Join CHRONOHOLIC today!

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

All the watch news, reviews, videos you want, brought to you from fellow collectors

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

2016 was a loud year, resplendent in its distractions.

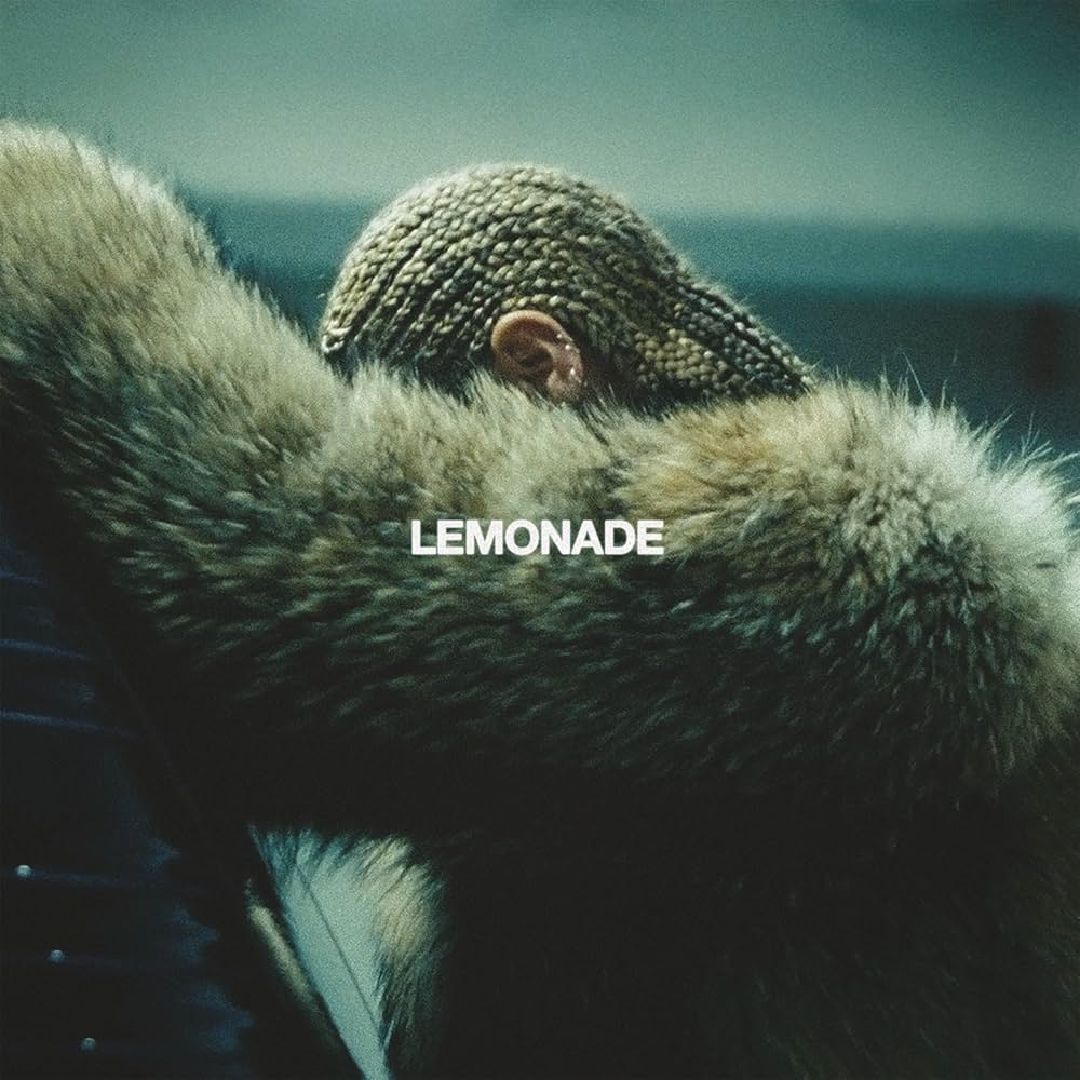

It was the year the world, in a collective fit of new nostalgia, went outside to hunt for digital monsters on its phones. Pokémon Go had convinced an entire generation to hunt for ghosts on their screens rather than the ones in their bones. On our playlists, Beyoncé had served Lemonade, an album so culturally potent it felt less like a record and more like a global weather event. On our televisions, Stranger Things began its expert repackaging of the 80s, a decade we were all suddenly, and safely, ready to miss.

The noise was bright, digital, and deafening.

And so, almost no one heard a door being quietly locked in India. In January of that year, the machines at HMT’s watch division fell silent for good. It wasn’t a scandal. It didn’t trend. It was an obituary of a time written in a language that the new, loud world no longer knew how to read.

The Ghost of Absence

For me, the news didn't conjure images of silent factories or forgotten ledgers. It brought back a ghost. The small, gentle ghost of an HMT, perhaps a Janata, that used to sit on my father’s nightstand.

It wasn’t the kind of watch that ever started a conversation. There was nothing glamorous about it, no flourish in its hands, no arrogance in its strap. It was made for men who didn’t chase time so much as accompany it. Men who wound their watches every night not to master the hours, but to honour their passing.

Every evening, before turning off the light, my father would take it off and place it beside his bed, a small ritual that felt less like a habit and more like trust. The Janata was an unassuming companion, the sort of watch that believed in its own purpose quietly.

When I heard that HMT had shut down, I thought of that watch. Of the faint ring it left on my father’s wrist. Of how its patient ticking held an entire generation’s faith in the slow, deliberate making of things.

The Sound of Making

A new country is, perhaps, the most audacious of all ideas. In the 1950s, India was precisely that. A sprawling, ancient belief suddenly asked to reinvent itself. It decided to run on five-year plans, and the ambitious sound of concrete being poured. This was a nation that had to believe in a schedule.

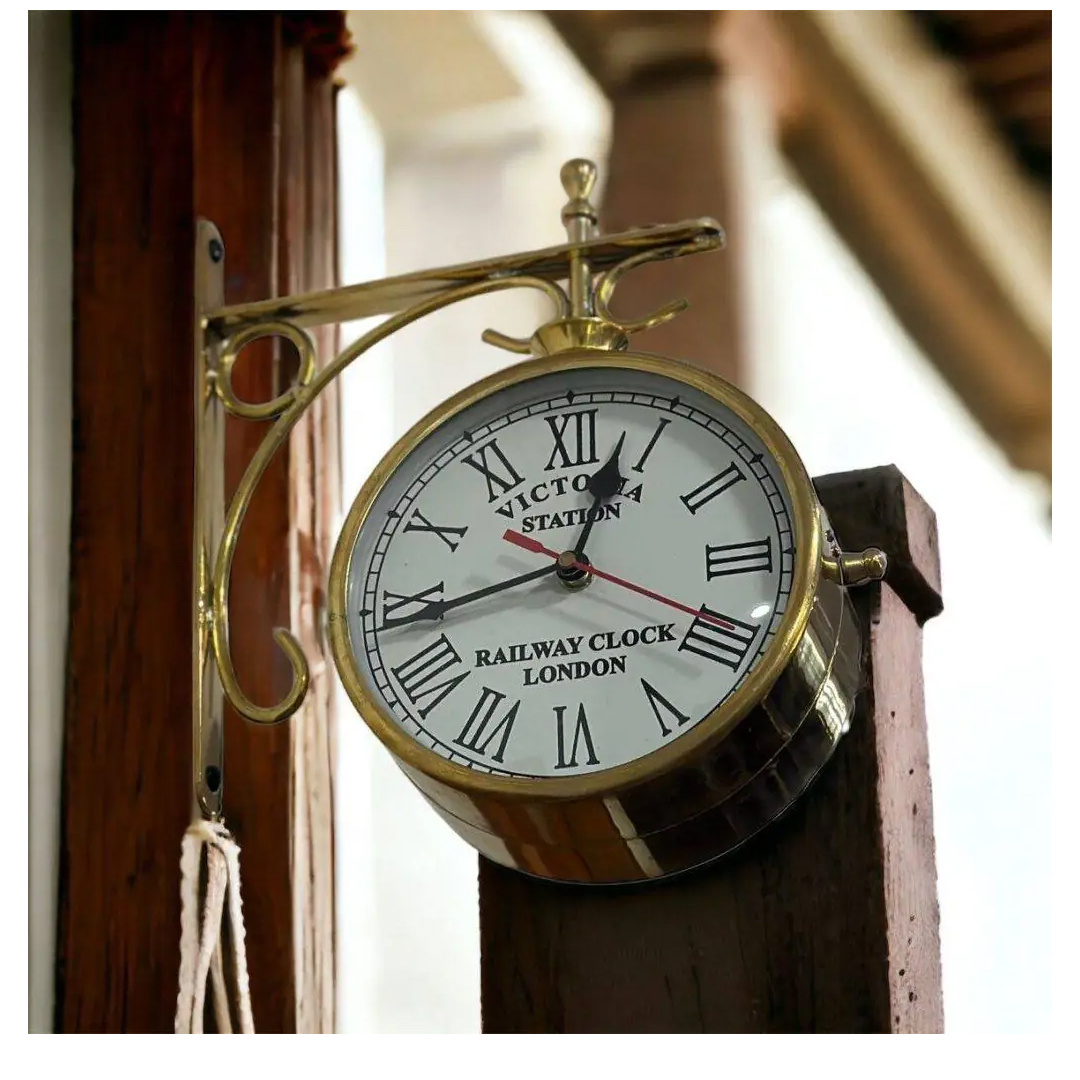

But what clock does a new nation tick by? Before India began to write its tryst with destiny, hours were measured in the heavy chimes of British-made clocks in railway offices, or in the inherited weight of Swiss-made timepieces. Both reminders of an age that we had fought hard to put behind us. A new India needed its own pulse. It needed a machine for the wrist of the engineer, the clerk, and the worker.

And so, it looked at Hindustan Machine Tools, the maker of lathes, grinders and milling machines. HMT, since 1953, had been making unglamorous machines that sang a metallic symphony of rotation, grit and intent. Each turn of a handle, each cut of steel, was a declaration that India could make its own tools and, by extension, its own future.

The country, however, wanted something smaller, more intricate and somehow grander. A wristwatch. It was an unlikely brief. To ask a company that built machines for factories to build a machine for the wrist. Then again, post-independence India had made a quiet art of making do, of chasing the improbable with tools fashioned from necessity.

HMT first knocked on Seiko’s door, but Japan’s most punctual watchmaker politely declined. The proposal then crossed Osaka to a neighbour, Citizen, who agreed to collaborate. The partnership turned out to be as philosophical as it was technical. Japan supplied precision and method. India provided the ingenuity to make it affordable for the everyday man.

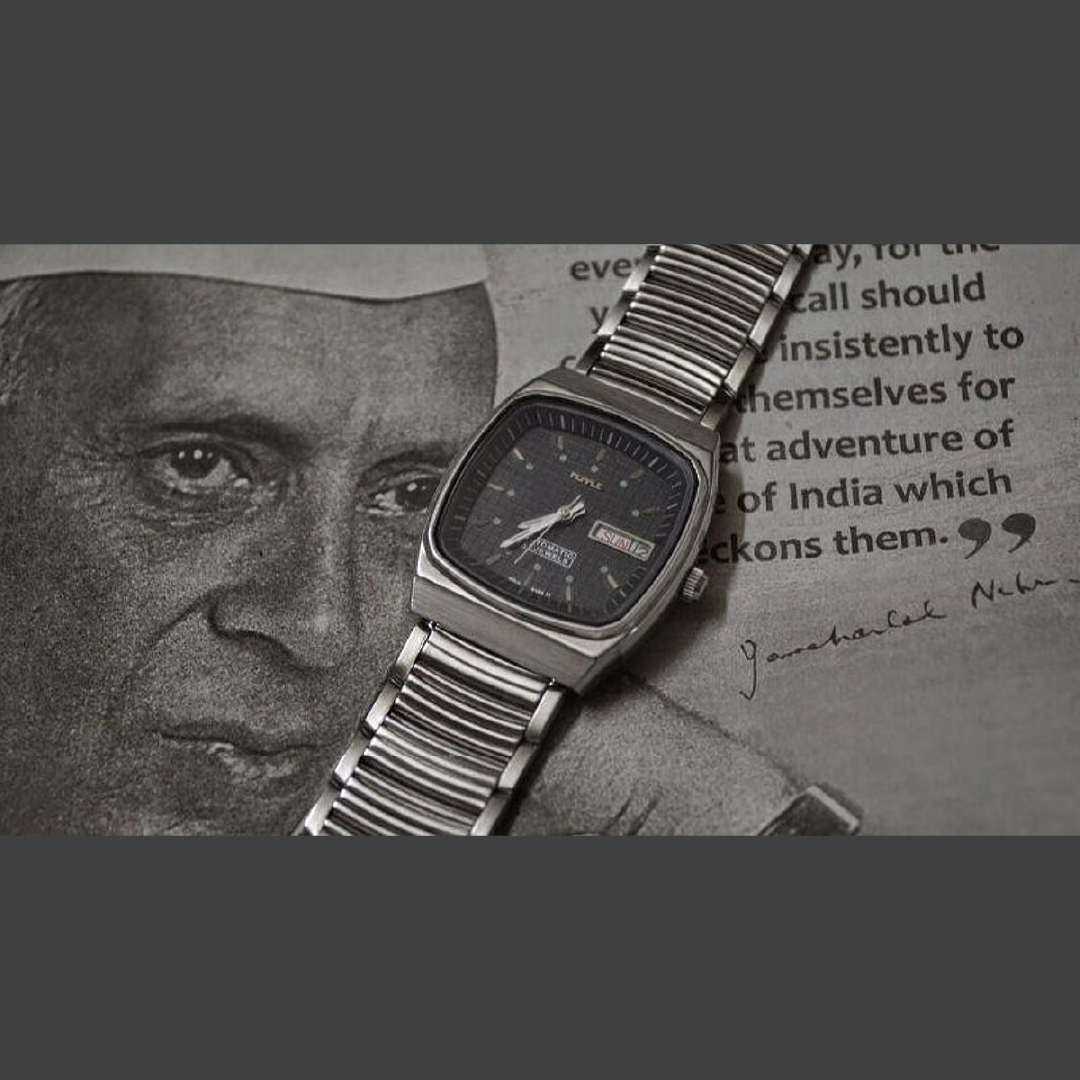

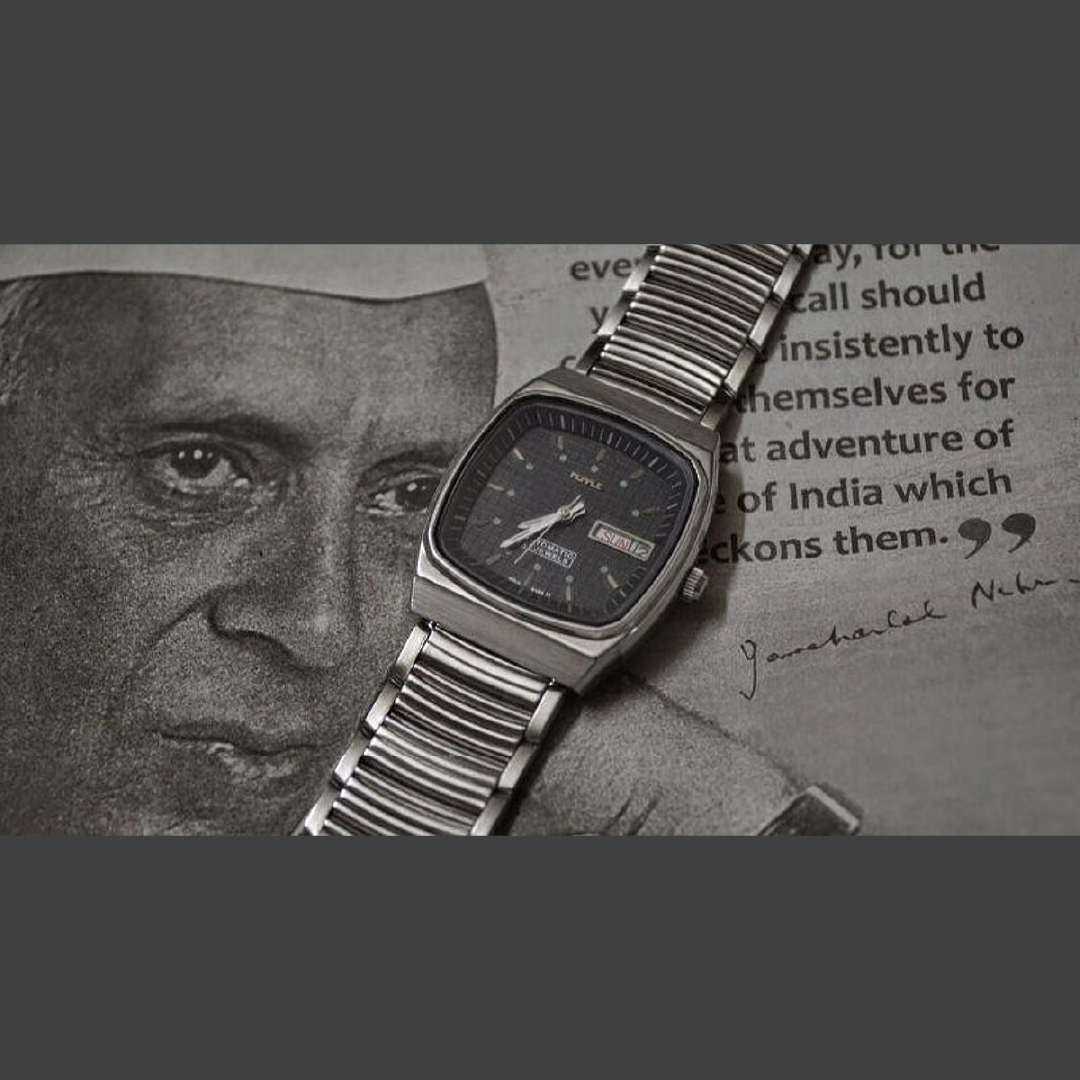

The first HMT watch was assembled in 1962 at the new Bangalore plant. When the inaugural piece was presented to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, he did not treat it as a ceremonial token. He slipped it on. The model would later be called the Janata, meaning ‘the people,’ a fitting name for a watch that would come to define the wrist of a generation.

It was modest, mechanical and humble in its geometry. The dial was clean and unadorned, its numerals as practical as its purpose. It was not designed to dazzle but to endure. Over the following decades, millions like my father would wear it each day, then leave it on their nightstands for their children to gaze at and dream of owning one someday.

It was the time of small dreams. It was the time of HMT.

The Uniform of a Generation

The first watches from HMT were mostly assembled from imported parts, their movements licensed from Citizen, their gears whispering in a borrowed language. In less than a decade, though, the assembly line had turned into an ecosystem of self-reliance.

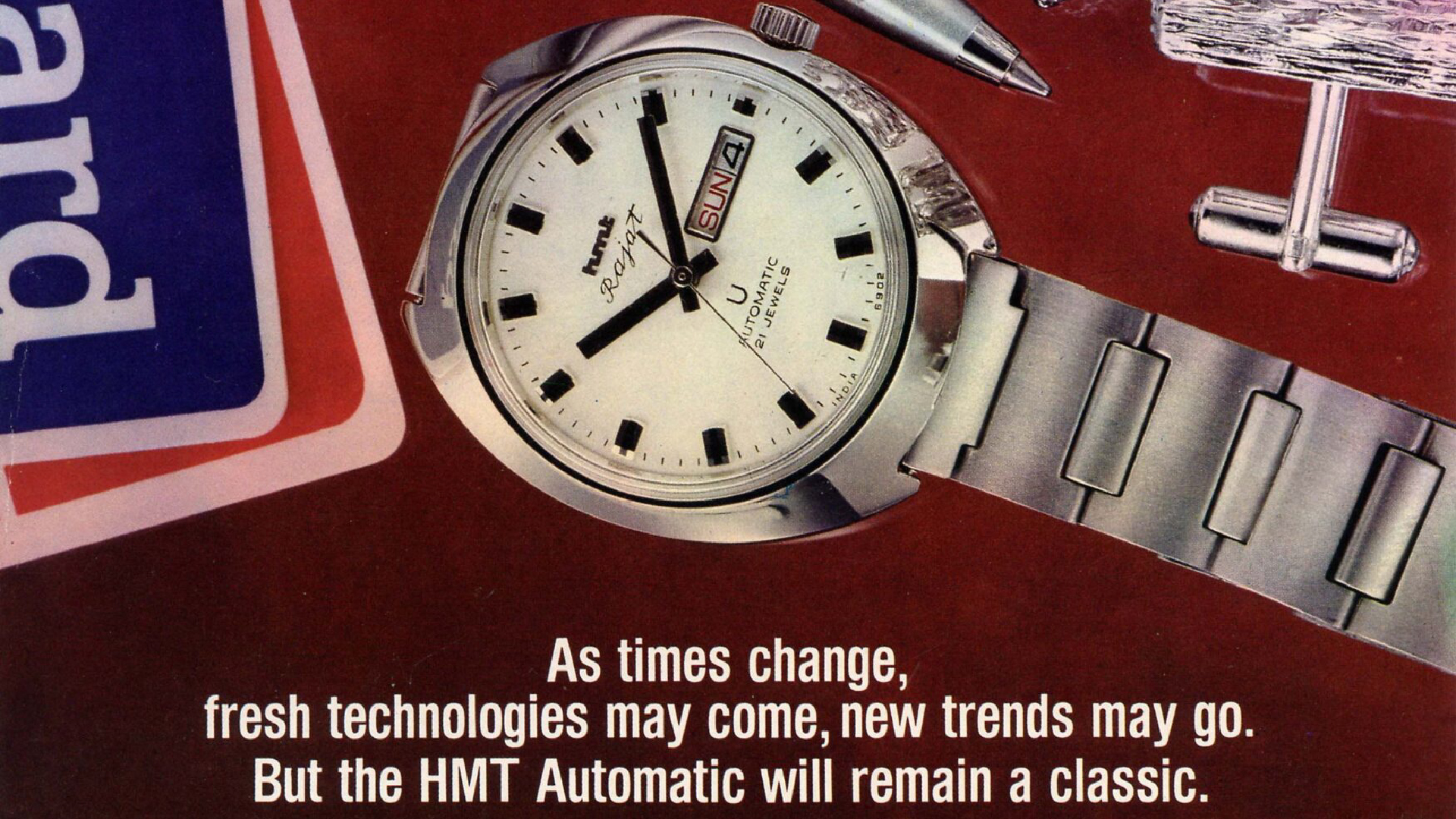

As India grew, so did its timekeeper. The Janata soon found company. The Pilot arrived as a small, black-dialled watch with a sky-adjacent myth. It was the watch for the man who saw himself as a quiet hero, even if his only fighter jet was the crowded 8:05 local. Then came the Sona, a slim, gold-plated wafer that gleamed from beneath crisp shirt cuffs. This was HMT in its formal attire, the watch that emerged from its velvet box for weddings and interviews.

There was the Jawan, Kanchan, Rajat, Sanjay and Kohinoor, each name a small performance of aspiration. In the India of yore, these watches were not bought, but earned. They became the standard-issue reward for an Indian life lived well. An HMT marked each milestone. You received one when you graduated from college, a ticket to the world of adult responsibility. You were gifted one at your wedding, a quiet wish for prosperous times. And after thirty years of loyal service, you were presented with a gold-plated Kanchan or Rajat, a heavy, automatic thank-you for a lifetime of hours.

By the 1980s, to look around a government office, a university classroom, or a train compartment was to see a sea of HMTs. The brand had become the nation’s unofficial uniform. Waiting lists sometimes stretched for months. There were even stories of weddings postponed until a ‘Sanjay’ could be secured for Sanjay.

HMT was no longer just a watchmaker. It had become a quiet institution, churning out two million watches a year across its various factories. They were the shared pulse that bound the country’s working hands together. Each tick was a small, collective affirmation that India was, at last, keeping its own time.

The Missed Beat

By the 1990s, though, the rhythm had begun to change. Liberalisation arrived like a new calendar, shiny, unpredictable and printed elsewhere. The old certainties of state planning gave way to the chaos of choice. And HMT, honest in its steel and stubborn in its sincerity, found itself out of sync. Its designs looked tired, its technology slower than the world it once helped to measure.

In a country that had long worn its watches as proof of arrival, HMT’s humility became its undoing. The same quiet dignity that once made it universal now made it invisible. It was a watch built for a nation of engineers and clerks, not for one discovering consumers and careers.

India had moved on to watches that no longer needed winding, and those that sparkled under showroom lights. HMT ticked on resolutely for a few more decades, but its seconds no longer belonged to the future.

%20(1).jpeg)

%20(1).jpeg)

2016 was a loud year, resplendent in its distractions.

It was the year the world, in a collective fit of new nostalgia, went outside to hunt for digital monsters on its phones. Pokémon Go had convinced an entire generation to hunt for ghosts on their screens rather than the ones in their bones. On our playlists, Beyoncé had served Lemonade, an album so culturally potent it felt less like a record and more like a global weather event. On our televisions, Stranger Things began its expert repackaging of the 80s, a decade we were all suddenly, and safely, ready to miss.

The noise was bright, digital, and deafening.

And so, almost no one heard a door being quietly locked in India. In January of that year, the machines at HMT’s watch division fell silent for good. It wasn’t a scandal. It didn’t trend. It was an obituary of a time written in a language that the new, loud world no longer knew how to read.

The Ghost of Absence

For me, the news didn't conjure images of silent factories or forgotten ledgers. It brought back a ghost. The small, gentle ghost of an HMT, perhaps a Janata, that used to sit on my father’s nightstand.

It wasn’t the kind of watch that ever started a conversation. There was nothing glamorous about it, no flourish in its hands, no arrogance in its strap. It was made for men who didn’t chase time so much as accompany it. Men who wound their watches every night not to master the hours, but to honour their passing.

Every evening, before turning off the light, my father would take it off and place it beside his bed, a small ritual that felt less like a habit and more like trust. The Janata was an unassuming companion, the sort of watch that believed in its own purpose quietly.

When I heard that HMT had shut down, I thought of that watch. Of the faint ring it left on my father’s wrist. Of how its patient ticking held an entire generation’s faith in the slow, deliberate making of things.

The Sound of Making

A new country is, perhaps, the most audacious of all ideas. In the 1950s, India was precisely that. A sprawling, ancient belief suddenly asked to reinvent itself. It decided to run on five-year plans, and the ambitious sound of concrete being poured. This was a nation that had to believe in a schedule.

But what clock does a new nation tick by? Before India began to write its tryst with destiny, hours were measured in the heavy chimes of British-made clocks in railway offices, or in the inherited weight of Swiss-made timepieces. Both reminders of an age that we had fought hard to put behind us. A new India needed its own pulse. It needed a machine for the wrist of the engineer, the clerk, and the worker.

And so, it looked at Hindustan Machine Tools, the maker of lathes, grinders and milling machines. HMT, since 1953, had been making unglamorous machines that sang a metallic symphony of rotation, grit and intent. Each turn of a handle, each cut of steel, was a declaration that India could make its own tools and, by extension, its own future.

The country, however, wanted something smaller, more intricate and somehow grander. A wristwatch. It was an unlikely brief. To ask a company that built machines for factories to build a machine for the wrist. Then again, post-independence India had made a quiet art of making do, of chasing the improbable with tools fashioned from necessity.

HMT first knocked on Seiko’s door, but Japan’s most punctual watchmaker politely declined. The proposal then crossed Osaka to a neighbour, Citizen, who agreed to collaborate. The partnership turned out to be as philosophical as it was technical. Japan supplied precision and method. India provided the ingenuity to make it affordable for the everyday man.

The first HMT watch was assembled in 1962 at the new Bangalore plant. When the inaugural piece was presented to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, he did not treat it as a ceremonial token. He slipped it on. The model would later be called the Janata, meaning ‘the people,’ a fitting name for a watch that would come to define the wrist of a generation.

It was modest, mechanical and humble in its geometry. The dial was clean and unadorned, its numerals as practical as its purpose. It was not designed to dazzle but to endure. Over the following decades, millions like my father would wear it each day, then leave it on their nightstands for their children to gaze at and dream of owning one someday.

It was the time of small dreams. It was the time of HMT.

The Uniform of a Generation

The first watches from HMT were mostly assembled from imported parts, their movements licensed from Citizen, their gears whispering in a borrowed language. In less than a decade, though, the assembly line had turned into an ecosystem of self-reliance.

As India grew, so did its timekeeper. The Janata soon found company. The Pilot arrived as a small, black-dialled watch with a sky-adjacent myth. It was the watch for the man who saw himself as a quiet hero, even if his only fighter jet was the crowded 8:05 local. Then came the Sona, a slim, gold-plated wafer that gleamed from beneath crisp shirt cuffs. This was HMT in its formal attire, the watch that emerged from its velvet box for weddings and interviews.

There was the Jawan, Kanchan, Rajat, Sanjay and Kohinoor, each name a small performance of aspiration. In the India of yore, these watches were not bought, but earned. They became the standard-issue reward for an Indian life lived well. An HMT marked each milestone. You received one when you graduated from college, a ticket to the world of adult responsibility. You were gifted one at your wedding, a quiet wish for prosperous times. And after thirty years of loyal service, you were presented with a gold-plated Kanchan or Rajat, a heavy, automatic thank-you for a lifetime of hours.

By the 1980s, to look around a government office, a university classroom, or a train compartment was to see a sea of HMTs. The brand had become the nation’s unofficial uniform. Waiting lists sometimes stretched for months. There were even stories of weddings postponed until a ‘Sanjay’ could be secured for Sanjay.

HMT was no longer just a watchmaker. It had become a quiet institution, churning out two million watches a year across its various factories. They were the shared pulse that bound the country’s working hands together. Each tick was a small, collective affirmation that India was, at last, keeping its own time.

The Missed Beat

By the 1990s, though, the rhythm had begun to change. Liberalisation arrived like a new calendar, shiny, unpredictable and printed elsewhere. The old certainties of state planning gave way to the chaos of choice. And HMT, honest in its steel and stubborn in its sincerity, found itself out of sync. Its designs looked tired, its technology slower than the world it once helped to measure.

In a country that had long worn its watches as proof of arrival, HMT’s humility became its undoing. The same quiet dignity that once made it universal now made it invisible. It was a watch built for a nation of engineers and clerks, not for one discovering consumers and careers.

India had moved on to watches that no longer needed winding, and those that sparkled under showroom lights. HMT ticked on resolutely for a few more decades, but its seconds no longer belonged to the future.