a trend, joined in. The circle wasn’t banished, but rectangles had arrived with squared shoulders and a renewed purpose. The new language began with brancards that framed the dial, lugs that behaved correctly, and bezels that acknowledged the existence of screws. It was the time when numerals sharpened — serifed Romans, or stylised Arabics — while minute tracks learnt to mind their lanes. Dials picked up new tricks. Guilloches began to throw in a quiet sunburst, sector rings calmed the eye, and small seconds gave the hour room to breathe.

Cartier’s Tank stopped being a provocation and started looking inevitable. Across the channel and over the Atlantic, other houses added their steps to the dance. Vacheron Constantin tilted the dial in the American 1921 so drivers could check the time without also checking the nearest lamppost. Jaeger-LeCoultre, not to be left out, invented a watch case that flipped over in case someone tried polo indoors.

The trench had taught the wrist to glance. Art Deco taught it to look good while doing it. And in that marriage of function and vanity, the wristwatch finally became something worse than indispensable. It became fashionable.

Yet even as the wrist learned grace, it still had to learn to endure. Because elegance comes easily in fair weather, the real test begins when the sky turns grey.