Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

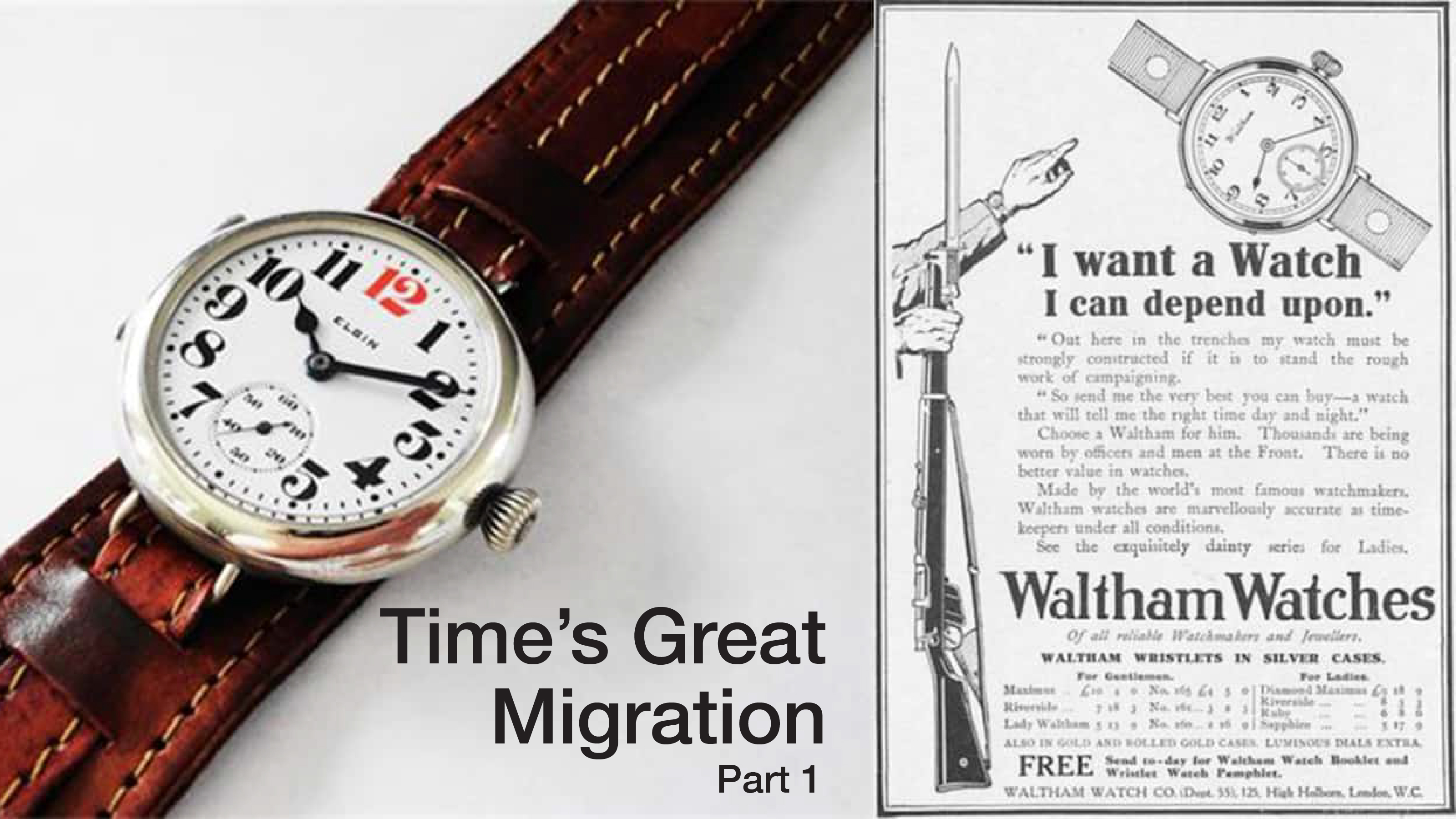

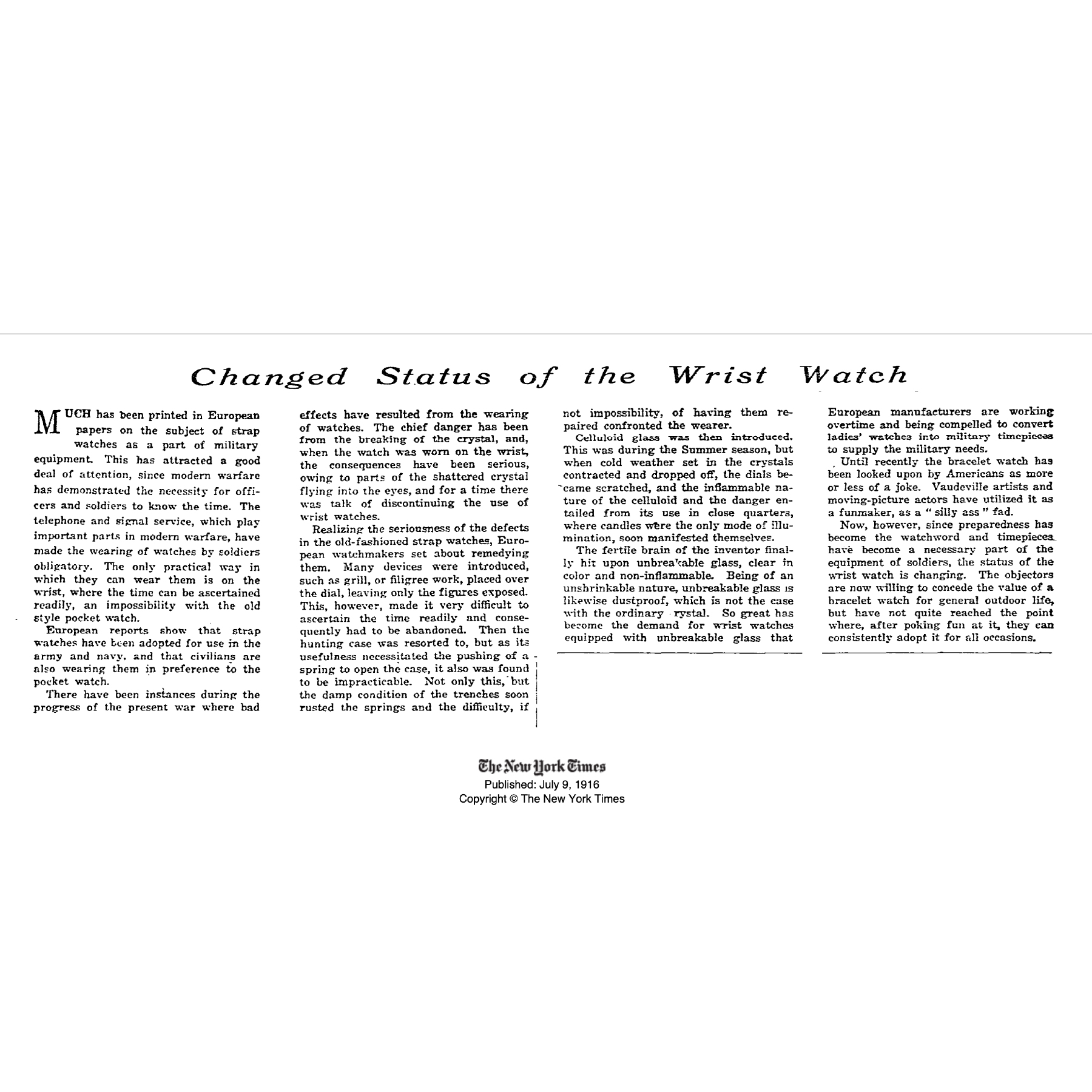

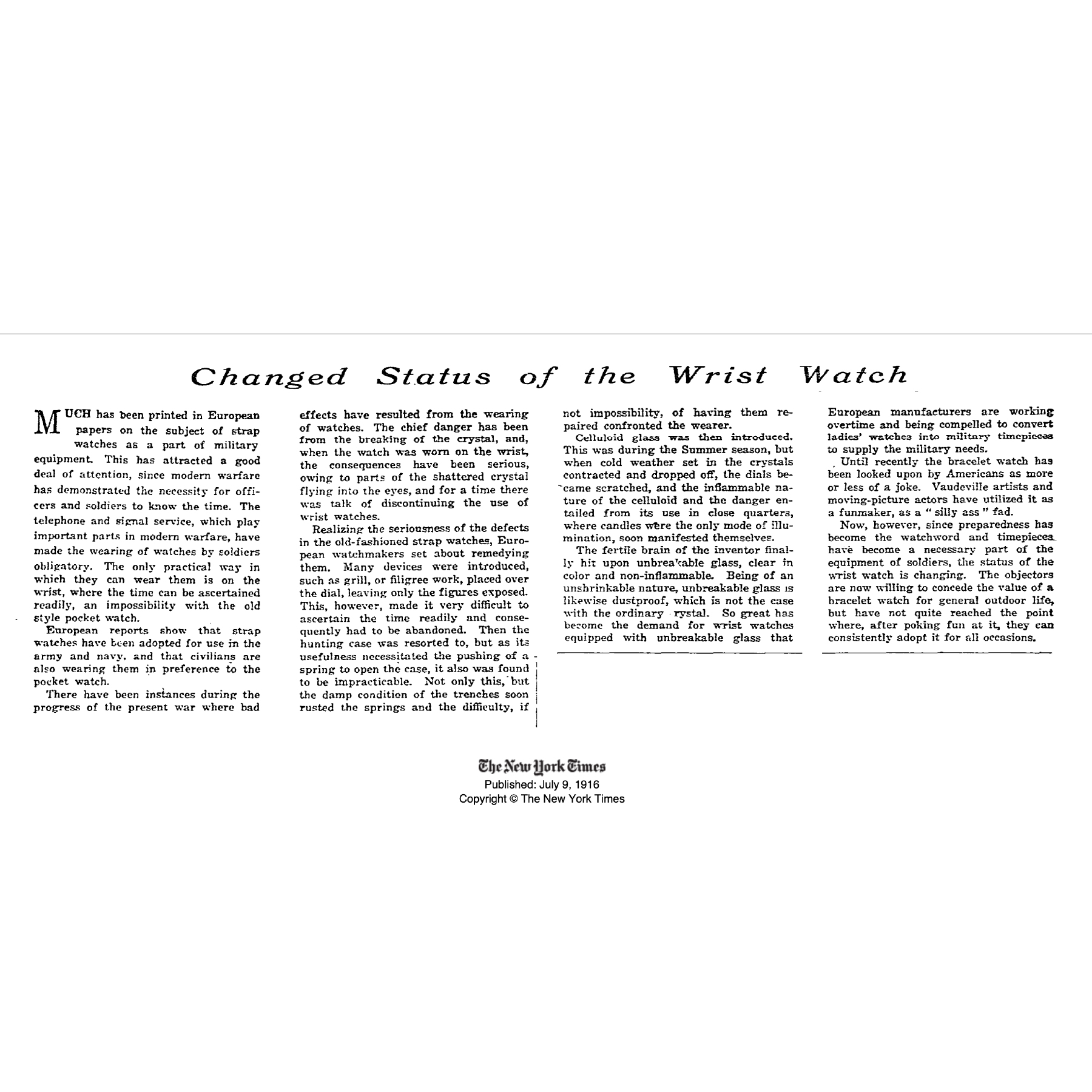

History rarely puts up neon signs. Most turns arrive like a shrug in the margins, a line you skim and only underline years later. On July 9, 1916, The New York Times ran one of those shrugs. From a Europe eating its rations and its nerves, men were reportedly wearing ‘bracelets with clocks on them.’ The tone was one of polite bafflement. The editorial equivalent of one eyebrow raised over tea. The wristlet, as it was called then, was supposed to be a delicate, sometimes bejewelled contrivance, worn almost exclusively by women who also wore titles. For men, it was unthinkable.

Fashion, they seemed to think. But what they were witnessing was a fundamental shift. Time was beginning its great migration from the pocket to the wrist.

The Breast Pocket

Before the bracelets, time lived in the pocket for a shade less than two and a half centuries. Checking it was a delicate theatre of punctuality and moral rectitude. It began not with a glance, but a search. Fingers reached for the pockets and found a familiar weight; a chain in precious metal lifted something trustworthy into the light. Your posture changed, too – shoulders squared, chin dipped – as if conferring at a lectern. In the palm, the watch had the heft of a decision. Porcelain under glass felt cool and smug in a world of friction and lint. The blued hands kept their temper like a well-brought-up child.

Your breath misted the crystal, and you polished it away with the same care you reserve for spectacles and stubborn thoughts, and then the sound, the hunter case giving up its secret with that clean, satisfying click. This wasn’t data, it was counsel. A quiet word with an old friend about order and respect, then a courteous goodbye as you slipped it back, the gesture saying as much as the hour.

At night, you wound it, steady turns counted by habit, so that tomorrow would arrive on schedule. Punctuality, once considered a branch of good manners, lived here.

Pocket time suited a roomed life. Desks with blotters, trains with timetables, parlours with carpets that would forgive dropped chains. Tailors even cut little watch pockets as if civility were a garment. If you forgot to consult the hour, that was your prerogative. Time waited in the wings, patient as a butler.

Then, the appointment was overruled by war.

The Trenches

A candle burns low in a mess tin, making a small lake of light on four faces. Mud holds the walls up. Breath ghosts in the cold. “Time?” the lieutenant says. Not loudly, just enough for the trench to hear. Leather straps creak as sleeves hitch back. Numerals bloom a dull, sickly green. A private wipes grit from his crystal with the side of a thumb; another taps a crown to be sure it’s seated. Someone kisses a locket, gently. Down the line, a whistle cord is already between someone’s teeth. Zero hour is a rumour morphing into a fact.

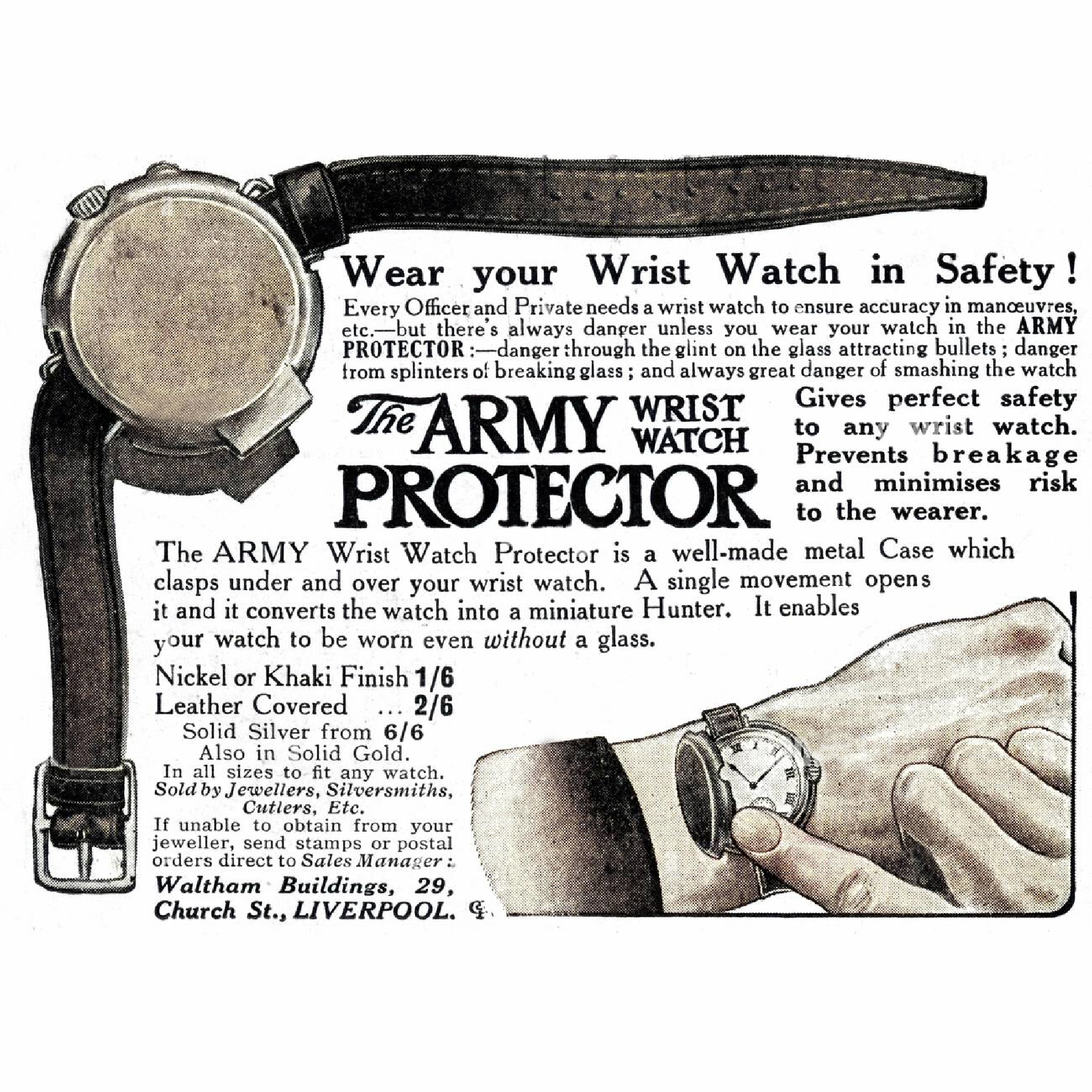

This was a war of timetables. Time had shed its politeness to become a cruel metronome, setting the pace for synchronised attacks where a single fumbled second could orphan a family. The quiet ceremony of the pocket watch was now a flaw you could die of. Try consulting a delicate, fob-chained friend while crawling on your belly, the air thick with shrapnel and prayer. Try unveiling its secrets with frozen, mud-caked fingers. Fashion took one look at the mud and sat this one out.

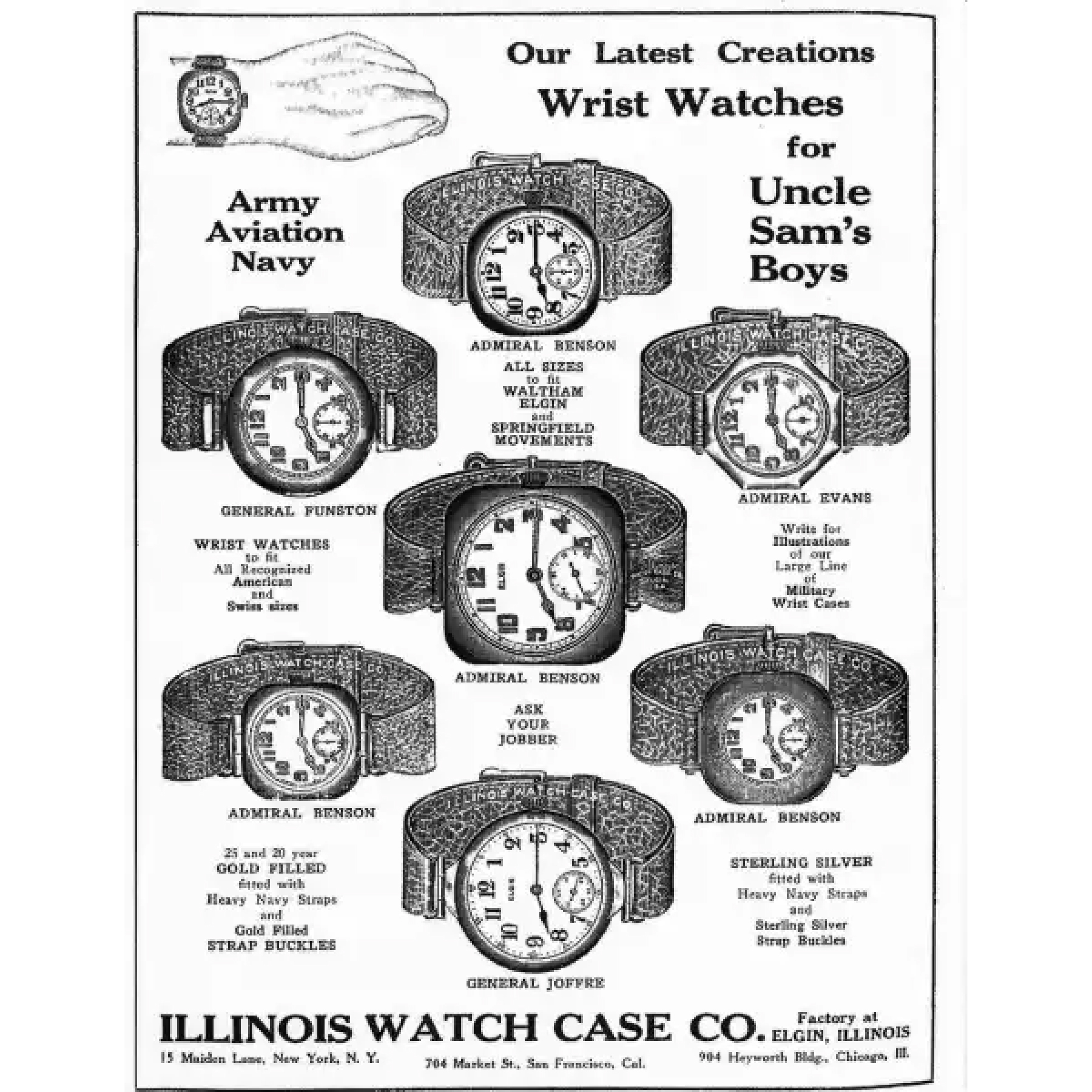

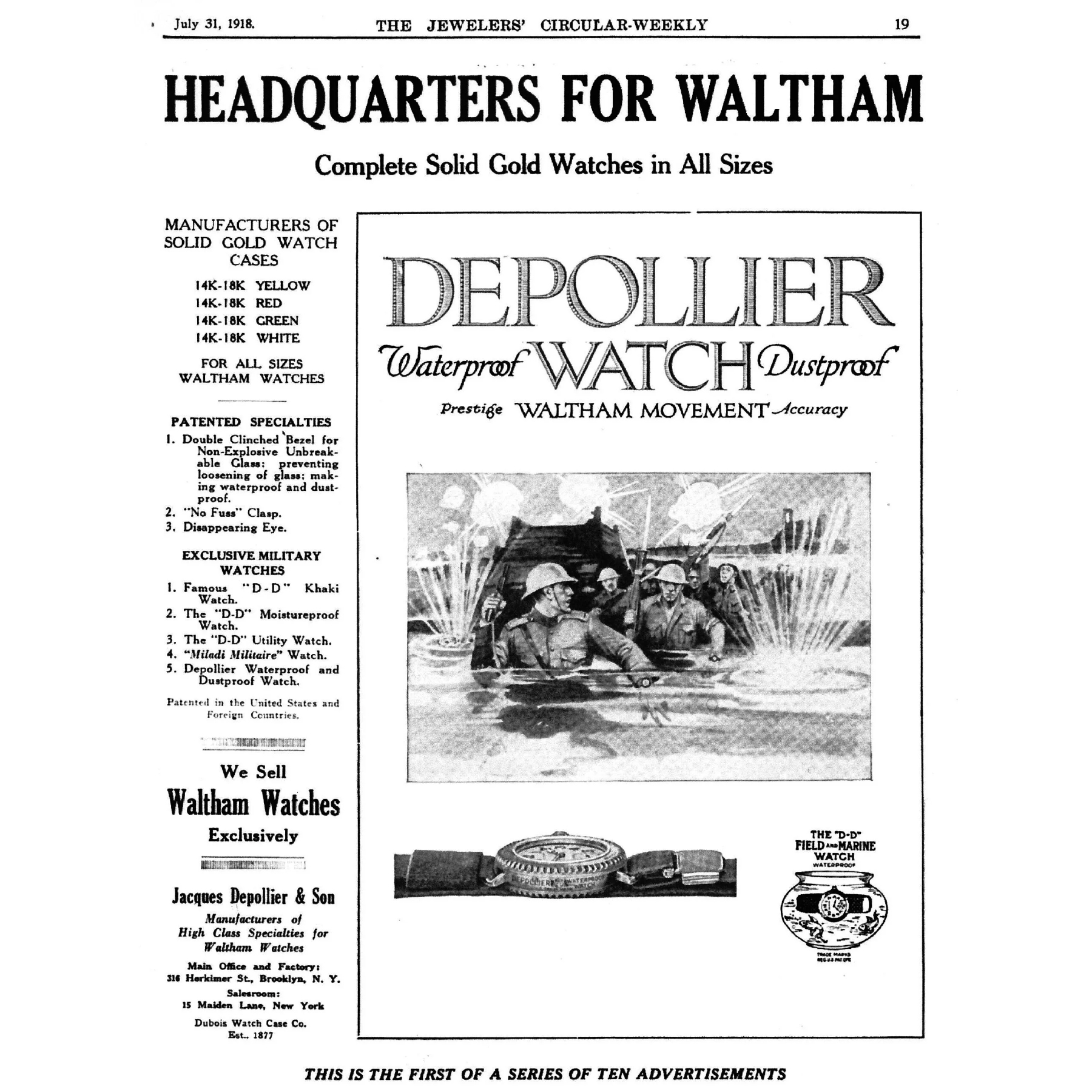

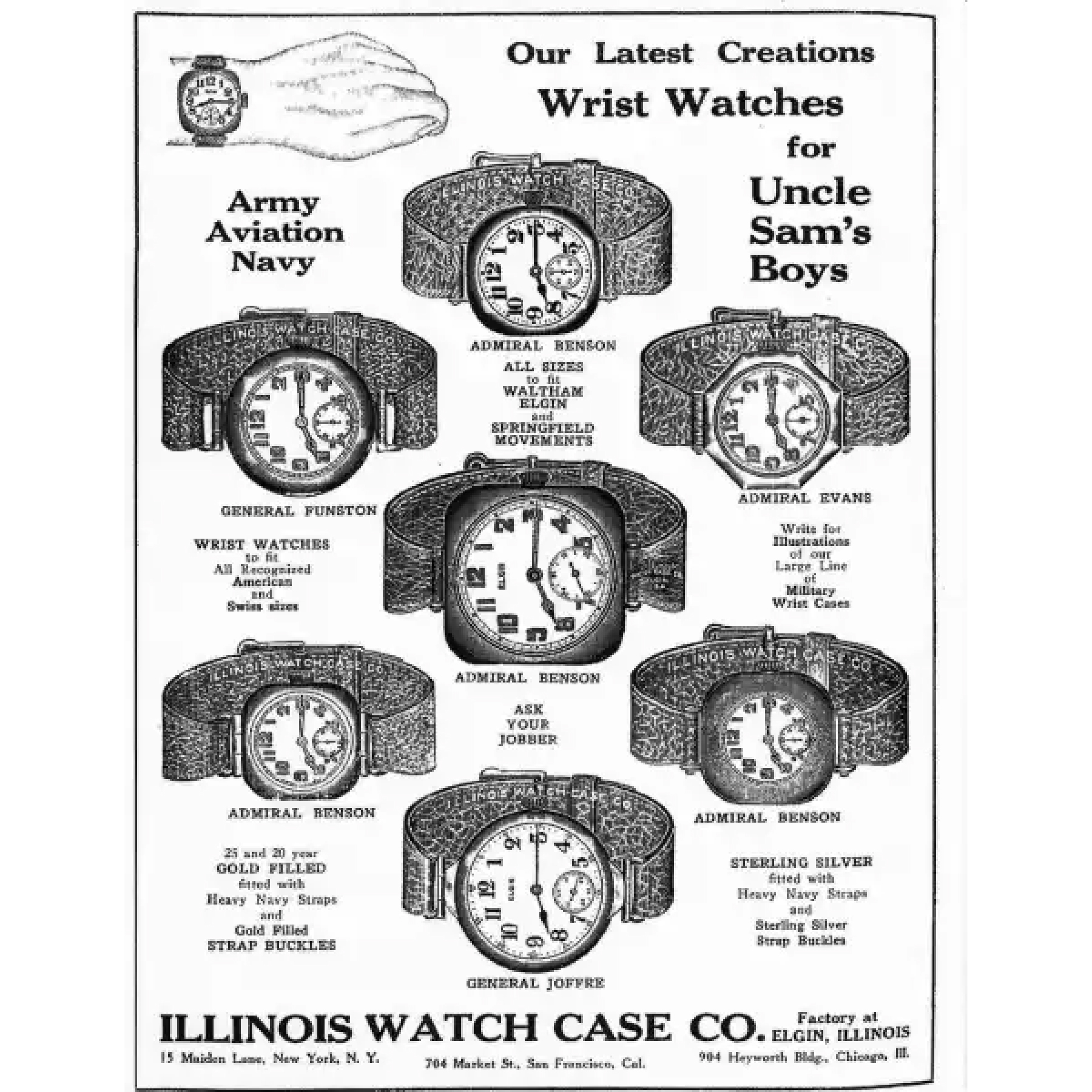

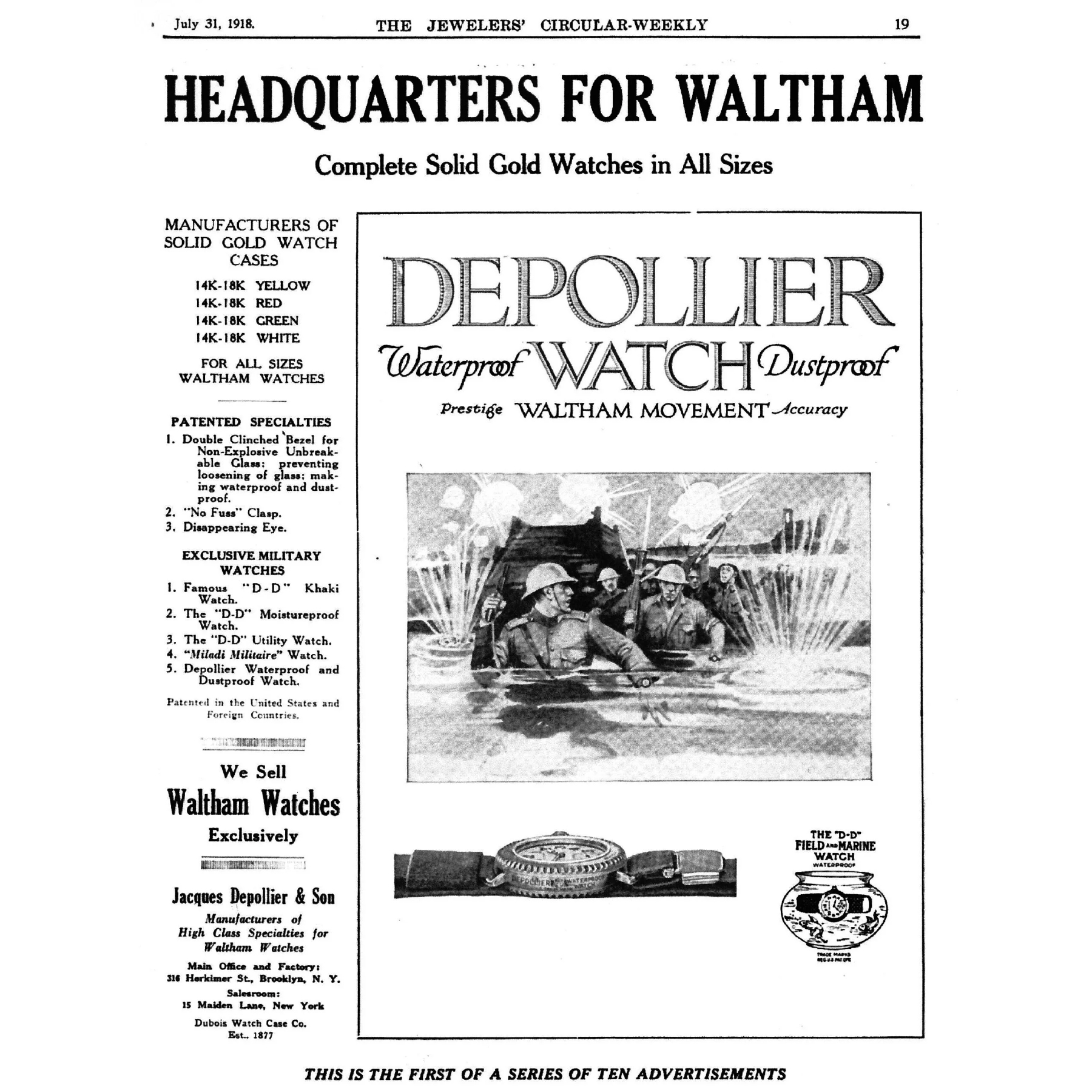

What was needed were numbers that could shout in the dark, hands that could be read between shell bursts, a strap that bit and stayed. This is where the wristwatch was born. Not in a pristine Swiss workshop as the next big thing, but as a rugged, desperate solution. Wire lugs were soldered onto cases; strips of tired leather and canvas were threaded through until they remembered the wrist. Time was conscripted, promoted, and rarely demobilised. The hours now sweated through wool, and the minutes smelled faintly of soup, oil, and fear.

Time stopped being a guest and became the warden. Its face drilled into visibility at all hours. Whistles, flares, and the sweep hand had to agree before men climbed out. Artillery tables and narrow dials learned to nod at each other. If you could see it, you could live.

Between stand-to at dawn and the ration party at dusk, time refused to be summoned and insisted on being seen. Sleeves loosened, habits hardened, and a glance became a technique. The migration of time was no longer a theory. It was survival.

The Streets

When the soldiers returned, they carried the war in their silence, and the future on their wrists. The bracelet with a clock on it, once suitable for a chuckle at the club, was now a badge. Next to it, the old guard, the pocket watch looked winded, like a gentleman who’d mistaken a parade for a ballroom.

The slow, private ritual began to feel less like distinction and more like fuss. It now belonged to a man who had never needed to check the time with his hands shaking. It was the watch of the banker, the politician, and the factory owners. Men who commanded hours from behind a mahogany table, while others spent theirs in mud and blood. Its gentle ticking was the soundtrack of inherited certainties. Those certainties had washed away.

Life itself was speeding. A hand on the wheel of a Ford and the other around your sweetheart. A tram bell. A conductor’s punch. A telephone insisting from the hallway. The Charleston asked for a beat you could catch without breaking stride, and you couldn’t fish for a pocket watch in that tempo.

The wristwatch became the native tongue of this new era—read on bicycles, in shop queues, on scaffolds, at kitchen sinks. It democratised the glance. A mother timed the milkman and the fever. A boy traced his father’s new strap and learned, wordlessly, that some habits come home and stay. Office girls borrowed their brothers’ trench watches and forgot to return them. The technology had changed its address, and everything else had to follow.

With every (un)ceremonious look, the migration settled into culture. The watch moved from counsel to command and finally to companion. No longer summoned in a study. No longer deciding between a charge and a slaughter. Simply visible, available, quietly insistent.

The legacy of those trenches is that small patch of skin that now feels naked without a watch. We still wear the echo of that century-old order : the hunter case’s click traded for the trench whistle’s scream, both softened now into the everyday mercy of a clasp’s bite. But before the world could soften those echoes into civility, the wristwatch had to give in to vanity and learn to dance.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

History rarely puts up neon signs. Most turns arrive like a shrug in the margins, a line you skim and only underline years later. On July 9, 1916, The New York Times ran one of those shrugs. From a Europe eating its rations and its nerves, men were reportedly wearing ‘bracelets with clocks on them.’ The tone was one of polite bafflement. The editorial equivalent of one eyebrow raised over tea. The wristlet, as it was called then, was supposed to be a delicate, sometimes bejewelled contrivance, worn almost exclusively by women who also wore titles. For men, it was unthinkable.

Fashion, they seemed to think. But what they were witnessing was a fundamental shift. Time was beginning its great migration from the pocket to the wrist.

The Breast Pocket

Before the bracelets, time lived in the pocket for a shade less than two and a half centuries. Checking it was a delicate theatre of punctuality and moral rectitude. It began not with a glance, but a search. Fingers reached for the pockets and found a familiar weight; a chain in precious metal lifted something trustworthy into the light. Your posture changed, too – shoulders squared, chin dipped – as if conferring at a lectern. In the palm, the watch had the heft of a decision. Porcelain under glass felt cool and smug in a world of friction and lint. The blued hands kept their temper like a well-brought-up child.

Your breath misted the crystal, and you polished it away with the same care you reserve for spectacles and stubborn thoughts, and then the sound, the hunter case giving up its secret with that clean, satisfying click. This wasn’t data, it was counsel. A quiet word with an old friend about order and respect, then a courteous goodbye as you slipped it back, the gesture saying as much as the hour.

At night, you wound it, steady turns counted by habit, so that tomorrow would arrive on schedule. Punctuality, once considered a branch of good manners, lived here.

Pocket time suited a roomed life. Desks with blotters, trains with timetables, parlours with carpets that would forgive dropped chains. Tailors even cut little watch pockets as if civility were a garment. If you forgot to consult the hour, that was your prerogative. Time waited in the wings, patient as a butler.

Then, the appointment was overruled by war.

The Trenches

A candle burns low in a mess tin, making a small lake of light on four faces. Mud holds the walls up. Breath ghosts in the cold. “Time?” the lieutenant says. Not loudly, just enough for the trench to hear. Leather straps creak as sleeves hitch back. Numerals bloom a dull, sickly green. A private wipes grit from his crystal with the side of a thumb; another taps a crown to be sure it’s seated. Someone kisses a locket, gently. Down the line, a whistle cord is already between someone’s teeth. Zero hour is a rumour morphing into a fact.

This was a war of timetables. Time had shed its politeness to become a cruel metronome, setting the pace for synchronised attacks where a single fumbled second could orphan a family. The quiet ceremony of the pocket watch was now a flaw you could die of. Try consulting a delicate, fob-chained friend while crawling on your belly, the air thick with shrapnel and prayer. Try unveiling its secrets with frozen, mud-caked fingers. Fashion took one look at the mud and sat this one out.

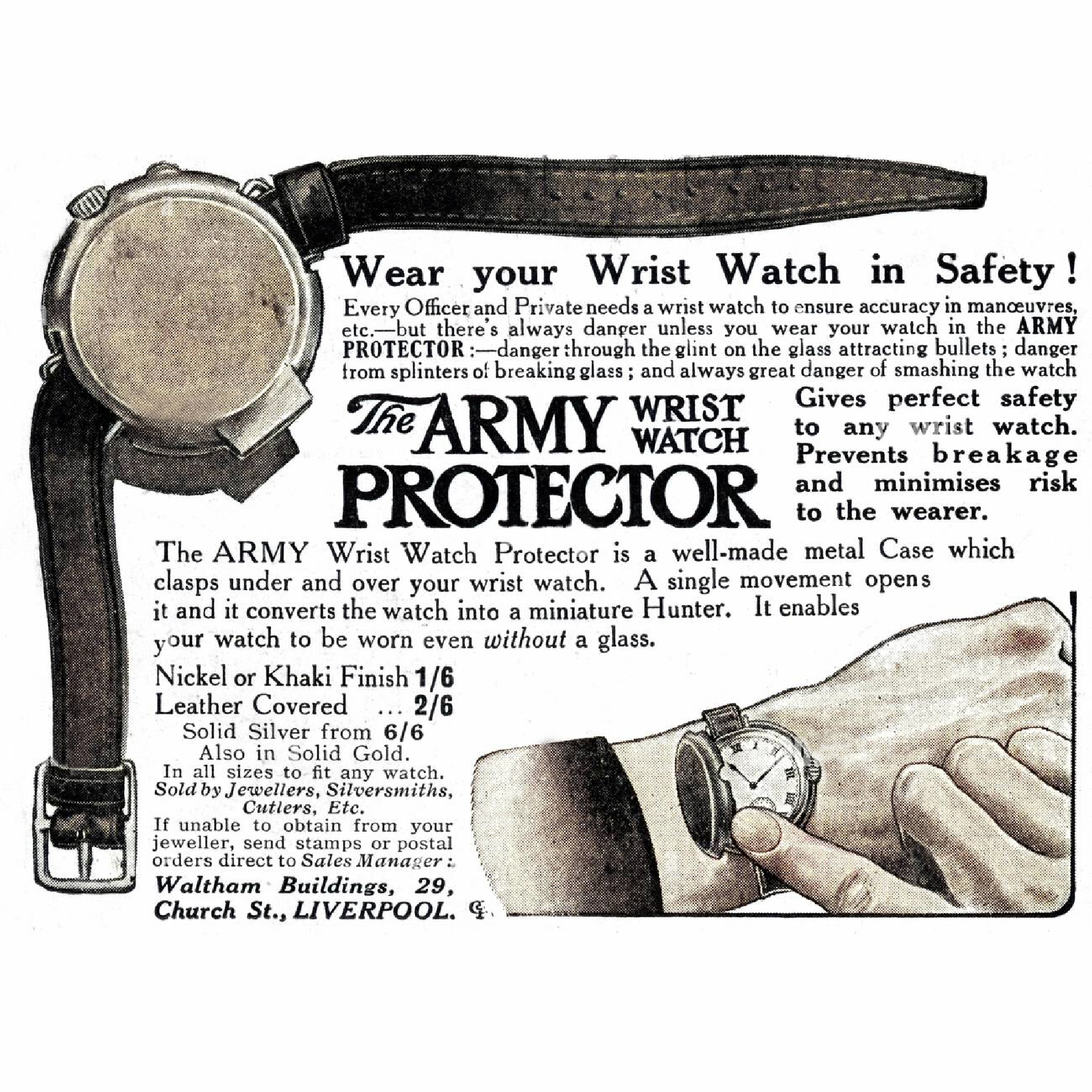

What was needed were numbers that could shout in the dark, hands that could be read between shell bursts, a strap that bit and stayed. This is where the wristwatch was born. Not in a pristine Swiss workshop as the next big thing, but as a rugged, desperate solution. Wire lugs were soldered onto cases; strips of tired leather and canvas were threaded through until they remembered the wrist. Time was conscripted, promoted, and rarely demobilised. The hours now sweated through wool, and the minutes smelled faintly of soup, oil, and fear.

Time stopped being a guest and became the warden. Its face drilled into visibility at all hours. Whistles, flares, and the sweep hand had to agree before men climbed out. Artillery tables and narrow dials learned to nod at each other. If you could see it, you could live.

Between stand-to at dawn and the ration party at dusk, time refused to be summoned and insisted on being seen. Sleeves loosened, habits hardened, and a glance became a technique. The migration of time was no longer a theory. It was survival.

The Streets

When the soldiers returned, they carried the war in their silence, and the future on their wrists. The bracelet with a clock on it, once suitable for a chuckle at the club, was now a badge. Next to it, the old guard, the pocket watch looked winded, like a gentleman who’d mistaken a parade for a ballroom.

The slow, private ritual began to feel less like distinction and more like fuss. It now belonged to a man who had never needed to check the time with his hands shaking. It was the watch of the banker, the politician, and the factory owners. Men who commanded hours from behind a mahogany table, while others spent theirs in mud and blood. Its gentle ticking was the soundtrack of inherited certainties. Those certainties had washed away.

Life itself was speeding. A hand on the wheel of a Ford and the other around your sweetheart. A tram bell. A conductor’s punch. A telephone insisting from the hallway. The Charleston asked for a beat you could catch without breaking stride, and you couldn’t fish for a pocket watch in that tempo.

The wristwatch became the native tongue of this new era—read on bicycles, in shop queues, on scaffolds, at kitchen sinks. It democratised the glance. A mother timed the milkman and the fever. A boy traced his father’s new strap and learned, wordlessly, that some habits come home and stay. Office girls borrowed their brothers’ trench watches and forgot to return them. The technology had changed its address, and everything else had to follow.

With every (un)ceremonious look, the migration settled into culture. The watch moved from counsel to command and finally to companion. No longer summoned in a study. No longer deciding between a charge and a slaughter. Simply visible, available, quietly insistent.

The legacy of those trenches is that small patch of skin that now feels naked without a watch. We still wear the echo of that century-old order : the hunter case’s click traded for the trench whistle’s scream, both softened now into the everyday mercy of a clasp’s bite. But before the world could soften those echoes into civility, the wristwatch had to give in to vanity and learn to dance.